Tour ship companies anchored by the pandemic traded their usual tourists for mountains of trash, collecting 127 tonnes of marine waste along the central coast of British Columbia.

The effort involved the captains and crew of the Small Ship Tour Operators Association of B.C., nine sailing ships, members of six First Nations, 18 Zodiac vessels, a helicopter and a massive barge.

Among the items picked from remote shores were massive chunks of Styrofoam, kilometres of plastic rope, fishing floats, bottles, gas cans and bundles of “ghost” fishing nets that kill and injure fish, whales, birds and other marine animals.

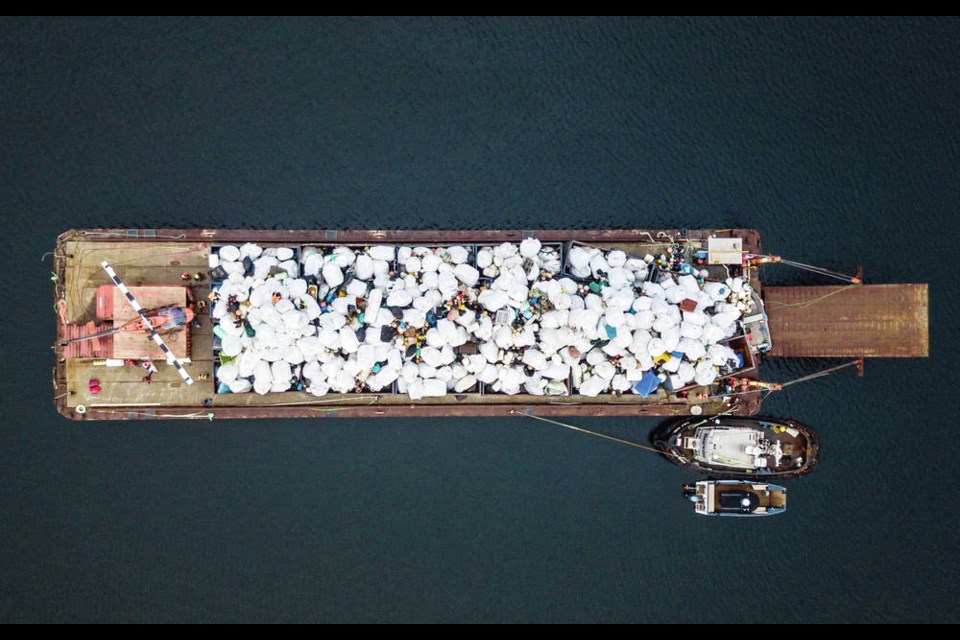

Over 42 days and 1,000 kilometres of coast line, the project collected enough to twice fill a hockey-rink sized barge with bags of debris piled like small mountains. It was offloaded at Port Hardy and trucked to 7-mile Landfill, a former mine near Port McNeill.

The $3.5-million cleanup, financed by the provincial government’s Clean Coast Clean Waters Fund, far exceeded expectations.

Kevin Smith, captain of Victoria-based Maple Leaf Adventures and team lead, said the cleanup saved the tourism companies, whose season was cancelled because of COVID-19, and provided employment for more than 100 crew and Indigenous community members. The final grab of trash also greatly surpassed initial estimates of 20 to 30 tonnes.

“This was an industrial-sized cleanup, something that’s never been done before, and it was an incredible team effort,” Smith said.

“It’s not like walking along Long Beach. This is the wild side of the coast pummeled by storms. It’s rugged, steep, treacherous. We’re moving enormous logs and finding drift netting that’s a half a mile long, and cutting it into sections to get it out.”

The so-called ghost nets can entangle whales, fish and birds, which sink and die. The nets are known to refloat after the animals rot away, again posing a threat.

Smith said about two thirds of the entire load of debris was Styrofoam, most of it from cheaply made Asian fishing floats that leak tiny pellets.

“You walk up from the shore into the salal and see it in the shore, with trees growing through it,” he said. “Future anthropologists digging here might call it the Plasto-scene era.”

At their peak, shore workers were collecting up to 10 tonnes per day, loading the debris into bags of about 320 kilograms each — the capacity of the helicopter — and placing them on beaches or rocky headlands.

Daily morning meetings co-ordinated beach workers, ship and tender crews, helicopter lifts and barge locations. A drone was used to do further reconnaissance along the coast, looking for crucial debris sites.

“We went dawn to dusk, 12-hour days, and there were no injuries,” Smith said. “We all felt we were taking part in something so positive. When a bag was lifted it was pure jubilation.”

Smith said the tour ship operators and crew — many of them scientists — are currently preparing a report for the provincial government. By mid-November a complete breakdown the project is expected to outline in detail where the debris is coming from and why, what the province and Canada can do, and the advocacy needed to stem the debris from other countries.

Smith noted much of the plastics picked up were old, some likely from a larger debris field in the Pacific related to the Japanese tsunami in 2011.

They even found a message in a plastic bottle hurled off the shore of western Vancouver Island in 2003. “It was from someone having a bad day, nothing noteworthy,” Smith said.

Despite the massive haul, the ship operators felt they only managed a small dent in the problem. With their tourism seasons possibly on hold again next season, Smith said operators would welcome the opportunity to do it again.

“We all felt it was a beautiful thing — competing colleagues working toward a common goal,” he said.

Doug Neasloss, stewardship director with the Kitasoo-Xai’Xais Nation, said the initiative provided a rare opportunity.

“Marine debris is an ongoing challenge and a removal initiative of this scale — to clean up a large, remote coastline — is an undertaking that will provide significant environmental benefit to Kitasoo/Xai’Xais territory and beyond,” he said.

The Small Ship Tour Operators Association of B.C. includes seven companies, most of which are based on Vancouver Island.

The key players in the project included Russell Markell of Outer Shores Expeditions in Mill Bay; Ross Campbell of Mothership Adventures on Sonora Island; Comox-based Eric Boyum of Ocean Adventures Co.; and Randy Burke of Bluewater Adventures. Other key personnel included Scott Benton of the Wilderness Tourism Association, and Katherine MacRae of the Bear Viewing Association of B.C.