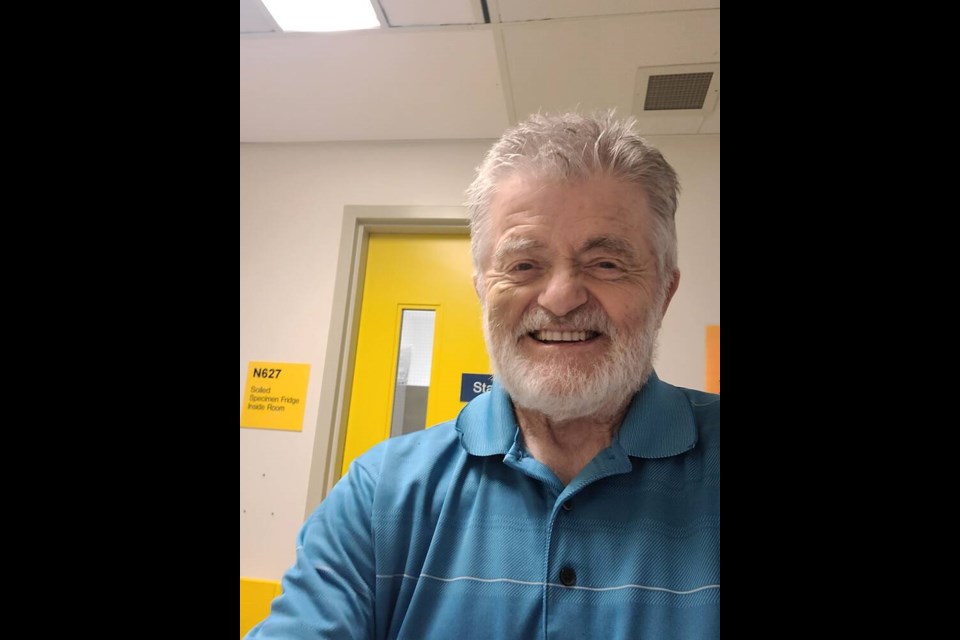

Saanich resident Eric Roberts was one of many seniors in Victoria General Hospital this month — the only difference being he spent nine of his 10 days there in hallways.

Roberts, a retiree-turned potter, was admitted to hospital on Feb. 24 for a series of infections and subsequent delirium. He was discharged on March 4.

“I was moved three times to different locations to accommodate bathroom accessibility for in-coming patients,” Roberts said.

For four days, he was parked by a garbage room. On another day, his food tray was moved seven times for hallway traffic. And for one blessed day he had a room with a TV and some privacy.

“I was in a lovely room one night and visitors came to see me and halfway through the next morning I was bounced out,” Roberts said. “I guess someone more deserving needed the room. Even though I had infections, I guess I was seen as healthy enough to withstand the hallway.”

Roberts said although “at 87, a few things have cropped up” he’s an otherwise active and healthy senior who lives independently.

Still, he said, trying to recuperate amid the “hustle and bustle” of hallways and 24-hour noise and lights was challenging.

The nursing care and the meals were generally good, he said, “the nurses were apologizing all the time” for his hallway location, and he got past the indignity of the lack of privacy.

“If you have quite a bit of pain, you don’t give a damn who sees what and who does what,” Roberts said. “I was in that situation quite a bit. Most guys, after a while, don’t care — but there was really no screen around me ever.”

A statement from Island Health said it cannot speak to specific patient details. In general, hospitals all across the Island and province “are incredibly busy and capacity issues are an ongoing challenge,” it said, but patients are never turned away.

“When our sites are extremely busy, at times, some patients are being cared for in temporary places, including hallways,” the statement said. “We know this is not ideal, and we apologize.”

Island Health statistics show Victoria General Hospital’s occupancy rate so far this fiscal year is 103.9 per cent — slightly higher than last year’s 102.4 per cent but below the 106.4 per cent seen in 2018-2019.

Occupancy above 100 per cent does not necessarily mean patients are in hallways, as it can include people in the emergency department waiting for an inpatient bed and patients on wards in over-census beds (above base-bed occupancy), according to Island Health.

Island Heath said “hallway medicine” is usually temporary while patients await transition to a unit or room “and we ensure the delivery of appropriate care and appropriate staffing levels.”

Roberts believes part of the solution is moving out seniors who are waiting for residential care or home care.

He said he saw at least two people on his floor who seemed to need long-term care and described nurses having to redirect wandering patients back to their rooms or put them in wheelchairs with food trays to secure them.

As of March 12, Victoria General Hospital’s rate of alternative-level-care patients — those who no longer require hospital care but are waiting to go back in their home with supports or to assisted living or long-term care — was 11.7 per cent, said Island Health.

B.C. seniors advocate Isobel Mackenzie, in her annual Monitoring Seniors Services report, released last week, noted that the oldest baby boomers are turning 78 this year and while most will live well and independently into their 80s, health-care demands spike after age 85.

The bulk of the population is going to enter that cohort over the next 10 years, said Mackenzie. “I think that governments have to recognize that, and the public has to recognize that, as we plan for the future.”

Mackenzie said another challenge is the cost of home-support services, which are about $9,000 a year based on a $29,000 annual income. B.C. is one of just a few provinces to charge for home support and is the most expensive of those that do.

Mackenzie argues a lack of affordable home supports and community supports such as adult day programs drives seniors and their caregivers toward long-term care, driving up demand and increasing wait-times.

There are about 29,430 publicly subsidized long-term care beds at 297 sites in B.C.

While the overall number of publicly subsidized sites and beds has increased by three per cent over five years, the number of beds per 1,000 people age 75 and older decreased 12 per cent during the same time period due to population growth.

Last year, there were 5,175 clients waiting for a publicly subsidized long-term care bed, with an average wait-time of just over 200 days.

Mackenzie’s report shows that patients in the province are admitted four times faster if they make a hospital visit — something she says might “incentivize” people to go to hospital in order to get placed in long-term care.