‘Better things for better living … through chemistry” was a bold and optimistic Dupont advertising slogan that ran from 1935 until 1982.

The phrase — often shortened to: “Better living through chemistry” — has lodged in the public mind as an unintentionally ironic comment on the sometimes dubious benefits of the chemical industry. This industry is the largest manufacturing sector in the world, according to GreenCentre Canada, which claims that: “Chemistry makes everything we do possible.”

While in many respects that might be true, we all know that not all chemistry has brought us better living. The recent Lancet Commission on Pollution and Health reminded us that: “Chemicals and pesticides whose effects on human health and the environment were never examined have repeatedly been responsible for episodes of disease, death and environmental degradation,” and “newer synthetic chemicals that have entered world markets in the past two to three decades and that, like their predecessors, have undergone little pre-market evaluation, threaten to repeat this history.”

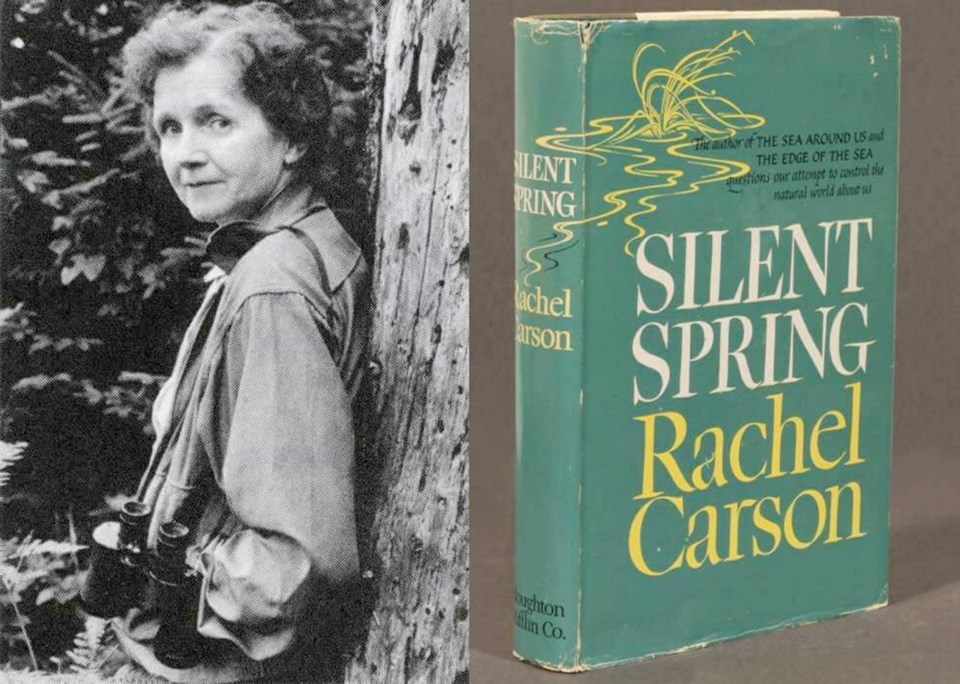

Troublingly, we have known about these problems for decades, but have been glacially slow in addressing them. Rachel Carson warned of the environmental and health impacts of pesticides almost 60 years ago in her 1962 book Silent Spring, but we are still fighting against pesticides such as Roundup and the newer neonicotinoid pesticides, in spite of considerable evidence of their harm. That is hardly surprising when we are fighting against the largest manufacturing sector in the world.

But amidst all that bad news, here is some good news: “Green chemistry” is gaining strength. So what is green chemistry? It is chemistry that is “focused on the design and implementation of chemical technologies, processes, and services that are safe, energy efficient and environmentally sustainable,” according to GreenCentre Canada — a company funded in part by the federal and Ontario governments and with links to Queen’s University in Kingston. It is in the business of “commercializing emerging green chemistry innovations originating from academia and the entrepreneurial community.”

GreenCentre Canada also points to a set of 12 principles, derived from a 1998 book by Paul Anastas and John Warner. These include prevention (“it is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it has been created”); safer chemicals (“designed to effect their desired function while minimizing their toxicity”); use of renewable materials “rather than depleting whenever technically and economically practicable;” and design for degradation “so that at the end of their function they break down into innocuous degradation products and do not persist in the environment.” Hard to argue against that.

In fact, this column was prompted by the recent announcement that a team led by Prof. Heather Buckley of the University of Victoria school of civil engineering — one of a new breed of “green” chemists — had just won first place in a global competition to identify new preservatives for use in cosmetics and household products. According to a UVic statement, the team won for its “reversible” anti-microbial that fights bacteria while in the container but breaks down into two harmless ingredients once outside of it.

The award came from the Green Chemistry and Commerce Council, a U.S.-based organization that “drives the commercial adoption of green chemistry.” Among other activities, the council holds an annual Green and Bio-Based Chemistry Technology Showcase & Networking Event, at which start-up companies get to pitch their new green chemical products. At the most recent event, in May, companies were pitching greener, safer “adhesives, coating technologies, flame retardants, monomers/polymers, ingredients for formulated consumer products (including personal care and household products), and recycling technologies.”

While it might be true that “chemistry makes everything we do possible” and that we want and need the benefits of all — or at least many — of these chemicals, we obviously don’t want all the environmental and health impacts that result. Thus we need to pressure corporations and governments to allow only new chemicals on the market that meet the standards for green chemicals.

In addition, if the new, safer green chemicals are more expensive, governments must use taxation to tilt the market in favour of the greener products, allied with regulations to rid us quickly of the chemicals that bring us worse living.

Dr. Trevor Hancock is a retired professor and senior scholar at the University of Victoria’s School of Public Health and Social Policy.