It would make life easy if anything we needed to know about our own situation could be adequately represented by a letter grade or even a number as we stumble daily though life.

We could simply assign something between A and F as indicators of progress toward personal goals, the quality of a personal relationship or even our own personal physical and mental health.

But representing progress with a letter or a number is not, in the great scheme of things, even remotely helpful as we strive to move toward our goals: personal happiness, career satisfaction, financial security or even willingness to learn.

In 1957, William Bruce Cameron, a professor of sociology, published an article in the Bulletin of American Association of University Professors titled “The Elements of Statistical Confusion Or: What Does the Mean Mean?”

Cameron identified the difficulty of performing appropriate statistical measurements to real life, and coined a phrase that has come to define the difficulty of measuring success in life or learning or any other complicated process: “Not everything that counts can be counted and, conversely, not everything which can be counted, counts.”

Certainly, it is the desire to measure progress in any number of human activities, which is second nature to people. What is not second nature is how to measure progress beyond superficial representations.

That, all by itself, can lead to some significant misinterpretations.

That’s how it can be measuring progress in learning. We sometimes fail to take into account the difference between outcome goals and process goals.

Outcome goals, like mastering the content of a course in Grade 10 math, might fail to recognize the importance of process goals, observable activities that help a student of grade 10 math gain mastery of the content and get closer to an outcome goal — readiness to move to the next level.

Again, in that Grade 10 math class, students might work on mastering trigonometry, finance, algebra, relations and functions, linear equations and systems.

Then, after experiencing success and demonstrating competency in some or all of those areas a designated number of times, students move on to another skill.

Struggling students don’t get Ds or Fs. Instead, they continue to practise concepts until they’ve grasped them — and only then move forward. Teachers, meanwhile, give students updates on their progress, including what they still need to master.

This system allows students to progress at their own pace. Fast learners can advance quickly and excel, while slower learners have the time they need. Success is the desired outcome.

It’s true that what gets measured gets managed, but with learning (and living), managing and measuring progress is a far more complicated process than simply assigning a letter grade or percentage.

What it involves, as well as the “mastery” approach to progress, is frequent live feedback from teacher to student.

Live feedback involves giving students constructive criticism and advice while they work. This is not a matter of receiving an mystery assessment at the end of an assignment, but rather is about students, while they are working toward mastery, receiving guidance, encouragement and input from their teachers.

Self-assessment is another way for students to “own” the progress they are making toward an outcome goal. Self-assessment is a learned skill that enables the learner to identify their specific strengths and weaknesses, and provides individual insight into what may be needed to improve.

Self-assessment is reflective. By establishing their own measures for performance, students monitor their learning processes. It is of pivotal importance in the teaching/learning process that students, not their teachers, gain ownership of their learning.

Self assessment, in turn, should provide the student with some acceptable options as to how progress can be represented.

Portfolios are a way that showcases individual student learning by allowing teachers and students to curate students’ best work and progress as the course proceeds.

A portfolio might include work from throughout the course of the school year. Choosing representative pieces over time encourages students to reflect on the learning process and note how they’ve moved forward — and why.

Letter grades, vague and uninformative as they are about both performance and progress, can discourage students and, as one teacher I know put it: “Once kids give up, it’s all over.”

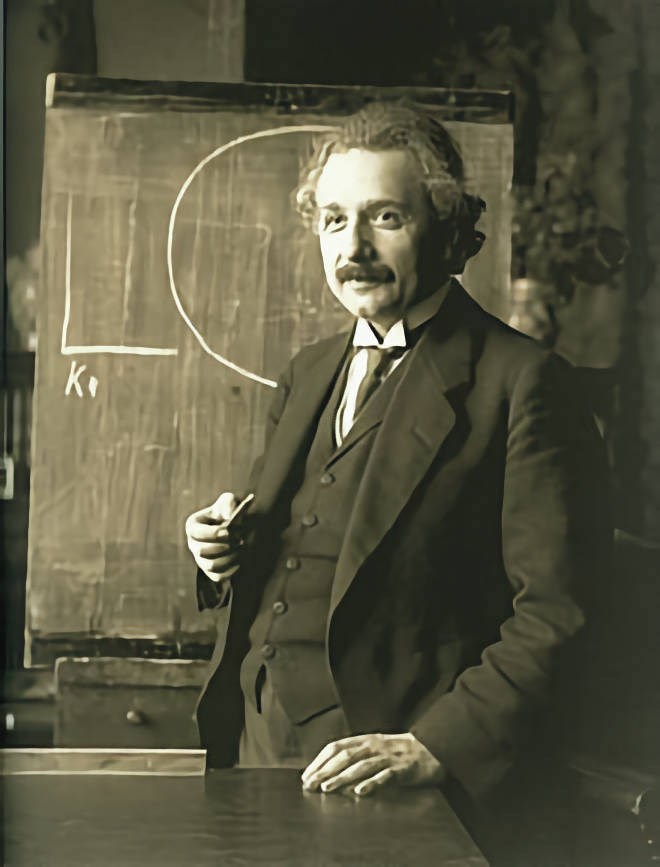

Einstein, on the other hand, ever the optimist about learning, said: “Failure is success in progress.” As the best teachers know, it is important to keep that hope for success alive and well.

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.