On March 29, Island Health reported two cases of measles on Vancouver Island. They are the first Island cases among the 21 reported to date during this year’s outbreak on the B.C. south coast.

Measles hotspots have emerged in Alberta and the Northwest Territories, and a few cases have been reported in Ontario. Seventy-four cases have been identified just over the border in Washington, with health officials declaring a state of emergency in January. Most of the 10 Oregon cases are linked to the Washington outbreak. California has reported 16 cases.

Farther afield, Rockland County in New York state has banned unvaccinated minors from public places to control an outbreak that has infected more than 150 people with measles since October.

Measles is a serious illness. It can cause blindness, pneumonia, inflammation of the brain that can lead to brain damage and ear infections that can lead to deafness. According to the World Health Organization, measles killed more than 110,000 people — mostly children — worldwide in 2017 and is now one of the top 10 threats to global health. Measles is also one of the most contagious viruses around.

Older generations, who grew up with the fear of measles outbreaks in their communities, saw family and friends fall ill with the virus and deal with the lifelong complications. Measles was real, in the face and deadly serious.

So, when the MMR vaccine was made available in Canada in the late 1960s, people didn’t mess around. Kids were vaccinated young, with school nurses providing booster shots in grade school. Adults who had avoided getting measles actively sought out vaccination.

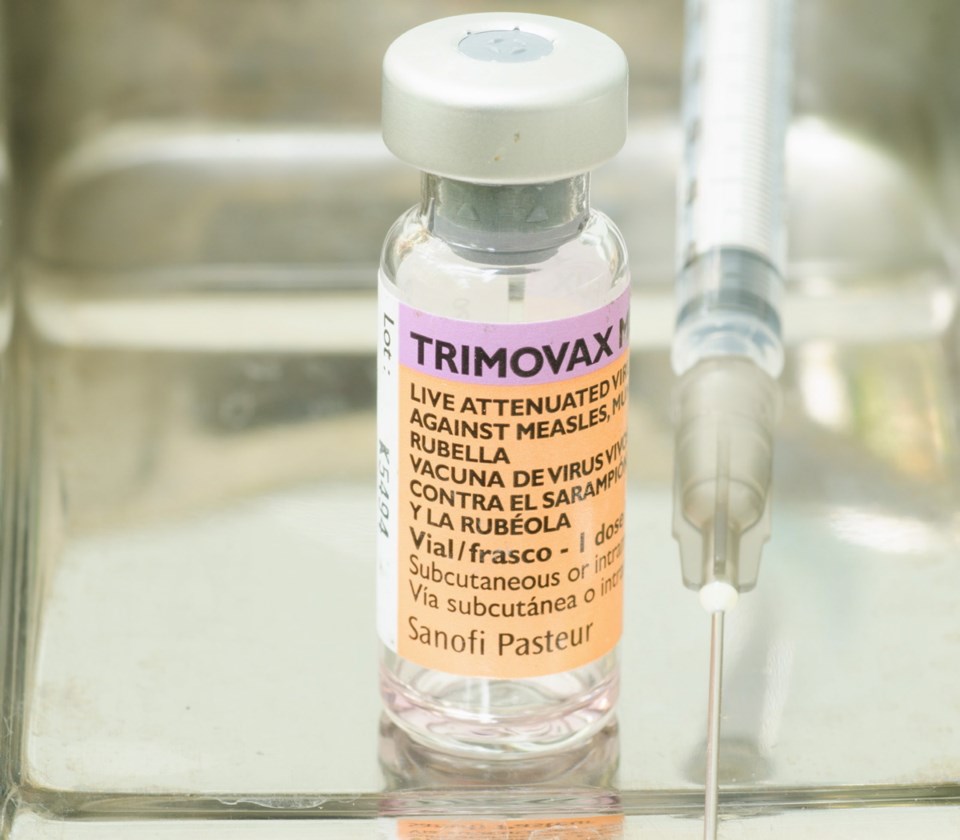

The measles vaccination, which is combined with the mumps and rubella vaccines, is highly effective. Today, the vaccination consists of two doses. The first shot confers 85 to 95 per cent immunization. The booster shot confers 99 per cent effectiveness.

Once measles-immunization efforts started in the 1960s, cases fell quickly and steadily. By 1998, the virus was eradicated in Canada.

Fear of measles also declined. The side-effect of that has been less positive.

Because few of us have watched loved ones suffer from the disease and its consequences, some people now fear measles’ prevention more than the disease. They have fallen prey to doubts, concerns and misinformation that, although repeatedly discounted and debunked, continue to spread.

According to a recent survey by Insights West, eight per cent of British Columbians surveyed still believe vaccines cause autism, 20 per cent said they thought vaccinations exist primarily to enrich pharmaceutical companies and 14 per cent said they doubt the vaccines’ safety.

The irony is that the fear and doubt have flourished only because earlier public-health immunization programs were so successful at removing the threat of the disease. Social resistance to vaccinating against measles is a First World luxury that we have been able to afford only because of previous generations’ determination to vaccinate widely and thoroughly.

Vaccination works on two levels. At the most basic level, it protects the individuals who are vaccinated. Once enough people in a region are vaccinated, however, it also protects individuals who cannot be vaccinated because of allergies, illness, or other medical issues or just being too young to be fully vaccinated.

“Herd immunity” prevents the virus from getting a foothold in a community. But for that widespread protection to occur, 90 to 97 per cent of people in a community need to be vaccinated.

Measles immunization rates in B.C. are lower than they should be to ensure herd immunity.

And, with international travel now common, frequent and fast, the measles virus is now being regularly reintroduced to B.C. by people who return with it from countries where it is still widespread.

The province is looking at a number of measures to respond to the current outbreak and prevent future occurrences. The government is launching a measles immunization catch-up program in April to increase immunization rates. Health authorities will deliver the program in schools for students, as well as in public health units, community health centres and mobile community clinics in select regions.

The government also announced it will start requiring parents to provide proof of immunization when enrolling their children in school, possibly as early as September. This will help keep children safe and help contain school-based exposure.

And it is re-examining a $40,000 provincial grant to a Vancouver charity known for spreading anti-vaccine disinformation.