In 1968/69, I taught at a “selective/regional” New South Wales public high school for “gifted” kids grades 8 to 12.

Students were selected on the basis of what has been described as “schoolhouse” giftedness, meaning test-taking or lesson-learning giftedness.

As I learned from the kids at this school, there is much more to “giftedness” than that.

The term and its descriptors are widely misunderstood, even by some who are in the teacher-training business.

An example of this occurred when I was teaching a demonstration lesson on Shakespeare’s play Macbeth for teacher trainees and their instructor from the local teachers’ college.

Teaching literature to senior high school students involves teaching novels, poetry and drama at three levels: a literal level (what do the words mean?), an inferential level (how do the words relate to the story or theme of the piece?) and a critical level (where the teacher has students make judgments or decisions about what they are reading that they must explain and defend during a class discussion.)

Studying Macbeth at the more complex critical level was what these kids were ready for.

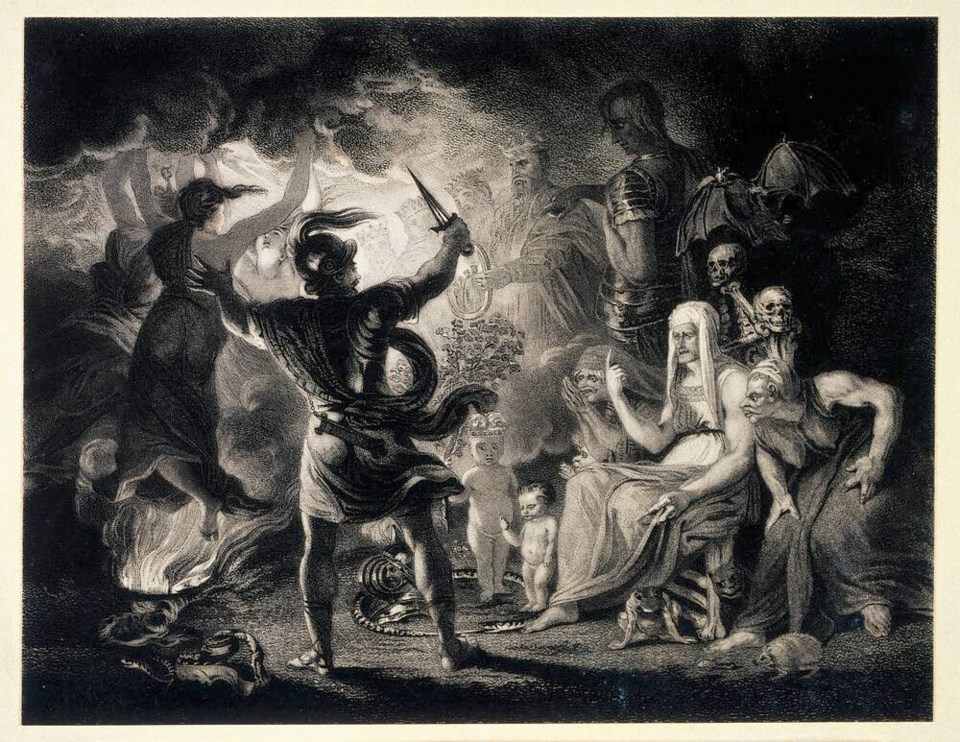

I asked them what the options were for interpretations of the scene in Act 2 Scene 1 of the play where Duncan, the king of Scotland, was visiting Lord Macbeth’s castle and sleeping in his chambers.

In an earlier scene, three witches had made predictions about Lord Macbeth’s future and it had become clear that Macbeth himself had kingly ambitions.

In the scene in question, Macbeth and his colleague Banquo, another Scottish lord, were involved in what might be a very ambiguous conversation about the night ahead.

BANQUO

All’s well. I dreamt last night of the three weird sisters: To you they have show’d some truth.

MACBETH

I think not of them: Yet, when we can entreat an hour to serve, We would spend it in some words upon that business, If you would grant the time.

BANQUO

At your kind’st leisure.

MACBETH

If you shall cleave to my consent, when ‘tis, It shall make honour for you.

BANQUO

So I lose none In seeking to augment it.

One student put up his hand: “If we were making a movie of this scene, we could change the interpretation by how we lit it.”

“Show me what you mean,” I said.

He came up to the blackboard and drew two stick figures.

“Look, if we lit the scene from below and up at the characters, it would create shadows on their faces and the scene would take on a dark mood, but if we lit it from above there’d be no shadows and it could be just an innocent conversation between two friends,” he said.

That triggered a class discussion about the scene and the ambiguity of the dialogue.

After the lesson, the teachers’ college instructor came up and thanked me, but added: “next time we come, we’d like to see a lesson that had not been so carefully rehearsed.”

I realised I would be wasting my breath trying to convince him that these kids approached literature at this level every day.

The student who drew the stick figures had just demonstrated the widely accepted definition of giftedness proposed by Dr. Joseph S. Renzulli, director of the National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented at the University of Connecticut.

Giftedness, says Renzulli, requires three characteristics: above-average intelligence, creativity and perseverance, and two out of three characteristics does not satisfy the definition.

Beyond that, Renzulli suggests there is more than one type of of giftedness, i.e. there is “schoolhouse giftedness” and “creative-productive giftedness.”

Schoolhouse giftedness, he says, “might also be called test-taking or lesson-learning giftedness.”

“Creative-productive giftedness,” on the other hand, describes those aspects of human activity and involvement where a premium is placed on the development of original thoughts, material and products.

In my own family, my cousin Graham missed out on “schoolhouse giftedness,” but the creative -productive world of business did not. Graham built a thriving tow-truck business from a single truck that made him a multi-millionaire.

Being academics themselves for the most part, teachers and administrators sometimes miss the hidden aptitudes kids do not always have the opportunity to demonstrate in a classroom.

As wartime gifted British leader and historian Winston Churchill put it about his own classroom experience: “I should have liked to be asked to say what I knew. They always tried to ask what I did not know. When I would have willingly displayed my knowledge they sought to expose my ignorance. This sort of treatment had only one result: I did not do well on examinations.”

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]