Three months ago, Victoria police Staff Sgt. Conor King warned that the COVID-19 pandemic would worsen the opioid crisis and drive up drug-overdose deaths. His counterparts in Vancouver sounded the same alarm. The prediction proved true.

“It looked grim and it is grim,” said King, an illicit-drug expert and 22-year veteran of drug enforcement in B.C. “To see 170 deaths in May is really taking a giant leap backward in the efforts to grip this overdose crisis.”

Those 170 deaths represented the highest number of illicit-drug-overdose deaths in a single month in B.C. — almost twice as many as in May 2019. It was the equivalent of 5.5 overdose deaths per day in the province.

Although the pandemic has closed the Canada-U.S. border to most traffic, organized crime is still smuggling drugs across the border in transport trucks, said King. Illicit drugs are also arriving on cargo ships from overseas.

On May 9, Canadian border agents seized 60 kilograms of cocaine after stopping a truck at the Peace Arch border crossing.

But for every seizure at the border, many more go undetected, King said. “The border isn’t closed to drug dealers. It’s a porous border and drugs are coming in, including fentanyl.”

Police also have some information, as yet unverified, that organized-crime groups are importing the components to make fentanyl locally.

Whatever the source, there is no shortage of fentanyl on the streets, said King. “The street price of fentanyl has not changed in any meaningful way. When the price changes, that’s when we know there is a difference or a change in the supply, which affects the demand. We’re not seeing that here. We’re seeing the price is very stable.”

In Victoria, a 100-milligram dose of a substance that contains an unknown quantity of fentanyl sells for between $20 and $25, he said.

The B.C. Coroners Service has reported that post-mortem examinations have found extreme fentanyl concentrations in those who die of overdoses. In April and May, about 19 per cent of drug-death cases involved extreme fentanyl concentrations, compared with nine per cent between January 2019 and March 2020.

That leads police to believe there is a more toxic supply of fentanyl on the street, said King, although that hasn’t yet been confirmed by Health Canada’s drug analysis laboratory, which tests drugs police have seized.

Fentanyl used to be found only in opioids such as heroin. Today, police are seeing it in stimulant drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine. Sometimes, it’s added to the stimulant drugs on purpose. Other times, it’s a case of cross-contamination, said King

“Organized-crime groups don’t take any care, whatsoever, to make sure that the packaging of their fentanyl never touches the packaging of their methamphetamine. The mixing and packaging can take place in all the same containers, so you end up with methamphetamine that contains fentanyl and it makes for a very dangerous combination.”

Fentanyl is still being mailed from China, but that’s not the principal way it’s arriving, said King, who notes that importation has diversified.

“Drug traffickers learn from their mistakes and they evolve and they exploit any route available to them to import drugs into North America.”

For example, fentanyl is often mailed to European countries, then forwarded to cities on the east coast of North America and transported westward by land, he said.

King also attributes much of the increase in overdose deaths to the fact that many more people are using alone because of the pandemic.

“And that’s really, really important, even more important than the toxicity of the drugs,” he said.

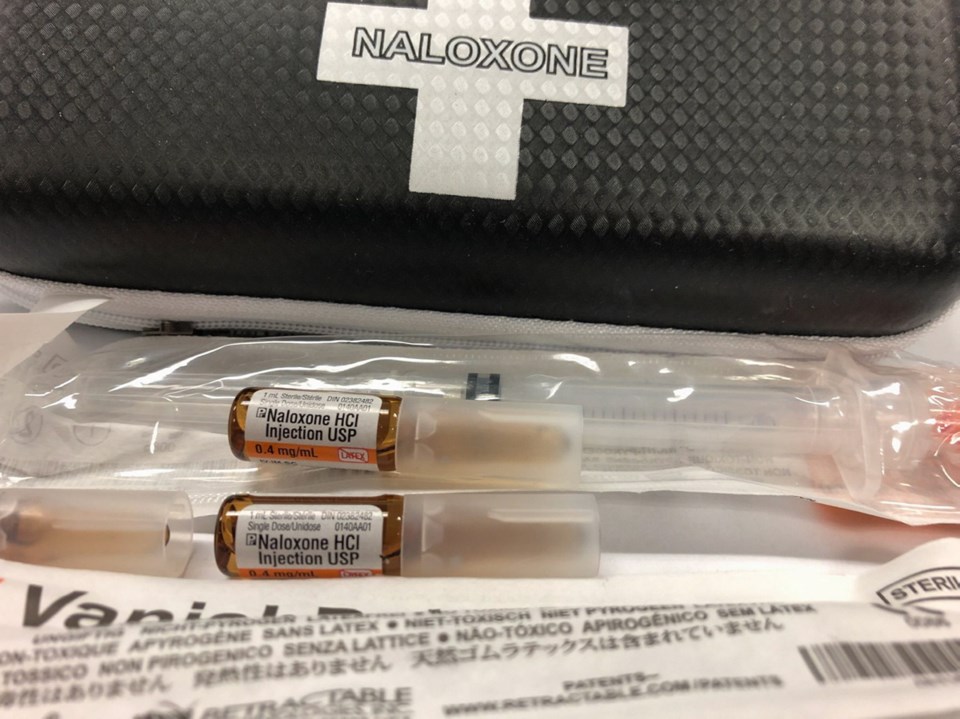

“Because even if a drug is really toxic, like fentanyl and carfentanil, but somebody is close by, there’s a really good chance that overdose can be reversed almost immediately with naloxone and rescue breathing. But you can’t reverse an unwitnessed overdose.”

Only a small number of this year’s 554 fatal overdoses took place in parks or on the street, King said. The vast majority of people died inside private residences.

“So many of the 170 people who died in May were not street-entrenched or marginalized people. They were blue-collar and white-collar workers dying at home,” said King. “They are people with an opioid-use disorder, but now they are using without any friends or family around.”

Eighty per cent of those who die from an illicit-drug overdose are men. Men are more likely to develop an addiction to pain killers. They are also more willing to take risks and use alone, said King.

People who want illicit drugs will call a dial-a-doper, who sometimes deliver drugs right to the front door. Or they’ll meet in a parking lot at a local mall or in a school yard on Saturday when no one is around, said King.

Those who don’t have connections will simply head downtown to buy drugs off the street.

“You see this with people who are from out of town who want to buy heroin or cocaine. They’ll find the homeless shelters and they’ll know that in that area, they’ll find drug dealers,” said King.

“This last week, we had people from out of town staying in hotel rooms and they bought drugs and it killed them.”

King is encouraged by the fact that harm-reduction measures such as safe-consumption sites and naloxone have saved thousands of lives.

He is hopeful that B.C.’s decision to allow physicians and nursing practitioners to prescribe a safe supply of alternative medication to illicit-drug users will save thousands more.

“This is where society will say: ‘These are our community members. We want change and we want something very, very significant done to change this. These are our dads and our brothers and our sons,’ ” said King.