Why is now the time to re-emphasize the importance of teaching science K-12 in our schools? Because science, even in the earliest grades, teaches kids how to separate fact from fiction, self-serving speculation from empirically established truth.

Is kindergarten too early for kids to be introduced to scientific method? No, because science comes naturally even to five-year-olds who are curious about everything they observe and are ready for answers to their questions which balance information with more questions.

That alone might make science the most important curriculum in the school program.

These days, an overflowing petri dish of graceless skepticism about scientific truth is dished up beside that bottomless bowl of superfluous and untested information that mesmerizes some followers of social media.

Many people, including politicians, who should and in fact actually do know better, have no problem publicly attracting headlines and news clips by expressing doubts about the validity of scientific findings about everything from COVID-19 to climate change.

Much of that faux cynicism is often based on wildly unsubstantiated conspiracy theories supported by people looking to politically validate, on behalf of “those below” commonly held distrust about “those above.”

That includes scientists and science itself, which to many people is a closed book.

As a vote-getting strategy anti-science platforms seem to work. “Realpolitik” is politics based on pragmatic rather than moral or ideological considerations. People vote for stuff they want to believe, to heck with these scientists and their fancy laboratories.

A net result is an increasing distrust of science and scientists who have the irritating habit of telling truth to power when power has other agendas and obligations.

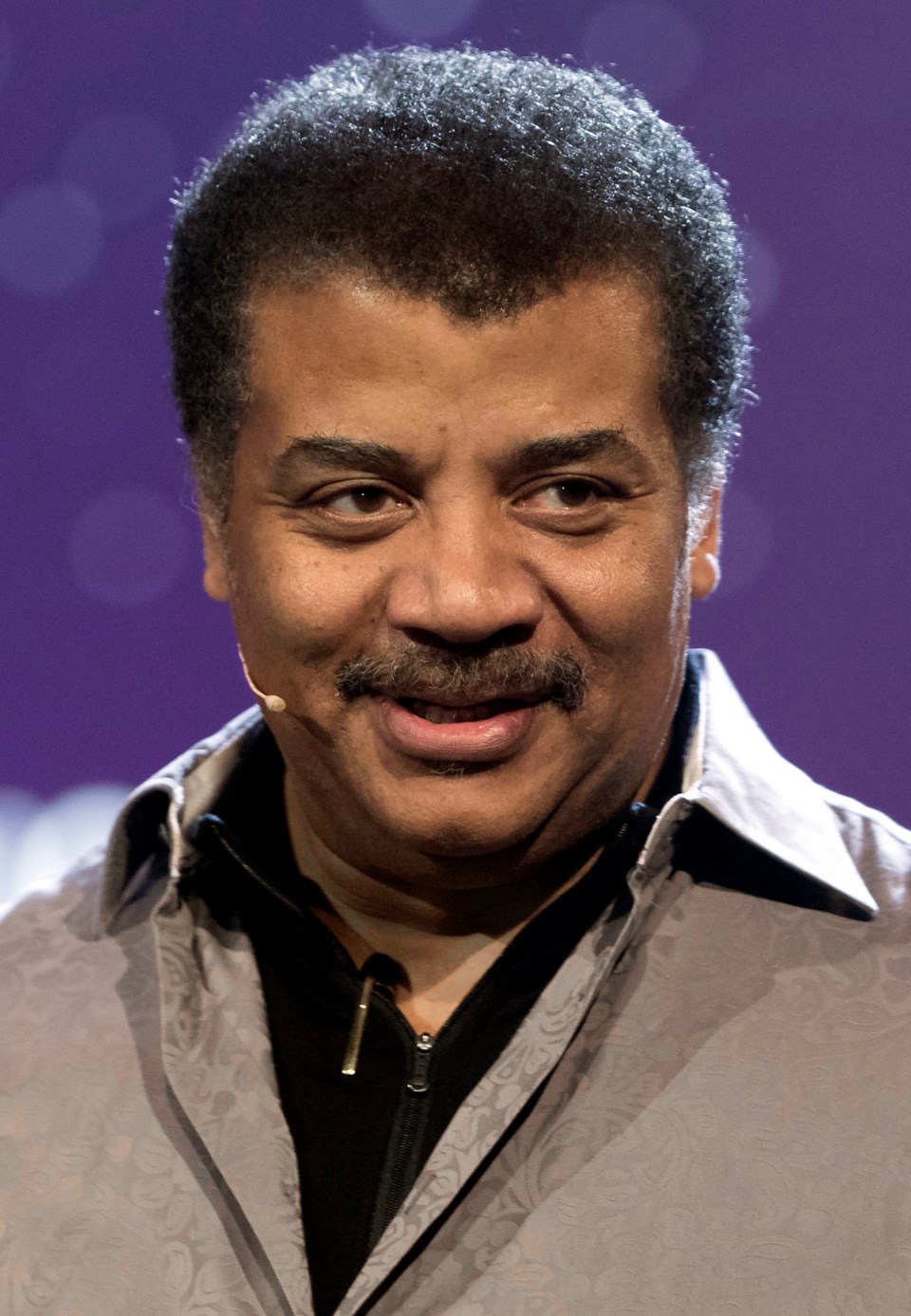

That’s all too bad, because as high-profile astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson wrote: “Science needs the light of free expression to flourish. It depends on the fearless questioning of authority, and the open exchange of ideas.”

And that, as we frequently see on the nightly news, just does not sit well with some people.

Actual knowledge, if it does not align with what people want to believe, explains common conspiracy theories: The moon landing hoax, chemtrails, the Holocaust hoax, 9-11 was an inside job and even COVID-19, which is a hoax and a politically motivated plot.

Kids from age five onwards are bombarded with this stuff — sometimes even at the kitchen table.

Seeking and accepting scientifically determined truth has become an uphill battle with “political ideology” heading the list of reasons for distrust of science.

Sadly, pollsters and commentators who write about this distrust suggest that science skepticism cannot simply be remedied by increasing some people’s knowledge about science.

Why? We’ll leave that to the sociologists, but in the meantime we educators need to rethink the about what we know, have always known, about the value of science in our schools, K-12.

We know that teaching science K-12 helps children develop genuine life skills including an ability to think logically, form opinions based on observation and be willing to subject a “best guess” and a “gut feeling” to a rigorous methodology of measurement, testing, data collection and a willingness to accept or reject opinion on that basis.

Science, beyond test tubes and Bunsen burners, fosters a system of thought and experiment called the scientific method. It’s where students start with an idea, create a concrete way to prove or disprove that idea, keep track of their findings and objectively represent a conclusion about the results of their investigation.

Understanding the importance of evidence that tests theory helps kids learn to think critically.

That process promotes a healthy skepticism, not about science itself, but about beliefs and claims not proven empirically beyond someone’s intuition or just “feeling it in my bones.”

The B.C. Science curriculum explains it like this: “With a focus on inquiry and conceptual learning, the Science curriculum provides students with opportunities to ask questions, consider a range of views, recognize their beliefs and opinions, work collaboratively, and ultimately make informed conclusions.”

In a paper commissioned by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, Mark Windschitl of the University of Washington points to problem solving as a key desired learning outcome of a science lesson at any level: “in problem-solving, students use their understandings of concepts, systems, instruments, materials, and procedures to solve self-defined or teacher-defined problems.”

The best secondary school science labs do exactly that by requiring students to choose their own equipment and construct their own experiments to satisfy a solution to an observable chemical or physical conundrum.

“Science,” wrote 20th century mathematician and biologist Jacob Bronowski, “is the acceptance of what works and the rejection of what does not. That takes more courage than we might think.”

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.