At least four dead owls have been discovered in North Saanich since July, possibly the result of eating poisoned rats.

Natasha Illi said she found two on Aug. 17 along Wilson Road while walking her dog. She didn’t know what to do with the owls, so she called conservation officers. One told her they were probably hit by vehicles, while the other was sympathetic, but too busy to investigate.

Illi suspects the owls’ deaths were the result of poisons used by farmers in her rural community, because the second bird she found — a great-horned owl — was not damaged at all. The first was badly decomposed.

Days later, her neighbour found two more dead owls. One month earlier, North Saanich Coun. Patricia Pearson found a dead great-horned owl in a ditch in the same area.

“I regularly walk my dog and I’ve seen doped-up voles and mice dying slowly because they’ve been poisoned. My dog has grabbed at them,” said Illi. “It’s a real concern here.”

On July 21, the provincial government imposed an 18-month ban on rodenticides, citing secondary poisoning of owls and other animals up the food chain, including pets.

While the ban on second-generation anticoagulant poisons, or SGARs, prohibits homeowners from using it, many others are exempt — including essential services such as farmers, food-processing facilities, hospitals, restaurants and grocery stores. The Ministry of Environment said it is restricting the sale and use of rodenticides, conducting a scientific review and looking at practices in other jurisdictions to develop a policy.

The ministry said agricultural operators can still use SGARs with proof of agricultural status and while following “integrated pest management principles, including prevention and full consideration of alternatives, with use of pesticides as a last resort when other measures are not effective.”

A spokesman for the ministry said inspectors with its pest management division investigated several North Saanich farms in mid-September following the owl deaths, and no use of rodenticides was discovered.

Illi said provincial pest inspectors told her that they checked two farms and an excavating company on Wilson Road, saying no SGARs were found.

Inspections of vendors and pest-control companies in Greater Victoria have also been completed. Those reports are expected to be posted in the coming weeks on the Natural Resources Compliance and Enforcement website at nrced.gov.bc.ca.

Retailers are restricted because buyers of SGARs must now show proof at point of sale that they qualify for one of the exemptions — either businesses that are considered essential services, licensed pest-control companies or agricultural operators.

Several municipalities have banned rodenticide use on their properties and parks, including Victoria, Saanich and North Saanich.

Illi thought one of the owls she found was alive because its eyes were open. She stored it for a while, but it ended up in the landfill because she didn’t know where to send it.

Victoria’s Deanna Pfeifer, head of Owl Watch B.C., said anyone who finds a dead owl should take a picture to identify the bird, double-bag it in plastic, label with date and location, put it in a freezer, then call the B.C. Interagency Wild Bird Mortality Investigation Protocol at 1-866-431-BIRD (2473).

The agency says reports will be recorded and assessed to determine further investigation on a “case-by case basis.”

Pfeifer said she has collected more than two dozen dead owls since last year. Autumn usually sees an increase in rat activity, followed by reports of dead owls, she said. “The major users [of rodenticides] are still being allowed to use them and that’s frustrating.”

A report from Springer Science in 2009 indicated necropsies on 164 barn, great-horned and barred owls in B.C. revealed that 70% of the dead birds had residues of at least one rodenticide in their livers and 41% had traces of multiple poisons.

Commonly used rodenticides, such as brodifa-coum, bromadiolone and difethialone, are classified as SGARs. They were introduced in the 1970s in response to rodent resistance to first-generation poisons such as warfarin, chlorophacinone and diphacinone.

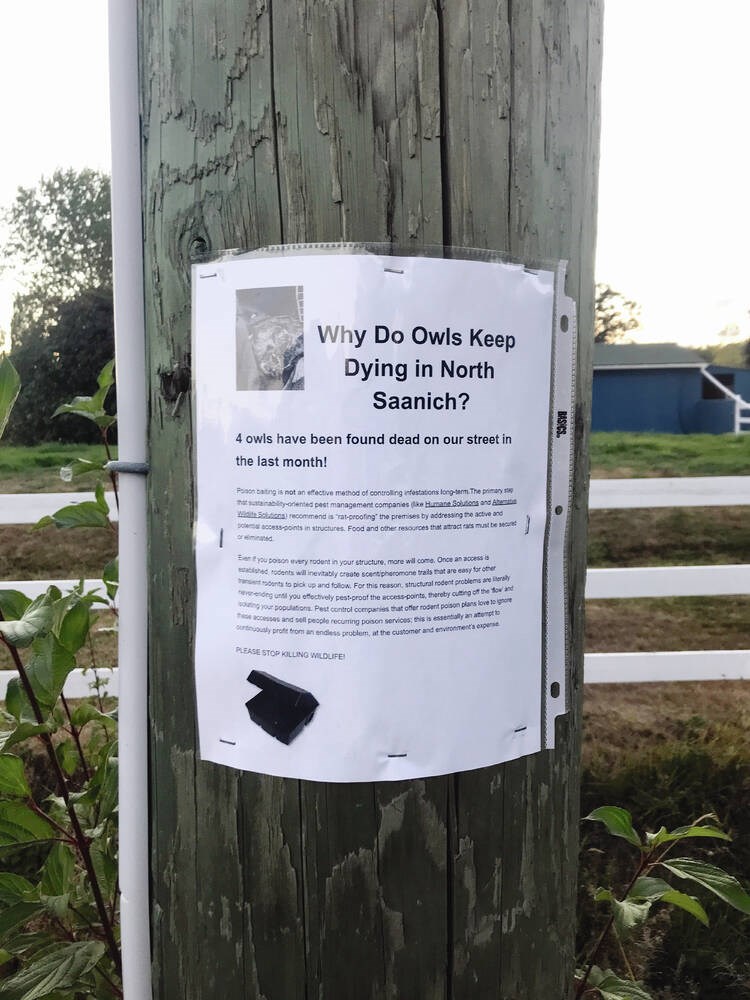

The poisons are often put in black bait boxes, where a rat eats it and dies elsewhere, accessible to pets and birds.

Illi has stapled posters to power poles in the neighbourhood, saying poison baiting is not an effective method in controlling rat infestations in the long term.

She said “rat-proofing” access points and eliminating or securing food sources are the only ways to eliminate the problem, a position shared by the B.C. SPCA. “Pest-control companies love to … sell people recurring poison services,” Illi said. “This is an attempt to continuously profit from an endless problem at the customer and environment’s expense.”

North Saanich council has sent a newsletter with its utility bills, asking residents to look out for dead raptors and to follow the ministry order on rodenticides.

Pfeifer picked up the dead owl found by Pearson and it was sent to the Ministry of Agriculture’s Food and Fisheries Animal Health Lab for examination.

Pfeifer said kidney and liver samples are forwarded to Guelph University, with results turned over to Environment Canada. She has been pushing for results and has had to file a freedom of information request to get data on how many dead owls show traces of poisons.

“I’m so upset at always banging my head against the wall,” said Pfeifer. “Isn’t it up to our government to protect wildlife and human life?”

To report a dead raptor, call the Interagency Wild Bird Mortality Investigation Program hotline: 1-866-431-2473.

To report a raptor that is alive but appears sick, call the B.C. SPCA provincial call centre: 1-855-622-7722.