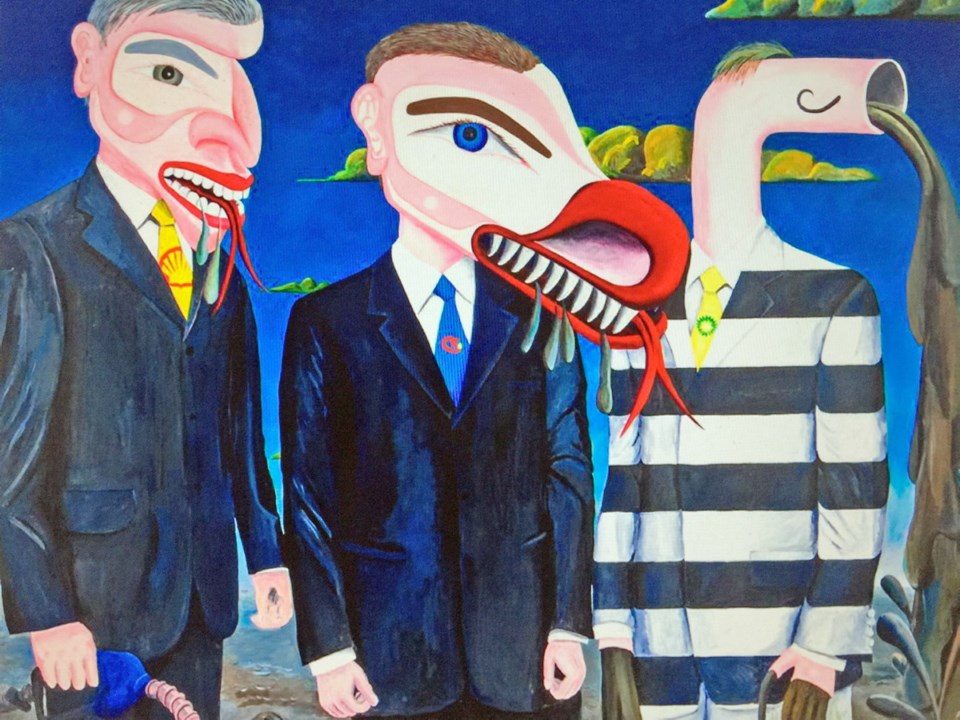

In his amazing 2016 exhibit “Unceded Territories,” Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun called for the renaming of British Columbia (#RenameBC). Almost all of the province is unceded, he said at the time: “This is why I’m asking for the change, because Canada doesn’t own this province, we’ve never surrendered it. It belongs to all native people in this province and their nations have to be recognized, not British Columbia.”

The struggle of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs to assert sovereignty over their land highlights the urgency of not only getting rid of “British Columbia,” but also having settlers in this province recognize that the lands they work and play on remain Indigenous, never ceded, never conquered.

From Tyendinaga Mohawk blocking CN Rail near Belleville, Ont., to activists blocking the Port of Vancouver, to Indigenous youth occupying the B.C. legislature, and Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en blocking CN Rail at Hazelton, a movement on the scale of “Idle No More” is coalescing.

Even the Hospital Employees’ Union, the Longshoreman’s Union and other unions, long the bedrock of NDP support, are stepping up.

Unfortunately, some in the media seem intent on ignoring this important resurgence of Indigenous sovereignty despite the fact the B.C. and Canadian governments are facing a crisis of legitimacy.

First Nations and their supporters are entirely within their rights to rebel, to engage in civil disobedience for there are two sets of laws in this land – Indigenous law and settler law. Today, settler law stands on trial, and Indigenous law fully backs the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs who are exercising their lawful rights on their territory.

The courts today recognize the validity of Indigenous laws. The courts have also tried to assert the validity of settler laws, but here they stand on shaky ground — that’s why Premier John Horgan’s appeals to “law and order” are so off-base.

All courts, including the Supreme Court of Canada, have ruled that the lands now called “British Columbia” only came under settler (British) control in 1846 with the signing of what is known as the Treaty of Oregon. That treaty was signed by the British and American governments — not with First Nations even though they outnumbered non-Indigenous people at the time 1,000 to 1. The treaty was with the United States.

In the discussions leading to the treaty, the only way the British could justify their desire for expansion was to say that Captain Cook and Captain Vancouver had discovered “British Columbia.” Such assertions, known today as the Doctrine of Discovery, have been totally discredited by Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples the world over.

In its 2007 Tsilhqot’in ruling, the B.C. Supreme Court itself ruled early explorers were engaged in actions no better than “Captain Vancouver’s act of imperialism.” If the judges had bothered to read the content of the negotiations justifying the Treaty of Oregon, they might have realized that to suggest the Treaty of Oregon provides any basis to Crown sovereignty is like arguing “Columbus discovered America”!

To make matters worse, it is well-known that B.C. was the “bad boy” of Confederation. After joining Canada in 1871, the legislature of white men, representing a minority of white settlers, passed laws taking away the right to vote of the estimated 40,000-plus First Nations and Chinese then in the province. Though the attorney general of B.C. said that such an action was racist, none other than John A. Macdonald authorized it.

The B.C. government then refused to even discuss treaties with First Nations, even lobbying the federal government to impose a ban on First Nations going to court from 1927 on.

First Nations sovereignty over their territories does exist and much can be learned from their traditions. For W̱SÁNEĆ peoples, terms such as as TEṈEW̱ and NEHIMET, or for Nuu-chah-Nulth peoples terms such ḥahuułi and ḤuupuKʷanum continue to represent spiritual and legal beliefs founded on an organic sense of being in which people do not own the earth but rather belong to it.

Thanks to the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, we now know that they too retain similar concepts in terms such as Anuc’nu’at’en.

As the protests spread, wherever they take place, we hope First Nation band councils will step forward to support the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, protecting the protesters by asserting the Nations’ laws, shielding the protesters in a cone of love and respect. Municipal councils can follow suit, support the protests, and stop the provincial and federal governments from trashing UNDRIP and any possibility for reconciliation.

In the name of Indigenous law, let us make things right — for the land and for the generations to come.

Nicholas XEMŦOLTW̱ Claxton teaches in the University of Victoria’s Faculty of Human and Social Development and is elected chief of the Tsawout First Nation. John Price is UVic professor emeritus (history). They recently published “Whose Land Is it? Rethinking Sovereignty in British Columbia,” in B.C. Studies.