You’ve been called to respond to a disturbance, and as you exit your patrol car, you see an obviously distraught person partially hidden behind a vehicle parked in front of a convenience store in a strip mall.

To your right, you see your partner, who is calmly talking to the individual, trying to de-escalate the situation.

Suddenly, the individual emerges from behind the vehicle with a knife in his hand, and advances on you.

As you pull the trigger of the conductive energy weapon — or Taser — in your hand, you have the choice of aiming at the torso, below the heart, or the legs.

You see the projectile barbs fly out and hit their target, sending 1,200 volts of electricity through the man’s body, and he goes down.

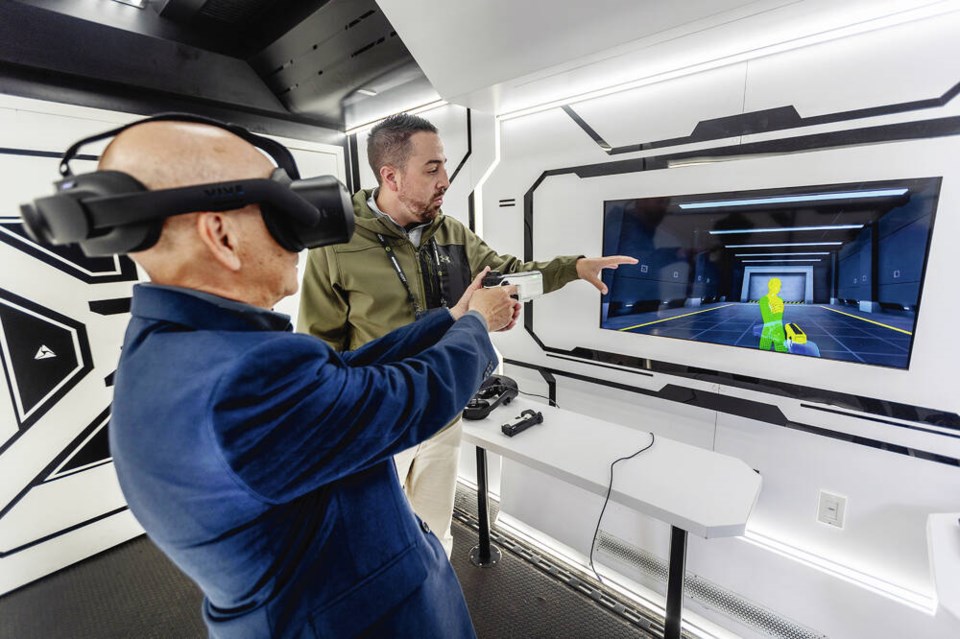

You know this is just a virtual-reality training scenario, but as you take off the headset, your hands are shaking and your heart is beating rapidly.

The VR sets were on display in Victoria this week in a parking lot adjacent to Victoria police headquarters on Caledonia Avenue, as Axon — a U.S.-based company that supplies law-enforcement agencies with everything from conductive energy weapons to body cameras and drones — showed off its wares to the media and members of the Victoria and Esquimalt Police Board.

The company was in Victoria as part of a road show to showcase its products to law enforcement in B.C. and Alberta, including Delta, Victoria and Calgary.

The convenience-store scenario is one of 26 police trainees can choose from, including modules with people who are experiencing a mental-health crisis or threatening suicide, or who have autism or schizophrenia.

But there is a twist: 16 of the simulation scenarios include “empathy” mode, which puts the police officer in the shoes of the person in crisis.

For the first few minutes of the empathy scenario, the officer becomes the person who is experiencing a mental-health crisis, or is hard of hearing, or who does not understand instructions in English.

“It is meant to give officers the sense of a person who is stressed-out even before police arrive,” said Vishal Dhir, senior vice president for the Americas for Axon.

“We need to remind ourselves that we are not meeting people on their best day.”

Dhir said others in the law-enforcement community, such as dispatchers, can also benefit from the empathy-training modules.

The virtual-reality training modules came out in 2020 and a number of law-enforcement agencies across Canada are using them, said Axon. In B.C. two agencies are currently running trials with the technology, said the company, which declined to name the agencies.

The Victoria Police Department says it’s studying the program as a possible addition to its current in-person officer training.

“There are several considerations, but we are interested and curious about the possibility of integrating VR into our reality-based training programs,” said Const. Terri Healy, spokesperson for the Victoria Police Department.

Dhir said the virtual reality equipment makes practice using a Taser more cost-effective for a police department. He noted that generally, officers only have the opportunity to discharge a Taser once a year during their annual user re-certification.

But the virtual reality training program is subscription-based and with police budgets under pressure, one academic wonders if there might be less-expensive and locally available alternatives.

“There is a tendency reflecting the idea that technology can fix anything,” said Dr. Michelle Bonner, a political science professor at the University of Victoria. “It’s fun and new, but it is usually expensive and does not make any difference in practice.”

She said more research is needed to craft a cost-benefit analysis on adopting new training programs, suggesting it can be more cost-effective to bring on a “whole array” of people who already work in the community with those with mental-health and other issues.

“The ideal is not to involve the police at all [in mental-health crisis situations],” said Bonner, adding empathy “isn’t something that you train for.”

“If you did not have it before, it would take you a while to change. For the training to be effective, a person has to be open to change — rather than a person just ticking a box to indicate that they have taken the training.”

Axon also showed off its software that uses artificial intelligence to help write police reports — a task the company argues can eat up 40 per cent of police officers’ time.

The company says the program can complete up to 90 per cent of the report, with the officer filling in the remaining 10 per cent and digitally signing the document ahead of submission to Crown counsel.

The software extrapolates audio and video data from body cameras, allows officers to take digital notes, allows the transfer of data and keeps track of evidence digitally, the company says. Audio recordings from interview rooms can also be transcribed, again with the help of artificial intelligence.

“Using a template, it can create a two-page report in 15 seconds, enabling officers to spend more time in the community,” said Dhir.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]