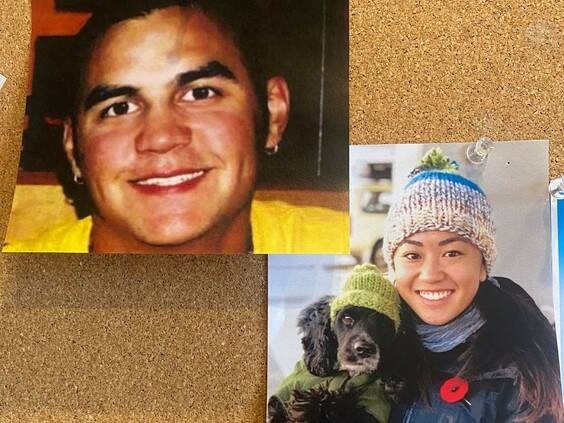

Photos of Todd Marr and Vancouver Police Const. Nicole Chan are pinned to the bulletin board in the Victoria office of Elenore Sturko, the B.C. Liberal mental health and addictions critic.

“You can see up on my board I have two photos,” the Surrey South MLA said, pointing to the snapshots of Marr and Chan, both shown smiling. “Because I’m working for people like them.”

They died by suicide, 10 years apart. They both died the day after they were discharged from hospital. That’s happening far too often in B.C., Sturko said, which is why on Wednesday she will introduce a private member’s bill that would require hospital staff to seek more information from the relatives or care providers before deciding whether a person should be involuntarily detained under the Mental Health Act.

The bill would amend Section 28 of the Mental Health Act to require doctors and nurse practitioners to make “reasonable attempts” to contact the family or care providers of a person brought to hospital by police because they are believed to be a danger to themself or others.

“It gives doctors and nurse practitioners an additional tool in order to make an assessment on someone they perhaps only met five minutes before in the emergency room,” said Sturko, who retired from the Surrey RCMP last year after she was elected to represent Surrey South. “We’re asking someone to make a very critical diagnosis or determination with potentially limited information.”

The bill is backed by the families of Marr and Chan, the 30-year-old Vancouver police officer who died by suicide in 2019 following two inappropriate sexual relationships with two superior officers.

It’s also deeply personal for Sturko, one of the Langley RCMP officers who responded shortly after Marr jumped to his death from an overpass on Sept. 9, 2009. The day before, his mother, Lorraine Marr, took the 32-year-old stonemason to Langley Memorial Hospital hoping he could get a psychiatric assessment for his suicidal thoughts.

“They talked to him, they didn’t talk to me,” Lorraine Marr said from her Langley home alongside her husband, Chuck Marr. “I wish I would have had that opportunity.”

She would have told hospital staff that Marr, a former star athlete who was addicted to crystal meth, tried to take his own life the previous day.

“They told him that they couldn’t do anything for him except they could put him in a padded room and the next morning they would give him a bus ticket and send him on his way,” she said, her voice cracking. “You feel like you’re at a dead end. And he definitely felt he was at a dead end. He just felt like there was no more help.”

Last month, Sturko opened up about her struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder stemming from Marr’s death.

The day after being turned away from hospital, Marr asked his mother to drive him to McDonald’s for a burger. Suddenly, he asked her to stop the car. He told her he loved his family before running toward the highway overpass.

Sturko was haunted by the cries of his mother and, for years, felt flashes of anger at the medical system for not holding Marr involuntarily. Sturko, a married mother of three, turned to alcohol before she sought counselling for her PTSD.

Lorraine and Chuck Marr reached out to Sturko after they read her story and invited her to their Langley home on Friday.

Lorraine Marr said hearing about how much her son’s case affected Sturko brought back a “flood of emotions.”

Marr’s parents and Chan’s sister, Jenn Chan, will appear with Sturko Wednesday in Victoria at a news conference about the private member’s bill.

A coroner’s inquest heard that the night before Chan died by suicide, a police psychologist passed along urgent information about her previous suicide attempts to staff at Vancouver General Hospital where she was being held involuntarily.

Despite this, Chan was discharged. The 30-year-old died by suicide on Jan. 27, 2019.

Dr. Randy Mackoff, police psychologist with knowledge of Chan’s past suicide attempts, testified at the coroner’s inquest that in his experience, hospital staff will rarely speak to the relatives or care providers of people brought to hospital under the Mental Health Act, which means they often lack important context about the patient’s past behaviour.

The jury in the coroner’s inquest made 12 recommendations, including better communication between community health providers, police and paramedics and the hospital physician treating the person in mental health crisis.

Jenn Chan said she wishes hospital staff reached out to her before Chan was discharged, so she could provide the full picture on her previous suicide attempts and mental health history.

Even knowing her sister was being released would have allowed family to check in on her, she said.

Jenn Chan believes the private member’s bill “adds an extra layer to preventing a patient from being released prematurely” and hopes it will pass “to prevent deaths and other families from having to experience the loss of their loved ones.”

Private member’s bills rarely pass, but Sturko hopes this one will be the exception, because she believes it will save lives.

Todd Marr’s parents agree. “I hope it doesn’t get caught in all the politicking,” his father said.