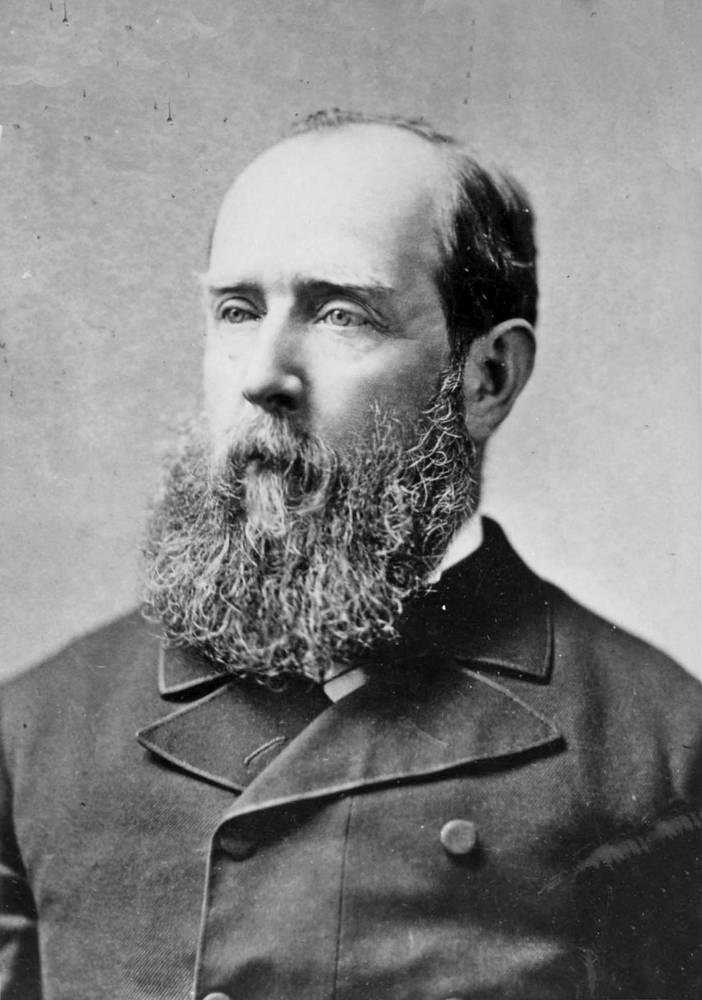

Joseph Trutch was an odious man.

He was racist not only in word but in action. As B.C.’s pre-Confederation land commissioner, he was contemptuous of Indigenous people, used abhorrent language when writing about them, ignored treaties and drastically reduced the size of reserves.

He was also the province’s first lieutenant-governor.

The question now is: Should his name be yanked off a street sign in Fairfield?

And, more broadly, what about the practice of yanking names in general, whether from street signs or buildings or cities or mountains?

We have been down this road (as it were) before. Three years ago, Victoria council discussed Trutch Street but did not change the name in the same way that UVic had done with a student residence bearing the Trutch name.

Now the matter is coming up again. Both Vancouver and Victoria city councils will look at renaming their respective Trutch Streets. In the capital’s case, it would affect a two-block road lined, mostly, by stately single-family homes.

At the same time, other communities are focusing on Prime Minister John A. Macdonald and his role in the creation of Canada’s residential school system. The University of Windsor announced Friday that it would rename its Macdonald Hall. The city council in Charlottetown — the birthplace of Confederation — this week had a statue of Canada’s first prime minister hauled away. Been there, done that, says Victoria, where the removal of a city hall statue in 2018 caused an uproar that has never completely subsided.

Name changes driven by shifting historical perspectives are nothing new. Here on the Island, Transportation Ministry signmakers in the Comox Valley must be tired of the tug-of-war between B.C.’s New Democrats and Liberals, who have taken turns erecting, then taking down, then re-erecting Ginger Goodwin Way markers along a section of highway dedicated to the early 20th-century labour martyr. (Speaking of perspective: In 2019, after I bemoaned an act of graveyard vandalism in which the hammer and sickle was chipped out of Goodwin’s headstone, I was taken to task by someone who had lost family in the Stalinist purges and who argued that the symbol is as offensive as the Nazi swastika.)

Hindsight changes views. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had the name of Hector-Louis Langevin, another Father of Confederation and another architect of the residential school system, taken off a building across from Parliament Hill in 2017.

Ten years before that, the name of Howard Green, a cabinet minister synonymous with the expulsion of Japanese-Canadians in the Second World War, disappeared from a Vancouver federal building despite his family’s strenuous denial of racism charges.

Such opposition is not uncommon: In 2019, when New Westminster removed a statue of Matthew Begbie, the judge who presided over the 1864 trial at which five Tsilhqot’in chiefs were sentenced to hang, critics argued the gesture was the result of oversimplifying both the man and the story.

That’s often the accusation, that 21st-century judgments of 19th-century characters like Begbie and Macdonald tend to be one-dimensional and lacking in context.

This week Alberta Premier Jason Kenney, responding to the decision to drop the Langevin name from a Calgary school, argued that if leaders of the past are to be judged harshly for taking positions that history proved to be wrong, then the likes of Tommy Douglas, who was deemed the Greatest Canadian by CBC viewers in 2004, but who as a young man was an enthusiastic support of eugenics, would be vulnerable to cancel culture, too. The same would apply to another onetime proponent of eugenics, Nellie McClung, the suffragette whose name is on the side of a Saanich library.

Sometimes it’s not just about who these figures were as people, but about what they represent. Few would argue Macdonald was a saint. He had to resign over the Pacific Scandal, and was a notorious drinker. (He is said to have told D’Arcy McGee: “Look here, McGee, this government can’t afford two drunkards, and you’ve got to stop.”) But as our first prime minister, he is often seen as synonymous with the country itself, meaning that while to some his statue is a symbol of the sins of colonialism, to others it represents all that is good about Canada.

Trutch, on the other hand, represents nothing good at all. As UVic professor Reuben Rose-Redwood wrote in a letter to Victoria council, Trutch was someone “whose racist views were extreme even for his own time.” Rose-Redwood quoted former lieutenant-governor Iona Campagnolo as speaking of the “stain” that Trutch left on the province’s history. What argument can be made for continuing to honour such a person? What signal would that send?

A motion before council June 10 would ask staff to report on the idea of renaming the road Truth Street, covering residents’ associated costs. Input from residents, First Nations and the Fairfield Gonzales Community Association would be solicited.