A commentary by the mayor of Victoria.

This past week has been very challenging as a settler, ally, mayor and Canadian.

Across the country, on the Island, and here in our city, there have been protests in support of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs who assert authority over 22,000 square kilometres in northern B.C., their homelands and traditional territories. Coastal GasLink also asserts authority to build a natural gas pipeline and their authority has been backed by the courts and enforced by the RCMP.

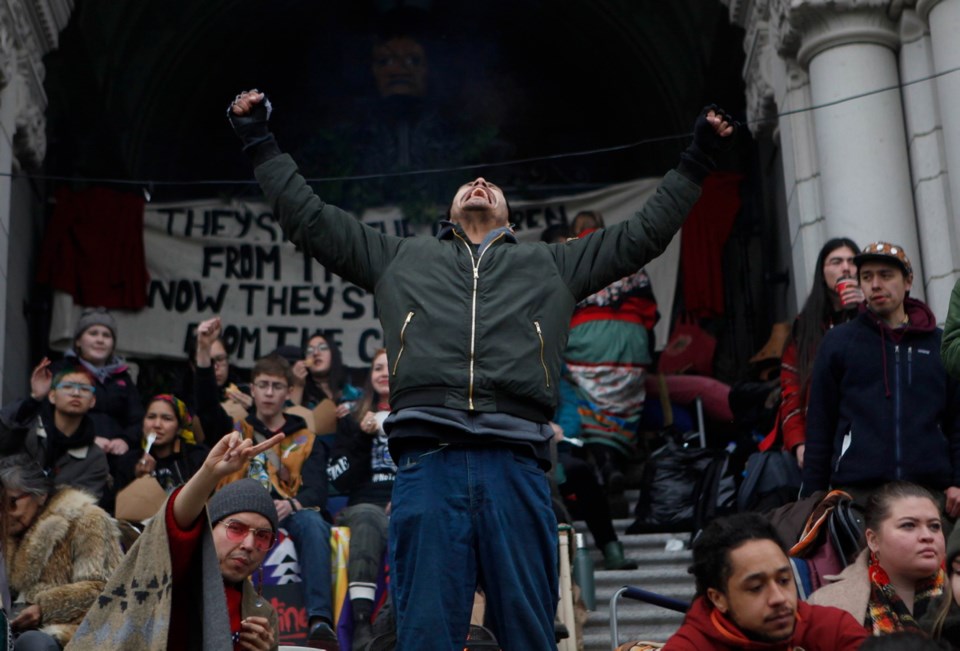

The protests are not surprising. To expect anything other than a vocal show of solidarity with the hereditary chiefs would be to have blinders on to the current historical moment we are in as a country. It’s complicated to say the least.

The federal, provincial and local governments are all talking about reconciliation. At the City of Victoria, we moved a statue of Sir John A. Macdonald from the front steps of City Hall because it caused pain and suffering for Indigenous people. We’ve created the City Family — an Indigenous-informed governance body — to guide the reconciliation process. And we’re hosting a series of difficult but important conversations at the Victoria Reconciliation Dialogues.

The provincial government — by unanimous vote — adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples into legislation. In his thoughtful statement on the protests this week, Premier John Horgan pointed to the complexity of implementing this legislation.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, in his mandate letters, requests that ministers continue “supporting self-determination, improving service delivery and advancing reconciliation.” He directs “every single Minister to determine what they can do in their specific portfolio to accelerate and build on the progress we have made with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples.”

What all of these reconciliation efforts will need to grapple with — and what the Wet’suwet’en situation has brought to light in a clear and practical way — are the multiple legal systems in conflict with one another.

The Wet’suwet’en conflict between elected councils and hereditary chiefs isn’t the first and it won’t be the last.

This a key issue. And this conflict is not new. It was created in 1876 with the adoption of the Indian Act, the reserve system and the imposition of elected band councils.

The residential school system tried to take the “Indian out of the child,” to erase culture, but it ultimately failed. Despite the harm and trauma that the school system caused, which are still felt across the country today, we see the proliferation of language revitalization programs, cultural resurgence, and youth — like those at the legislature this past week — proud to be Indigenous.

As the residential school system took aim at language and culture, the Indian Act aimed to obliterate thousands-year-old legal systems that had a different understanding of rights, responsibilities and relationships. But it didn’t succeed, entirely.

In 2018, the University of Victoria launched the world’s first Indigenous law program. Students of the four-year program graduate with professional degrees in both Canadian Common Law and Indigenous Legal Orders. What we’re seeing alongside a cultural resurgence is the rise again of Indigenous legal orders and an assertion of their rightful place in establishing law and order in the lands we know as Canada.

In this context, the protests are not surprising. They are the result of tectonic plates of different legal systems grinding against each other.

When served with an injunction to clear the rail tracks near Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, Andrew Brant said, “The [injunction] doesn’t mean anything; it’s just a piece of paper. To us, that is not our government; that’s not our law, so when they serve it to us, it’s just a piece of paper.”

If we continued to look only through a Canadian/colonial legal lens it would be easy to dismiss Brant’s point of view. It would be easy to dismiss the protests here in Victoria and across the country. It would be easy to point to the 20 band councils along the Coastal GasLink pipeline route and say that they have approved it and are seeking benefits for their communities.

This is true and important and clearly established within one legal order. And goodness knows economic opportunity for First Nations communities is a good thing. At the same time, to completely dismiss the established authority of hereditary chiefs in Wet’suwet’en territory or elsewhere puts one legal order over another. And pits Indigenous people against each other.

Moving statues, passing UNDRIP and giving strong mandate letters to federal ministers are all important steps. For reconciliation to be successful we must find a way to have Indigenous legal orders side by side with the Canadian one. Until this is resolved — and it will take years, if not decades — we can expect the protests and resistance to continue.