University of Victoria students are making their imprint on space research by designing and building a miniature satellite, known as a CubeSat, to go into the cosmos.

The team is part of the Canadian CubeSat Project, started in 2017, and spent time putting the finishing touches on its creation at Canadian Space Agency headquarters in Longueuil, Que.

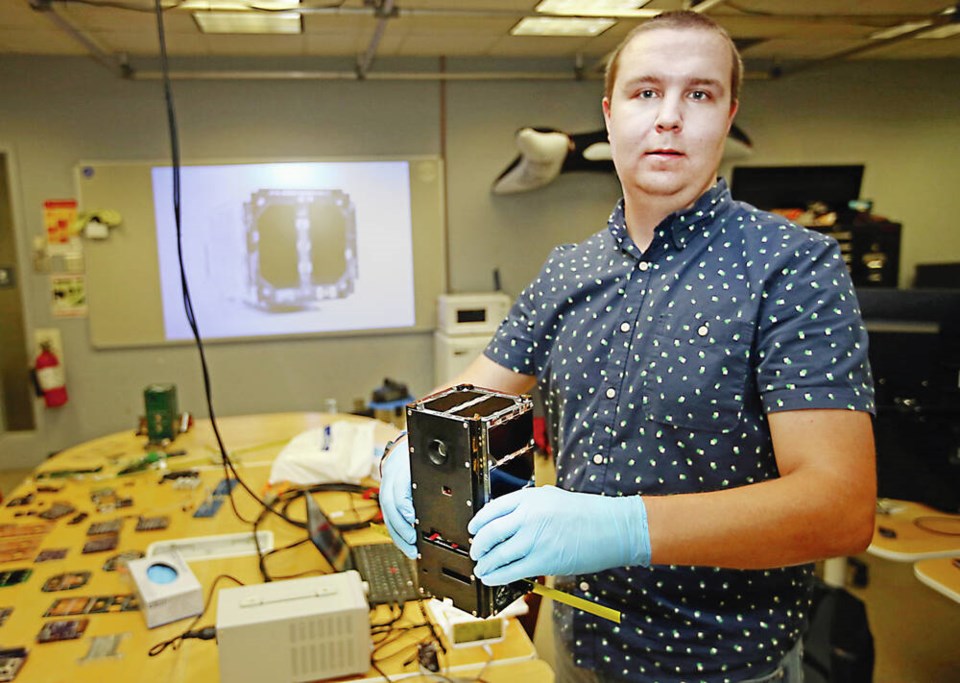

UVic team member Alex Doknjas, a 27-year-old electrical-engineering graduate, said there are about five full-time people preparing for an October launch of the device they are calling ORCASat — short for Optical Reference Calibration Satellite.

“Also it’s built in B.C. and B.C. is known for orcas, that’s kind of the play there.”

The CubeSat will be packaged in a rocket that’s launched from Florida’s Kennedy Space Center and goes to the International Space Station, which sits at a height of 400 kilometres. There, it’s sent into space via a spring-loaded device and remains aloft for up to 18 months collecting data that’s monitored and analyzed by the university team.

When the CubeSat returns to Earth, it will burn up on re-entry.

The space agency selected 15 universities for grants of up to $250,000 for the nationwide effort. UVic is leading one of the initiatives in co-operation with students from the University of B.C. and Simon Fraser University, and has previously earned top prizes for its entries at the Canadian Satellite Design Challenge.

The main structure of CubeSats is fashioned from aluminum and they are typically 10-by-10-by-10 centimetres, or about the size of a Rubik’s cube, weigh about a kilogram and can be used alone or in groups of up to 24. But the UVic device has a slightly different design and is a touch bigger than the norm — approximately the size of a two-litre milk carton.

The advent of smaller components has made compact satellites efficient, and provide a cheaper option to build and launch.

“It’s amazing what you can do now with the advancements of technology,” said Tony Pellerin, manager of the mechanical-engineering group at the Canadian Space Agency.

In the early 1990s, a typical satellite weighed a tonne. The size eventually dropped to 250 to 500 kilograms, since weight is the prime expense of sending satellites into space. Some weigh less now.

CubeSats were developed with students in mind, but businesses also use the devices for their own missions, Pellerin said.

Despite their size, CubeSats have uses ranging from carrying new cameras to test their reliability to conducting experiments, like gathering information on magnetic fields to assess their use in earthquake detection.

Plans for the CubeSats that are part of the student project include monitoring the Prince Edward Island potato crop to get a better idea of when to plant.

Dalhousie University’s satellite will be launched in October, as well, with the other 13 set to go in early January.

Work began on ORCASat in September 2018, with UVic taking on the added challenge of building everything themselves, Doknjas said. The pandemic affected the original schedule, which called for completion in two years.

“Ninety per cent of the spacecraft is designed, assembled, tested here in Victoria, and we use a lot of local manufacturing to help us out, as well,” Doknjas said.

Another UVic team member, 25-year-old fourth-year electrical-and-computer engineering student Stefan Bichlmaier, said he joined the project just as he was starting his degree.

“Right at the beginning I didn’t really understand the whole engineering process. I didn’t even know it was possible to be part of a project that could go into space.

“Putting something into space does require a lot of certainty into what you’re designing, so being part of that was a good jump start into becoming an engineer.”

Pellerin said their satellite has basic elements such as a power system made up of solar panels and batteries, a computer and a radio system for communication with the device.

He said the “science objective” for UVic is to have a satellite that functions as an “artificial star” — with a laser as its light source.

Like real stars, ORCASat emits light and is visible with a telescope, he said, although ORCASat will appear red rather than yellow.

While looking at stars, you only know how bright they appear to you, not how bright they actually are, Doknjas said. But since the ORCASat is equipped to measure its own brightness, the UVic team has two values to compare.

“They want to correct for the atmospheric effect on the light,” Pellerin said. “They can transfer this information to astronomers, who can actually use that information to fine-tune their images when they look at stars.”

Bichlmaier likened the experiment to taking away the “twinkling” effect, caused by the atmosphere, from stars that are observed from Earth.

The goal of the project is to give professors at post-secondary institutions a chance to introduce students to an actual space mission, with space agency experts available to guide the teams.

About 510 CubeSats from 50 countries have been deployed since the first one went into space in 2003. The standard size for the CubeSat was established in 1999 by professors at California Polytechnic State University and Stanford University.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]