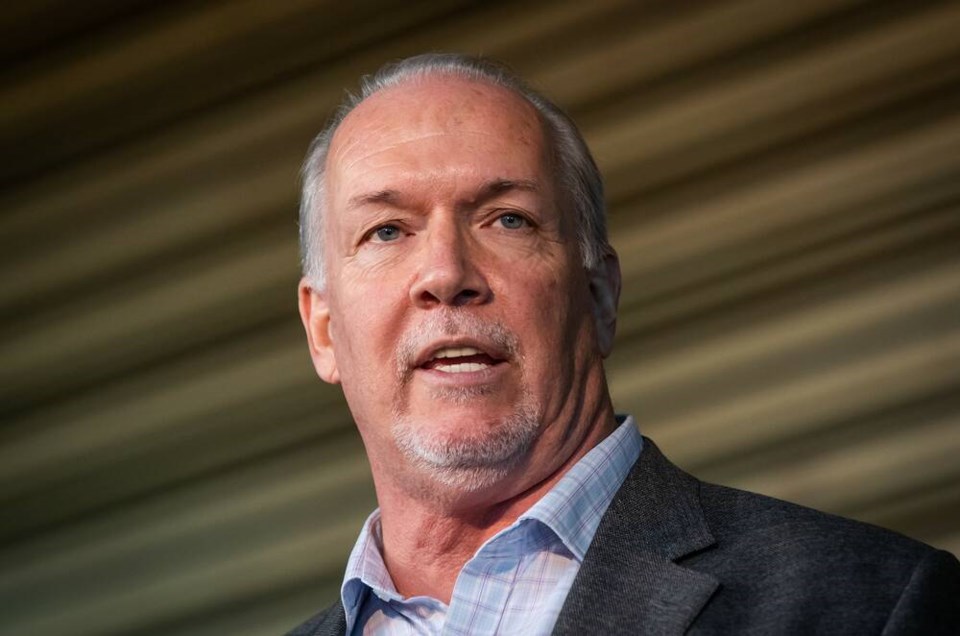

While John Horgan remains the most popular premier in Canada, there are warning signs for his government.

When the NDP took office in 2017, forming a minority administration with the support of Green Party MLAs, they pursued a cautious and politically centrist agenda.

Perhaps the most striking example was the decision, despite opposition from the party’s activist wing, to complete the B.C. Hydro Site C dam. While controversial, it was a concession to the cards already dealt that voters found reassuring.

But since gaining a strong majority in the 2020 election, there are signs the NDP is moving away from the middle ground. That could open the door for a B.C. Liberal Party comeback.

The most recent example was Horgan’s refusal to reduce the tax on gasoline even as prices soared above $2 a litre. Alberta has already taken this step, and there is pressure in other provinces to follow suit.

His desire to maintain his party’s climate change policies is understandable, but at what cost to distant rural communities and those least able to pay?

Then there was the government’s decision to impose its own valuation on how much a car should sell for.

To date, when an automobile changed hands in B.C., both the buyer and seller certified in writing the sale price. It is against the law to file false information for the purpose of tax evasion.

However, starting later this year, the Finance Ministry will ignore the certified price and impose its own valuation, if the reported price is lower than average for that vehicle.

In effect, the government has given itself the authority to assert what a car sold for, regardless of what the buyer and seller say.

There was the recent decision to emasculate the B.C. Ferries board of directors and quash the company’s independence. There is a certain deafness here, considering the fast ferry debacle that occurred when the NDP last ran B.C. Ferries as a Crown corporation and dictated policy.

February’s budget reminded us of the fiscal excess that marked the NDP administrations of the 1990s. Provincial debt is forecast to increase 93 per cent by 2025.

The deficit is estimated at $5 billion, and throughout the government’s remaining term of office, never falls below $3.2 billion. And over the next year, thousands of new full-time equivalent jobs will be created in the public sector.

There is no indication here that a return to financial stability is anywhere in sight.

Certainly it can be argued that after more than a decade of the tight-fisted grip imposed by premiers Gordon Campbell and Christy Clark, some relaxation was due.

There are natural cycles in politics, and a leftward swing is often required to restore the balance after some years of right-leaning policies.

However the key word here is “balance.” The idealism that animates NDP governments is admirable. Yet moderation is also a virtue.

Horgan was able to rein in the tendency to overreach during his first term of office. That was necessitated by his weak hold on power.

But with this constraint now removed, can he find the right combination of progressive policies and fiscal prudence? Can he avoid overplaying a momentarily strong hand?

We are inclined to think that if anyone can, Horgan can. Yet activist parties are always hard to manage.

In a sense, the COVID outbreak simplified the business of governing over the past two years. There really was only one priority, and strong public support for fighting the virus overcame any objections on other fronts.

Now that it appears the worst of the outbreak may be over, there is less room to manoeuvre.

The challenge for Horgan is to hold his caucus together while steering a more moderate course than some of his colleagues may prefer.