The 1994 XV Commonwealth Games was a moment when all of Greater Victoria, regardless of address or municipality, came together in a way some say might not happen today.

“I think co-operation was a little more usual back then,” said longtime Victoria Coun. Geoff Young. “There was more of a feeling of a single city than we have now.”

But from Aug. 18 to 28, 1994, Greater Victoria’s municipalities did manage something special.

When the call for volunteers went out, Games organizers crossed their fingers and hoped to attract 10,000. More than 13,000 came forward — including more than 20 people who agreed to dress up like the cartoon orca Klee Wyck, the Games mascot.

The Games were budgeted to cost $160 million split among federal, provincial and local governments. Not only did it come in on budget, there was $4.6 million left over. It was handed to Victoria sports programs.

From the start of planning, the District of Saanich leapt. It leveraged its money to build the $22-million Commonwealth Pool, with $16 million paid for by the Games.

The University of Victoria agreed to be home to the athletes village and scored 1,000 permanent spots of student housing, part of $11 million in campus improvements.

Even the West Shore managed to get $5 million for a bicycle velodrome and a lawn-bowling pitch, still ranked one of the world’s best, engineered to rest on tamped sand and laser surveyed to be level perfect.

John Ranns, Metchosin mayor and member of the Juan de Fuca Recreation Association, said lawn bowling may not attract hundreds now. But, he said, demographics shift, so he opposes attempts to use the greens for something else.

“People will say: ‘Let’s tear up the lawn bowling greens.’ I always say: ‘Are you kidding me? They’re world class,’ ” Ranns said.

Victoria, on the other hand, was left with no legacy facility when two attempts at a referendum, in 1989 and 1992, asking citizens to agree to a new arena failed. In the end, Victoria settled for a $650,000 makeover to Memorial Arena.

Then there was the strike that almost made a disaster of the Games for everybody.

Municipal workers, including those who collect trash, went on strike a month before the Games started. The city complained the timing wasn’t fair and refused to give in. Streets started to fill up with garbage.

It took a last-minute intervention from the provincial government to fix. Eight days before the Games opened, the province persuaded both sides to settle their dispute after the event. City workers immediately set to work cleaning up the streets.

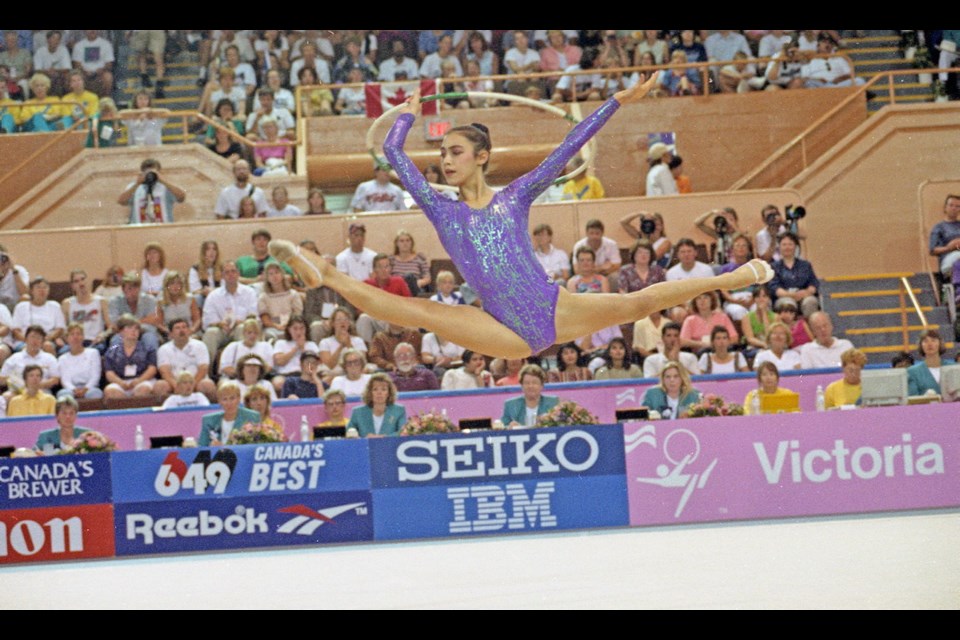

In the end, the games attracted 3,700 athletes from 64 different countries and in a few small ways, they made some history.

For example, for the first time since 1958 South Africa competed as a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. Its previous system of apartheid, white-minority rule, kept it excluded. But in 1994 Nelson Mandela himself requested his country be allowed to compete and a team was hastily cobbled together.

The South Africans even took two gold medals in lawn bowling. The winners broke down on the podium and the crowd cheered.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong, then administered by the U.K., competed internationally for the last time as its own entity. In 1997 Hong Kong reverted to Chinese control.

The Queen and Prince Philip opened the games and the ceremonies were led off by First Nations. Despite some grumbling by one local chief, many First Nations people later expressed huge pride at the chance to showcase their culture, including a canoe flotilla in the Inner Harbour to deliver the Games’ official baton.

And Victoria managed to live up to the reputation of the Commonwealth Games being “the Friendly Games.”

When a Malaysian official misplaced a bag with $7,500 in Canadian cash and $10,000 in traveller’s cheques, the bag and money were returned the next day.

The cash-strapped Sierra Leonean team of 12 arrived with little more than their suitcases, so Victorians bought them athletic gear. When the team’s surprise silver medal was withdrawn because the runner failed a dope test, the donors expressed no sense of betrayal, only empathy.

Saanich Coun. Colin Plant was only 22 and a third-year acting student at UVic when he took on the role of Klee Wyck.

Plant looks back now and remembers nothing but wonder and fun. The volunteer pass gave him access to the athletes village. He mingled with people from all over the world and everybody reacted with delight to Klee Wyck.

“It was such a blast to be part of such an event on that scale,” he said. “It was a different time.

“I don’t think we’ve had that same level of energy in the city ever since.”