B.C. Health Minister Adrian Dix empathized Wednesday with a Victoria teen with diabetes who feared for her life when her blood sugar dropped dangerously low and a B.C. Transit driver wouldn’t allow her to eat.

“I live that life,” said Dix, who also has type 1 diabetes. “I have a lot of sympathy for her. It’s a very difficult thing.”

Discovery School Grade 12 student Sequilla Stubbs, 17, was on a B.C. Transit bus on Jan. 9 heading home from school when her electronic glucose monitor started beeping. “I was really shaky, dizzy and seeing double,” said Sequilla. “I could possibly have a seizure.”

Sequilla’s type 1 diabetes, which can be exacerbated during the teen years, is referred to as particularly “brittle” — especially hard to manage.

On that day, her blood glucose level was below 2.2. Her ideal range is between 4 and 10.

A non-diabetic ideal range would be 4 to 6.

Sequilla, one of three people on the Route 10 bus headed toward Royal Jubilee Hospital, took out prepackaged mixed fruit from her lunch kit.

She barely took a bite when the driver told her to put the fruit away.

B.C. Transit spokesman Jonathon Dyck said the rule on buses is there is no eating or drinking on the bus to avoid spillage that could interrupt service, but that food and drink can be transported in closed containers.

Sequilla explained “multiple times” she was diabetic and crashing but the driver insisted she follow the rules.

“I put it away and sat on the bus and continued to go home and hoped I didn’t pass out,” said Sequilla. She bit the inside of her cheek to help keep herself awake.

“I was scared I’d be rushed off to the nearest hospital,” said Sequilla. “It has to be more accepted when someone says they have type 1 diabetes and they need to eat, otherwise it’s a life or death situation.”

Dyck said there are exceptions and flexibility within the rules for urgent medical reasons but that people are encouraged to plan ahead as much as is possible. Sequilla said the driver told her she should have arrived at the bus stop earlier.

The situation was not unusual for Sequilla: “There’s some days when I’m perfectly normal and then all of a sudden I drop rapidly and I can’t control it.”

Mother Jennifer Stubbs said her daughter has been riding the bus independently since Grade 7. “We’ve never had this issue before.”

“I’m frankly shocked,” said Stubbs. “I’m very disappointed. It makes me very nervous for everyone. Type 1 diabetes is not the only invisible disease that requires food or drink as a medical treatment option.”

Dyck noted that B.C. Transit has received a complaint. “We do apologize to the family for this situation,” said Dyck. “We expect all our drivers and staff to be professional and courteous at all times.”

Stubbs said she is “disgusted” by the half-hearted response from B.C. Transit.

“Frankly, this is a life or death situation,” said Stubbs.

Stubbs said she would like her daughter to receive a personal apology and that B.C. Transit should conduct awareness training about diabetes.

When Sequilla was six months old she was diagnosed with a growth disorder. It abnormally accelerated her development, both hormonally and physically. At age 2, Sequilla’s type 1 diabetes was diagnosed only after she slipped into a severe diabetic coma that resulted in brain swelling and learning disabilities.

“It’s been an uphill battle to get everything under control,” said Stubbs.

Stubbs said her daughter has worked very hard to be independent.

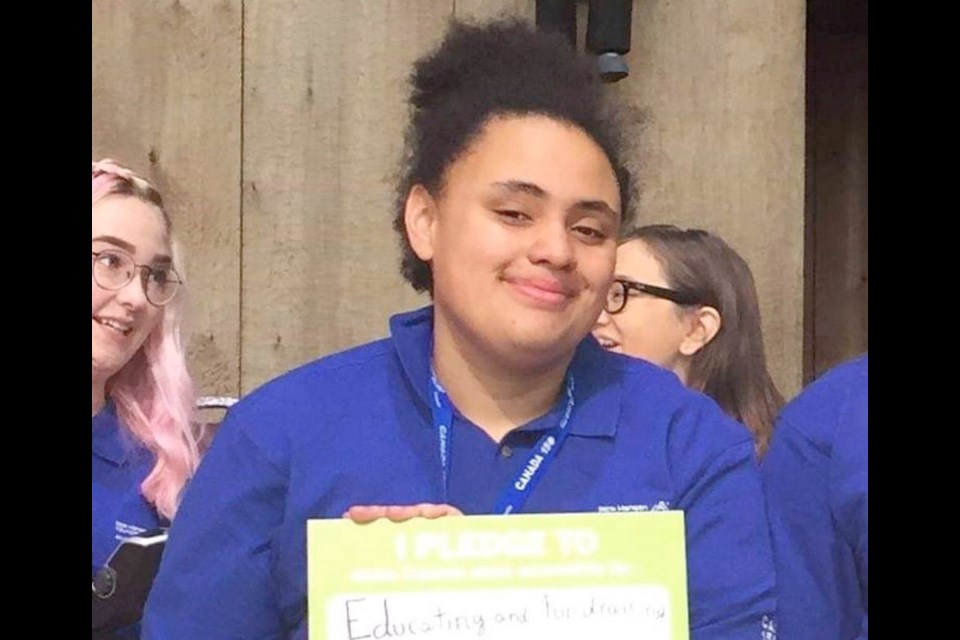

In 2017, Sequilla was selected by the Rick Hansen Foundation as one of 50 youth across Canada to attend a youth leadership summit in Ottawa. There she pledged to spread awareness about diabetes.

Living with type 1 diabetes is hard, said Sequilla, comparing it to a roller-coaster ride she never chose to board.

“It isn’t a joke and it’s not from eating too much candy,” said Sequilla.

“It’s not something I can control but I have to deal with it.”

Sequilla said she has educated people about diabetes since she was in kindergarten and she would be happy to train transit staff.