Now that teachers in Denver, Colorado, have returned to work and resumed negotiations, it is probably a good time to take a look at the frequently promoted idea of merit pay for teachers.

The Denver merit-pay system called “ProComp” was instituted in 1999 and veered away from traditional experience-and-qualifications compensation scales. It promised salary bonuses for teachers who, having completed training, applied their new skills in the classroom.

“ProComp” also provides incentives for things such as working in hard-to-fill positions in a high-poverty school or even sometimes student results.

But here’s the problem that is now causing Denver teachers to walk out: Merit pay in a school system can’t work like a private-sector bonus system.

In the business world, bonuses and incentives are based on a clear idea of success, whether the definition of success at “Hubcaps 4U” this year is “We made a bunch more money” or “We increased the value of H4U stock this year.”

Public schools, on the other hand, are not profit-driven, and school-district success is hard to define. More high school graduates? Success for kids who make the transition from elementary to secondary school styles of instruction? The school musical filled the auditorium?

This all might sound logical, except that merit pay is an idea that is mostly appealing to people who would never dream of having their own compensation and benefits subjected to such a multi-faceted, 360-degree performance assessment.

Politicians at all levels probably head that list.

Even for CEOs, the merit pay/bonus system tied to company performance too often rides on the backs of those much further down the food chain, who daily check the quality of those hubcaps as they come off the assembly line.

Then there is the incongruous notion, broached by the Denver system, that dollar incentives will encourage teachers to sign up for schools with low pupil performance on standardized tests.

I’m glad my doctor does not subscribe to the idea that it is better to avoid clinics where people are actually sick or, alternatively, be paid more for dealing with actual illness.

As the Harvard Business Review also points out, people work for many non-monetary reasons, including recognition of value by their colleagues and a sense of communal achievement.

But let’s set all that aside for a moment. For merit pay based on “teacher performance” to be in any way justifiable, teacher quality would have to be assessed using the same criteria under the same classroom conditions at the same time of the year and pretty much with the same classroom full of kids.

Even then, the degree of subjectivity that would enter into a decision as to whether to award a merit bonus or not would inevitably lead (and believe me, I’ve been through a few of these) to a grievance procedure that focuses not on the competence of the teacher, but on the competence, experience and assessment record of the assessor.

At its most potentially destructive, the worst possible outcome of a pay-for-performance culture in a school or even school district is that it creates the potential to pit employees against each other and lead to a mercenary and competitive environment.

But back to Denver: It is an irony that it took a sophisticated campaign run by “political consultants” and funded by philanthropies to turn meagre union support — early polling showed only 19 per cent of teachers were in favour — into a victory. In the end, 59 per cent of union members voted in favour of ProComp.

Typically, despite a shaky mandate in the first place, the cost/benefit experts in the system almost immediately began to meddle with the details and increase the size of one-time bonuses, while diminishing permanent raises for teachers who had been with the district 14 years or more — a move that favoured newer teachers over more veteran ones.

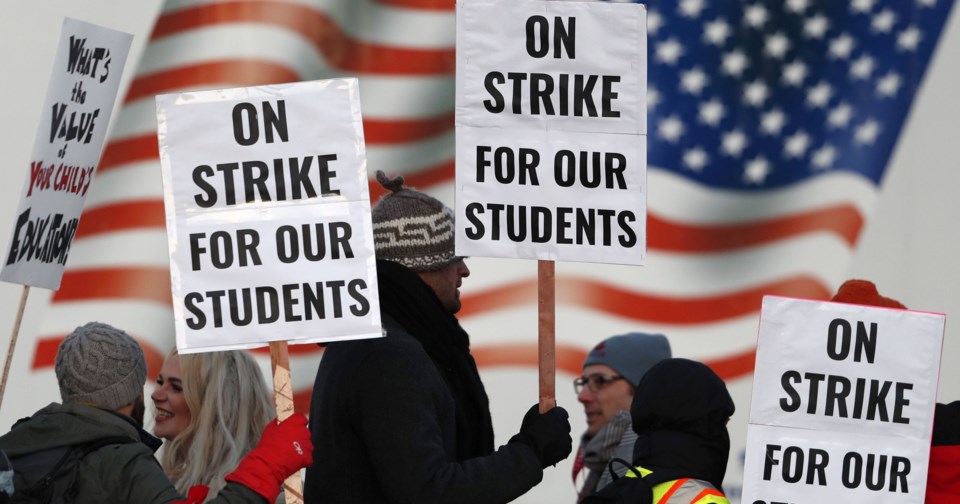

The net result of all this? As reported in the Denver Post, “Faced with a smoke-and-mirrors proposal that continues to lack transparency and pushes for failed incentives for some over meaningful base salary for all,” a teacher strike became inevitable.

So what is the moral of the story? Given that it is irrefutable that better teaching produces better student results, teacher compensation, like compensation in the public sector, should be geared to attracting and keeping only the best and brightest.

Beyond that, a serious commitment to a “teacher internship and coaching” program would produce much better results than “merit bonuses.”

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.