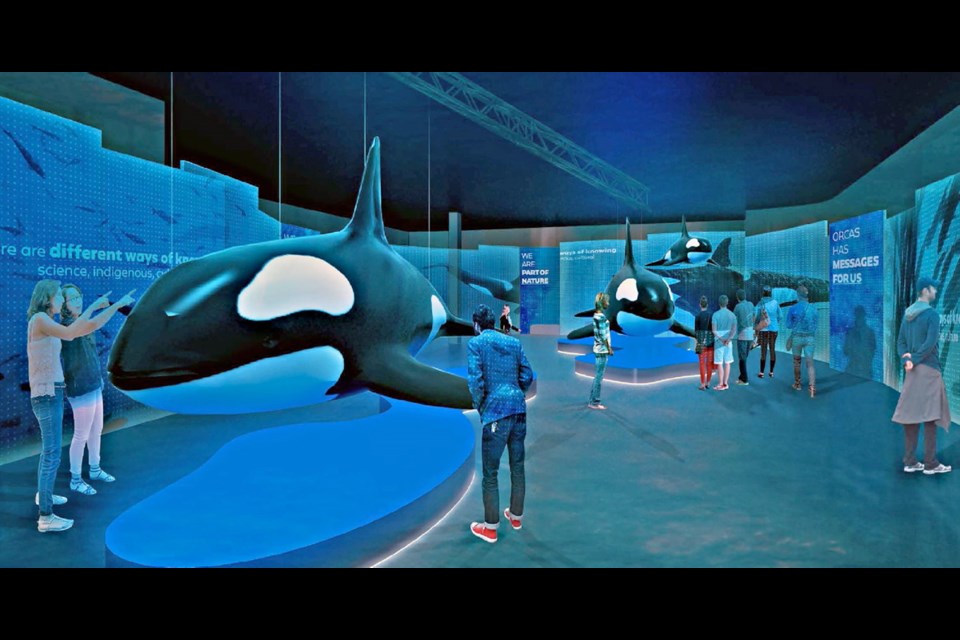

The massive centrepiece of an ambitious orca exhibit planned for the Royal B.C. Museum is intended to be both a show-stopper and a poignant message about the dire circumstances of the region’s southern resident orca population.

Three life-sized replica orcas will be part of a $1.6-million exhibit scheduled to open in mid-2020. The replicas will be modelled on three local orcas from J-pod — J1 Ruffles, a nine-metre long male; J16 Slick, a seven-metre female; and J50 Scarlet, a 3.5-metre juvenile.

Michael Barnes, head of exhibits for the museum, said the immense creatures that will dominate the exhibit were chosen for a reason — two of the three whales are now dead.

Slick, who is still alive, was mother to Scarlet, declared missing and presumed dead in the fall of 2018. The large male Ruffles died in 2011.

They were also members of the endangered southern resident orca population that now numbers an estimated 75 whales.

“The sad reality is they are dead and that will help drive the story,” Barnes said.

The museum issued a request for proposals in August for firms interested in creating the replicas by an April 2020 deadline.

The request for proposals closes Sept. 13.

The orca exhibit is expected to run at the museum between mid-May of 2020 and the end of next year, before touring North America and Europe for the following five years.

Barnes said the project, which has been more than two years in planning and is now getting into the design and production phase, might be the largest travelling exhibit the museum has created since Chiefly Feasts in 1992.

Chiefly Feasts, The Enduring Kwakwaka’wakw Potlatch, was a $160,000 travelling exhibit produced in partnership with the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Before it went on tour, it was seen by an estimated 500,000 people over six months at the Royal B.C. Museum.

“It’s been quite a few years since we’ve taken on an international traveller,” said Barnes, adding the goal of Orcas: Our Shared Future is both to get out the environmental message and raise awareness of the RBCM as a world-class museum with significant stories to tell.

Leah Best, head of knowledge for the RBCM, whose team has been developing the exhibit’s content over the last two years, said a piece of First Nations art — a large screen by artist Bill Reid that shows orcas deeply intertwined with other living things — embodies the message of the project: that we are part of nature, not apart from it.

“Even the title Orcas: Our Shared Future references the fact that the fate of the southern resident orcas is intertwined with our own fate,” she said.

Best said the story told in the exhibit is both intensely local and internationally relevant, and begins with a botched 1964 harpooning off Saturna Island, which resulted in an orca being captured for display and study for the first time.

The movement to protect whales also began here, with Greenpeace’s first save-the-whales demonstration off Vancouver’s Jericho Beach.

Best said the idea is to bring different lenses to the orca story, including a no-holds-barred study of the captivity chapter, along with Indigenous knowledge and understanding, scientific study of the animals and a call to action as orcas struggle to survive.

The hope is that audiences will leave inspired and engaged, instead of feeling like there’s nothing they can do, she said.

“Yeah, it’s dire, but we hope empathy is created by telling the stories of actual orcas of this area,” she said, adding there will be no mistaking one of the other messages: when it comes to orcas, we are the problem.

The content will be displayed in a variety of ways, including seven hands-on interactive units, 11 videos, text, images, artifacts, fossils and Indigenous art. There is also the massive immersive space in which the replica orcas will be placed, designed to give visitors the feeling of being in the orcas’ world.

A video toward the end of the exhibit will show orcas in their natural state, interacting with each other. “We are hoping that’s a better way to leave the visitor, [thinking] they can go and do something about it,” Best said.

Note to readers: This story has been corrected. The orca known as J16, or Slick, is still alive, and J1 was not the father of Scarlet. Incorrect information was provided to the Times Colonist.