Killer whales in the coastal waters of British Columbia are swimming against the current.

Affected by marine contaminants, overfishing and the incessant thrum of boat traffic, several populations of these ecologically critical apex predators now face uncertain futures. Particularly dire is the southern resident killer whale ecotype, whose declining headcount numbers just 73.

But a new lab in West Vancouver is using a bottom-up method to shed light on their cousins, the northern resident killer whales, in hopes of finding ways to avoid a similar fate.

While no one would consider research conducted at the site to be second rate, the lab in fact specializes in No. 2.

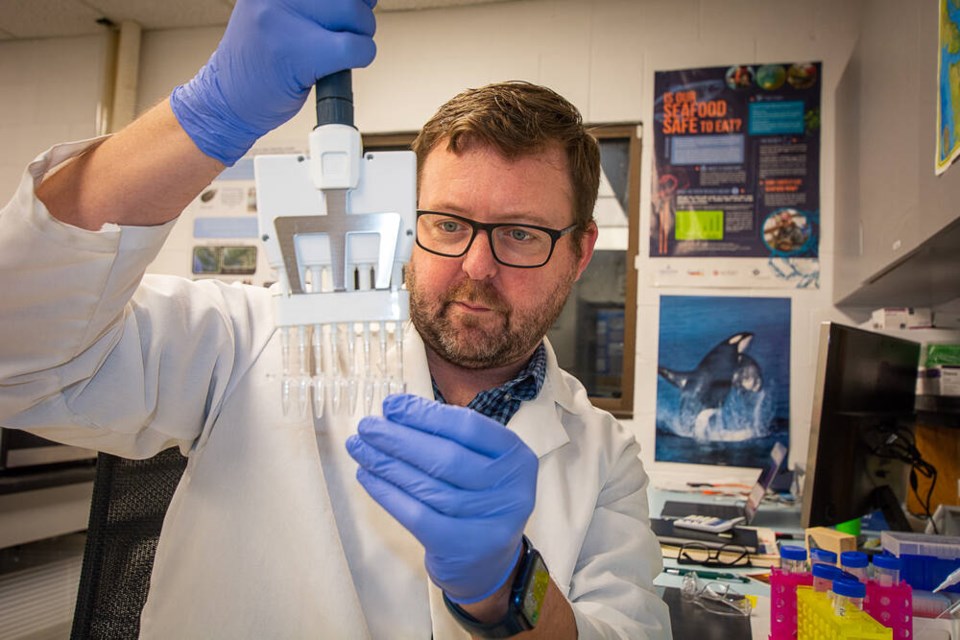

Near the centre of the maze-like collection of corridors and rooms that is the Pacific Science Enterprise Centre on Marine Drive, a fridge door is opened by Adam Warner of the Raincoast Conservation Foundation. Inside, racks of chilly shelves are stacked with vials. Some contain liquids – others are crowded with tangles of hair. All of them are whale poop.

But the excrement is just a means to an end. Inside the samples are DNA, from the predators themselves, and what they’ve been eating. With that information, Warner can determine where cetaceans and other coastal carnivores like wolves have been finding their meals, and help assess the group’s overall health.

Before the whale scat is dropped off at the lab, Raincoast scientists tail the cetaceans in boats to scoop their leavings.

On a genetic level, research from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has shown that the southern residents are highly inbred, and how that inbreeding is likely contributing to their continued decline.

Northern residents have been steadily adding numbers over the past 50 years, rising to 341 in 2022 from less than 125 in 1973. Part of Raincoast's research is to determine if northern residents have the same level of inbreeding.

“We looked at the northern resident killer whale populations – they’re also salmon eating – but they are actually doing pretty well,” Warner said.

A thin genetic pool is just one piece of the puzzle.

“There are all these other issues that they face like noise pollution,” he said. “They rely on echolocation for feeding … Even a small boat can make a lot of noise underwater.”

Despite pressures, other killer whale populations have been bouncing back in recent years too. Transient killer whales, also called Bigg’s killer whales, have been shown to be highly contaminated with pollutants, Warner explained, “which should be really bad.”

“But because their food source has become so abundant – a lot of seals, but then also some sea lions – they’ve actually been doing quite well,” he said.

“That’s a good example of, even though that’s really bad that they’re so heavily contaminated with these forever chemicals, if they have a lot of food, the population can still have a bit of a boom,” Warner added.

The hope is that, by taking action to boost the cetaceans’ food sources while reducing environmental stressors, populations can recover despite negatives like contamination and unfavourable genetics.

Extinction of killer whale populations would be devastating, researcher says

Policy decisions like the distancing of whale watching boats and restricting fishing in some areas have shown progress, Warner said.

“From the killer whale fecal work, if we can see that they’re feeding on a specific run of salmon, maybe there can be some regulations that would go into effect to provide a bit more of that, at least when they’re in the area, rather than heavily fishing it at the same time,” he added.

Warner points to government-supported projects that boost salmon populations, the primary menu item for resident killer whales. In 2022, Rainforest Conservation Foundation partnered with the Musqueam Indian Band to construct a breach of the North Arm Jetty of the Fraser River estuary.

“It really helps juvenile salmon get out into the estuary and get food early on,” Warner said.

After his current genetic research wraps up near the spring, Warner will work with his team to publish their findings, which will be presented to the Canadian and U.S. governments in hopes of driving policy changes.

If measures aren’t taken, and one day the top of the food chain is removed, the consequences would be widespread, Warner said.

“It’s hard to even think about how bad that would be,” he said. “Any time you get rid of an apex animal in an ecosystem, it really has a devastating effect on everything else there.”

The fallout from such a drastic change could also damage B.C.’s tourism industry, Warner said, which generates upwards of $13 billion in revenue for the province each year.

“We’re going to have to hope that it doesn’t get that bad,” he said.