Advisory: This editorial includes details of a violent sexual assault.

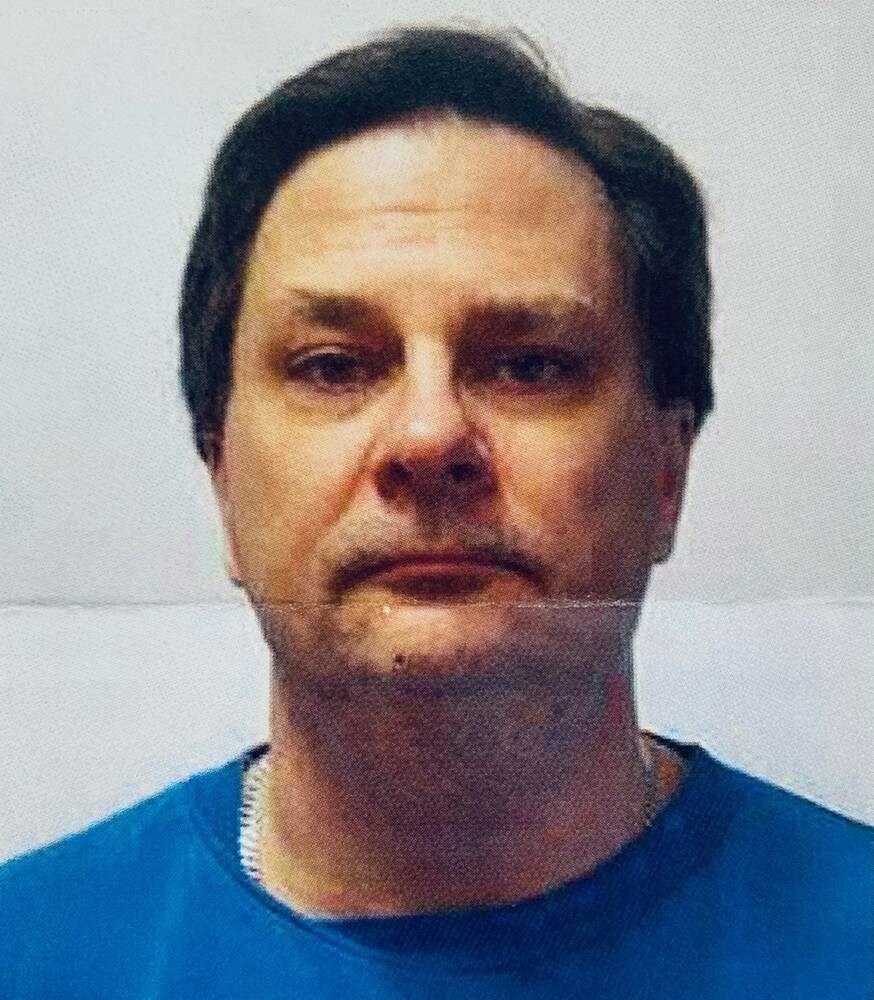

A convicted murderer out on parole, Kenneth MacKay, was arrested this month in Victoria after a report that he was stalking a young woman.

In December 2000, MacKay killed 21-year-old Crystal Paskemin in Saskatoon. The details of the murder are grim.

MacKay offered the young aboriginal woman a ride home, sexually assaulted her in his truck, broke her jaw with his fist, then drove his truck over her head, crushing it.

After setting her naked body on fire, MacKay dragged it behind his truck, then buried the remains in a shallow grave.

In 2002, MacKay was found guilty of first-degree murder, and given the required minimum sentence of 25 years without parole.

How did it happen that a man sentenced to 25 years without parole was given parole?

Some history is required. In 1976, when the death penalty was abolished, a mandatory sentence of 25 years was substituted.

However, to meet calls for rehabilitation, a “faint hope” clause was added, permitting the possibility of parole after 15 years. But there were soon suggestions of abuse.

Noting that over the next three decades some 135 offenders were granted parole, Stephen Harper’s government repealed the faint hope clause. However, the provision allowing parole three years before the end of the sentence remained on the books.

A more troubling question is why MacKay was considered a suitable candidate, and why he was released with such unseemly haste. MacKay was paroled in January 2023, the first moment he became eligible.

When asked, Lisa Saether, regional manager for the Parole Board of Canada, said this, “When making its decision, the board conducts a thorough risk assessment to determine whether the offender’s risk remains manageable in the community. Public safety is the paramount consideration in all PBC decisions.”

But how can that be? A psychologist warned the board that MacKay was a high risk for violent re-offending. The Correctional Service of Canada advised against his release on the same grounds.

His institutional parole officer reported that MacKay was unable to take “no” for an answer, and that he harboured anger toward women when he killed Paskemin.

The Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations spoke out against his parole.

So if public safety is the “paramount consideration,” why was this man released?

The parole board won’t answer that question. It styles itself “an independent administrative tribunal.”

Yet that does not confer unlimited freedom of action. As in any other sector of the public service, accountability is still required.

We cannot have parole officers acting as a law unto themselves. Specifically, when decisions are made that are inconsistent with the board’s own policy, as this decision was, some form of recourse is required.

And indeed the means exist to hold the board accountable.

All of its members are government appointees who report to the federal minister of public safety, Dominic LeBlanc.

It is his job to ensure that parole policies are framed in a manner consistent with public values, and followed in a steady and transparent manner. Clearly that did not happen here.

So what should LeBlanc do? The answer seems clear. It is up to the minister to see that board members understand what is expected of them.

Like any government agency, the board exists by leave of the public. With people increasingly worried about the growing tide of violence in our cities, this is the paramount fact that should guide decisions.

If the English language means anything, 25 years without parole should mean just that.

While there may, on rare occasions, be an exception, Kenneth MacKay was not one of them.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]