The statue of Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, was hoisted on a five-point harness from its place outside Victoria’s city hall early Saturday amid cheering, booing and disagreements about the politician’s legacy.

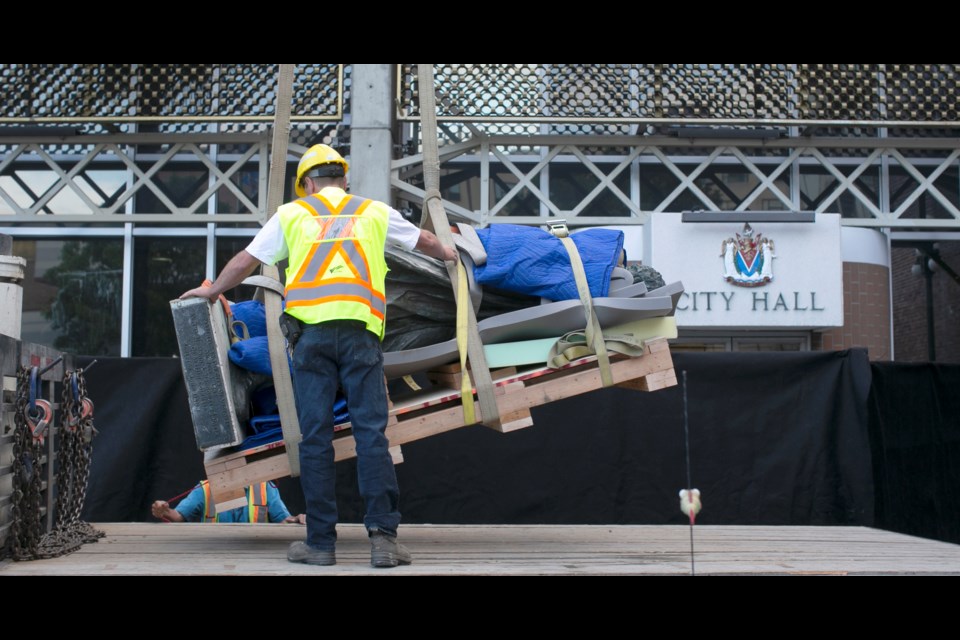

City crews started the process at 5 a.m. after some preparation, including erecting temporary fencing Friday night. The statue was driven away on a flatbed truck by 7:30 a.m. Afterward, crews remained to install an interpretive sign in the statue’s place.

The 635-kilogram bronze statue, installed in 1982, was cut with a saw under its limestone base — the metal rods holding it down were severed — and was removed with much care and attention.

At this point, some bystanders began singing O Canada, while others applauded and some booed.

The final stage of the lift and transportation of the statue was accompanied by people singing “na na na na, na na na na, hey, hey, goodbye” to drown out those with hands on hearts singing O Canada.

Matthew Breeden, one of a few young men wrapped in Canadian flags, said he came down to city hall to show respect for Macdonald, describing the removal of his statue as “like a funeral process.”

“I don’t support them taking down the statue; we want more debate,” Breeden said.

Bradley Clements, 28, held a sign reading: “No honour in genocide.”

Countering opinions that the presence of the statue promotes educational dialogue about history, Clements said: “If that’s the case, it’s failed.”

Clements said few who pass the statue know Macdonald, who was member of Parliament for Victoria from 1878 to 1882, as the architect of residential schools and other policies of assimilation under the Indian Act, and his refusal to supply food to starving First Nations on the Prairies.

“I think the act of removing it is starting that necessary dialogue,” he said.

His friend Kate Loomer, 25, said she has passed the statue — a statue that offends many Indigenous people — and never even noticed it.

“At no point did anyone ever say: ‘Let’s meet at the statue and talk about Indigenous rights and truth and reconciliation,’ ” Loomer said. “That’s the point.”

Tsastilqualus, 64, born and raised in Alert Bay and a fourth-generation residential-school survivor, was proud to witness the removal “of a shameful part of Canada’s history.”

Tsastilqualus wants the statue moved to a museum with an explanation of all facets of Macdonald’s policies — as well as an update on why the statue was moved from Victoria City Hall.

Eric McWilliam, 27, arrived on his electric bike about 5 a.m.

Until two days ago, McWilliam said, he was a fan of Victoria Mayor Lisa Helps, but now he is offended that the mayor shut down public debate over the statue’s removal and that she “and a small group of political elites” made the decision.

“You can’t stop free speech,” McWilliam said.

Barbara Todd-Hager, 58, a television producer who is Métis, said she felt a lot of pride for her Indigenous relations and friends that Macdonald’s discriminatory policies are now being acknowledged.

“This is a really strong statement that bigotry and racism doesn’t have a place in our courtyards or city halls,” she said.

The decision to remove the statue was made by three city councillors and First Nations representatives who met over the past year as part of a reconciliation process. In making their recommendation to city council, they cited Macdonald’s involvement in creating the residential-school system, which forced First Nations children away from their homes and subjected them to abuse.

Several hours after the removal, a protest against the action and the process that led to it grew tense. About 12 Victoria police officers oversaw several angry and loud debates, as people chanting “Hey hey, ho ho, Lisa Helps has got to go” were drowned out by another faction singing “Hey hey, ho ho, white supremacists have got to go.”

Placards read “We’re not erasing history, we are making it,” while others were along the lines of “Sir John A., you’re OK.”

The protest was organized by a group called B.C. Proud.

“Is this really what political correctness has come to?” Aaron Gunn, spokesman for B.C. Proud, asked in a statement. “Toppling a monument to the Father of Confederation, who united us, built our country and delivered on the audacious promise of a national railway. Was he perfect? No. That doesn’t mean we have to tear down what came before us; it doesn’t mean we have to erase our past.”

Retired lawyer Robert Drew was disappointed by the gathering, saying there was no room for civil debate, and he thought to move too deep into the crowd would be “dangerous.”

Police were quick to talk to members of the Soldiers of Odin when they arrived.

The president of the Soldiers of Odin Vancouver Island chapter, Conrad, who declined to give his last name, told the Times Colonist he came to defend free speech and to note his disagreement with the statue’s removal.

“Sir John A. Macdonald is one of our founding fathers, and I think it should stay,” he said.

The group’s Facebook page describes its mission as: “Fighting for your right to free speech, oppose illegal immigration, and help our fellow Canadians.”

Some bystanders expressed concern about the arrival of the Soldiers of Odin, and some moved to the other side of Pandora Avenue.

The protest began to wind down when rain drove many away.

Helps said the small gathering at city hall, with people debating their views on Canadian history, represents democracy and that’s a good thing — “one of the lasting legacies created by Sir John A. Macdonald.”

She was not disturbed by some people asking for her resignation, saying it’s not the first time and it won’t be the last.

Councillors voted 8-1 on Thursday night to ratify a 7-1 committee-of-the-whole recommendation to remove the statue. (One councillor was absent for the committee vote.) Only Coun. Geoff Young was opposed, on the principle that the public deserved to be included in the discussion.

Other councillors who voted for the statue’s removal agreed on this point, explaining they learned about the removal plan only when it appeared on a committee-of-the-whole agenda on Tuesday or on the mayor’s blog on Wednesday.

The Toronto Sun reported that Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s government wrote to Helps on Friday offering to take the statue and erect it on government property, but the offer was rejected.

John Dann, who created the bronze statue in 1981, said he is honoured if his sculpture can engender a discussion about the violence inflicted on First Nations people.

“I am not sure that removing the sculpture is the best way to accomplish this,” he wrote in a letter to the mayor.

The sign erected Saturday in the statue’s place reads: “In 2017, the City of Victoria began a journey of truth and reconciliation with the Lekwungen peoples, the Songhees and Esquimalt Nations, on whose territories the city stands.

“The members of the city family — part of the city’s witness reconciliation program — have determined that to show progress on the path of reconciliation the city should remove the statue of Sir John A. Macdonald from the front doors of city hall, while the city, the nations and the wider community grapple with Macdonald’s complex history as both the first prime minister of Canada and a leader of violence against Indigenous Peoples.

“The statue is being stored in a city facility. We will keep the public informed as the witness reconciliation program unfolds, and as we find a way to recontextualize Macdonald in an appropriate way. For more information please visit www.victoria.ca/reconciliation.”

The metal post and frame for the sign had been fabricated for another purpose and the decal with the inscription took only hours to make in the city’s sign shop — a decision made by city staff after the council vote to remove the statue.