Father Charles Brandt, a hermit Catholic priest who lived a simple life connected to nature and set an unwavering spiritual example of environmentalism in a modern world for nearly five decades, has died.

Brandt was 97 and had been in North Island Hospital in the Comox Valley with pneumonia at the time of his death on Oct. 25.

“His stature as a spiritual teacher as well as his whole legendary reputation as someone who integrated spirituality with ecology will live on after him in the lives and efforts of the many people he directly inspired,” said Bruce Witzel, a close friend for decades.

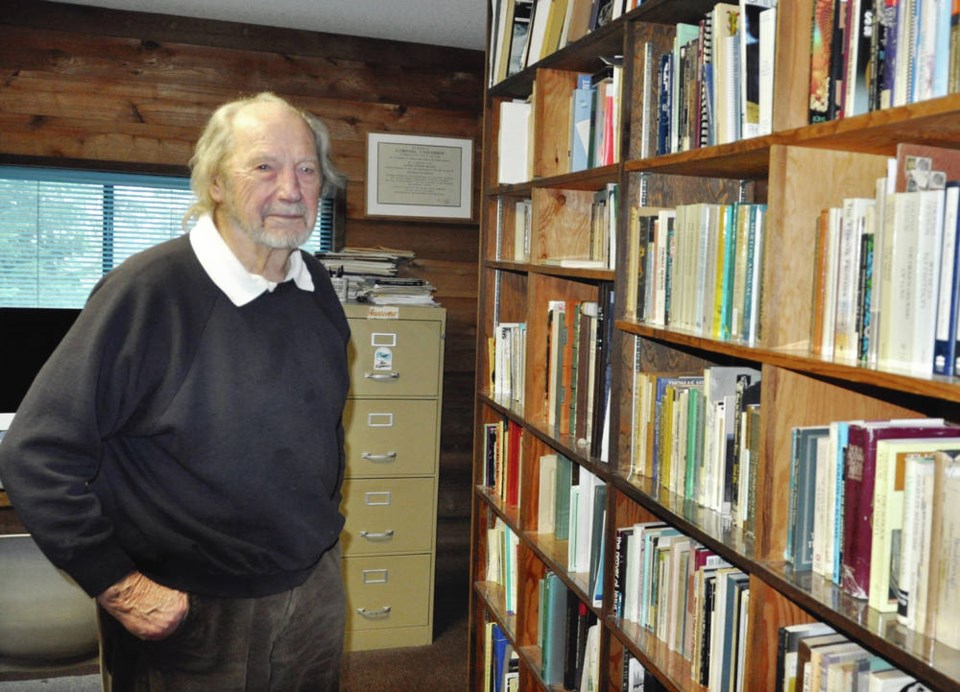

Brandt had lived a rustic life in a modest cedar hermitage on 30 acres along the Oyster River since 1965, where he preserved old books and taught Christian meditation and the importance of living in harmony with nature. He was the last surviving member of a unique hermit community established in 1964 near the Tsolum River and was ordained by Bishop Remi De Roo in 1966 as the first hermit priest in two centuries in the Roman Catholic Church.

In September, the Canadian Museum of Nature honoured Brandt with its lifetime achievement award for his decades of environmental stewardship, including spearheading a campaign to clean up the Tsolum River, which had been declared dead due to pollution from an abandoned copper mine that operated briefly in the 1960s on the north side of Mount Washington.

Brandt pressured provincial and local politicians to clean up the mine and inspired locals to help him restore the salmon-bearing Tsolum, which went from producing a handful of fish in 1983 to counts of more than 100,000 today.

He continued lending his wisdom and assistance to preserving the Oyster River and other environmental causes involving the surrounding forests, streams and ocean.

Bruce Wood, a retired physician and executor of Brandt’s estate, said he sat on the hermitage porch with Brandt a week before he died, sharing conversations about the Oyster River and surrounding area.

“He was in good spirits,” said Wood, but added that, at 97, likely knew his time was near.

Wood got to know Brandt in the early 1980s as part of the Friends of Strathcona Park, an environmental group that protested against the province’s plan to carve out chunks of the park for mining and logging.

“We got involved to fight that over three years. Some of us got arrested. Charles was always supportive of what we were doing.

“He was a true environmentalist.”

Journalist Mark Hume called Brandt’s death “a great loss to the planet.” Hume said in a memorial note he has a chapter about Brandt in a new book he’s writing, and when he called Brandt with questions last year “he responded with thoughtful, kind, wise and directional observations. “Truly one of a kind. Those of us who were lucky enough to know him, however briefly, were blessed.”

Added Hume: “The waters flow on, but the river is diminished.”

Witzel got to know Brandt first through his father, Mac, who welcomed and assisted Brandt when he first moved into the valley. Witzel, now 65, made a deeper, personal connection with the hermit priest starting at the age of 25 when he attended spiritual retreats.

Brandt’s connection with spirituality and ecology resonated with Witzel.

“He had a simple, but profound theme — only when we love something can we save it, and the only thing that really lasts is love.”

Witzel said one of Brandt’s sayings was “follow your bliss,” and he took that advice in the late 1980s by quitting a well-paying job at the Port Alice pulp mill where he was reasonably happy to pursue a mission building homes for the poor in Mexico. He ended up learning from Mexican craftsmen and returned home to train in carpentry and built a successful career.

Whenever there were difficult times, Witzel said his wife would say “go see Charles.”

“He always listened … he was a great gift,” said Witzel.

“His death will be a great loss at many people, but at the same time it’s not a loss because he’s within our hearts,” said Witzel. “He inspired people to continue in the direction we need to go for ourselves and the Earth.”

Wood said Brandt made his wishes known last year to give most of his land along the Oyster River to the Comox Valley Regional District for a park. A small piece of about 3.5 acres where the hermitage is located will be reserved for an active contemplative person of prayer who has concerns for the environment.

Before his life of solitude, the Kansas City-born Brandt was a navigator in the U.S. air force during the Second World War. He wen on to earn a degree in ornithology at Cornell University and a bachelor of divinity from Nashotah House, a seminary in Wisconsin.

Brandt published Meditations From the Wilderness and Self and the Environment.

He is survived by his sister-in-law, Wanda Brandt, and numerous nephews, nieces and their children and grandchildren in the United States. He was predeceased by his parents, Anna (nee Bridges) and Alvin Brandt, brothers Frank and Chet, and sisters Frances, Mary and Ella.

A funeral service officiated by Bishop Gary Gordon, Diocese of Victoria, and attended by retired bishop De Roo was held Friday at St. Patrick’s church in Campbell River with a limited seating of 50 due to pandemic protocols. The service was also live streamed to the basement where additional mourners could attend.

Donations in remembrance of Charles can be made to St. Andrews Cathedral in Victoria, the Tsolum River Restoration Society, Comox Valley Nature Society, Oyster River Enhancement Society or the Brandt Oyster River Hermitage Society.