News of facial recognition technology recently resurfaced on several fronts.

A joint investigation of Canadian privacy commissioners revealed in October that one of North America’s largest commercial real estate companies broke privacy laws.

Toronto-based Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited was found to have embedded cameras in digital information kiosks at Pacific Centre in Vancouver, Richmond Centre, and 10 other shopping malls across Canada. The inconspicuous cameras collected five million images of shoppers and employed facial recognition technology to pull together and use personal information without the shoppers’ knowledge or consent.

The company said that their use of the technology was to analyze the age and gender of shoppers, not to identify individuals, and that it had placed stickers at mall entrances about its privacy policy to make customers aware of its practice.

The privacy commissioners deemed this measure insufficient and inadequate, and that the company should have obtained “express opt-in consent.”

Cadillac Fairview also said it was not collecting personal information, and that images were analyzed briefly, then deleted.

But the commissioners found the company used video analytics to collect and analyze the biometric information of its customers. Facial recognition software generated additional personal information about individuals, including estimated age and gender. Furthermore, while the images were deleted, information from them was stored in a centralized database by a third party.

The company has since removed the cameras and says it has no plans to reinstall them. It has also deleted all information associated with the technology that is not required for legal purposes and confirmed it will not retain or use such data for any other purpose.

It’s the latest episode in the ongoing debate about use of facial recognition in Canada.

In February, the RCMP and a number of other police services faced scrutiny when, contrary to earlier denials, they were found to be using Clearview AI, a facial recognition app reportedly being used by more than 600 law enforcement agencies. Clearview AI comes with a database of more than three billion images pulled from the internet, including social media sites like Facebook and Twitter.

The revelations prompted the federal, B.C., Quebec and Alberta privacy commissioners to launch a joint investigation into Clearview AI.

Clearview AI stopped offering its facial recognition services in Canada in July, but many other companies – including Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, Fujitsu, Thales, NEC and Accenture – have or are developing their own software.

Canada Border Services Agency uses facial recognition technology in its NEXUS terminals. It upgraded from fingerprint and retinal scans last year. Vancouver International Airport is the first B.C. airport to switch to the new terminals.

In addition, Canadian passports, B.C. drivers’ licences, and other official government photo ID all include their holders’ unique biometric data.

Those applications barely scratch the surface.

A 2019 study estimated the global facial recognition market would more than double from $3.2 billion US to $7 billion US in revenue by 2024. Another forecast from 2017 suggests annual revenue from all biometrics hardware and software — including fingerprint, voice, iris and facial recognition — will grow to $15.1 billion US worldwide by 2025.

The debate about the technology and Canadians’ privacy and security of personal information will continue as long as gaps remain in Canada’s laws.

But the technology is being put to use for other, more benign purposes, too.

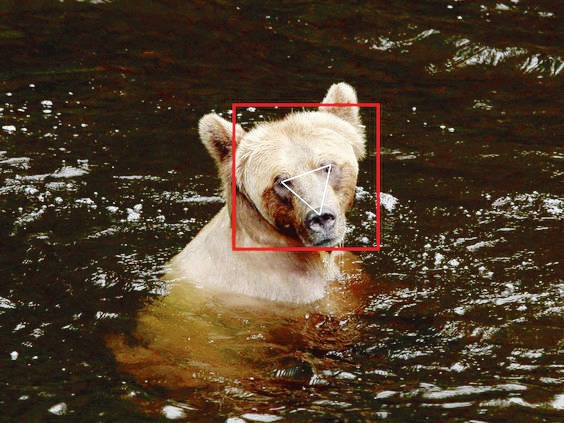

University of Victoria researchers recently teamed up with AI software designers to develop facial recognition–type software for grizzly bears.

The system addresses a fundamental challenge in wildlife research — how to visually identify individual animals in species that lack spots, stripes, or other markings.

But bears not only lack identifiable, individualistic markings, their appearance changes through the year. They pack on the pounds with salmon and grubs in the fall, then emerge lean from hibernation in the spring.

The technology measures a bear’s face repeatedly in multiple dimensions and learns which features are constant in that individual, whatever the angle of the face or regardless of the animal’s age, size, or seasonal portliness.

By facilitating how bears are monitored across the landscape and over time, the tool could transform conservation and wildlife management. Instead of trapping, tagging and taking samples from individual animals, researchers could instead use less intrusive wildlife cameras to track bears’ movements and assess their populations.

Although no one has asked the bears how they feel about their biometrics being used without permission, it’s better than being drugged, tagged and sampled.