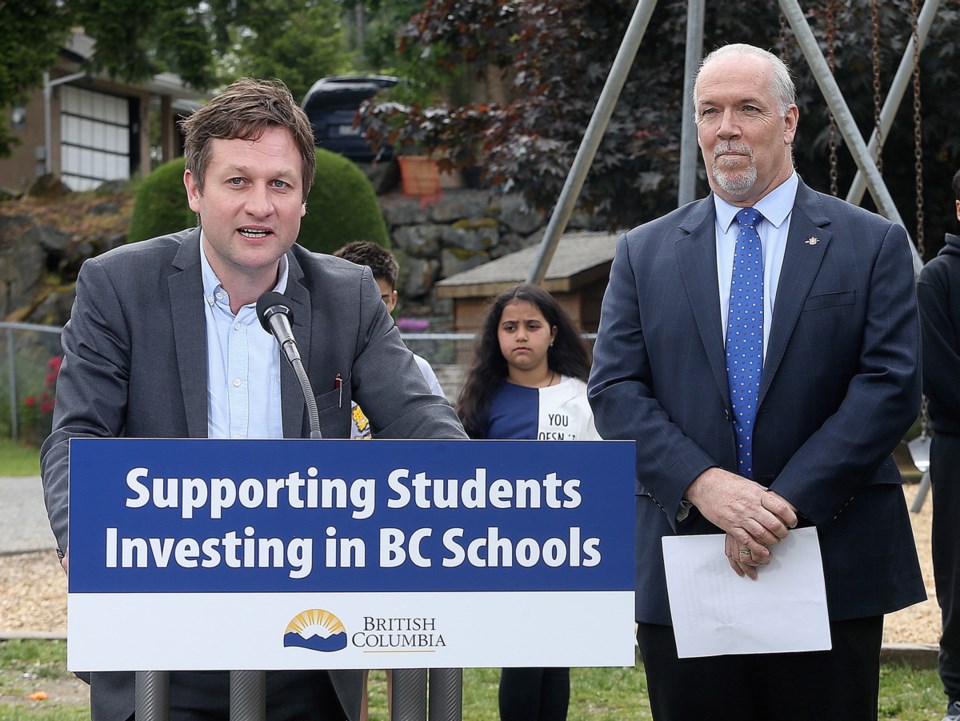

When students return to class in September, NDP education minister and Victoria-Swan Lake MLA Rob Fleming will also be going back to school.

He faces two big tests this year — the funding model and teachers’ collective bargaining. How he fares has huge implications for the schools and the minister’s political fortunes.

The NDP has increased ministry operating grants to districts (“block” funds) only modestly since taking power — by approximately $200 million per year, in a $5-billion provincial education budget. The Education Enhancement Fund, which stems from the Supreme Court ruling against the B.C. Liberals for “stripping” classroom size and composition language from the teachers’ collective agreements in 2002, has injected about $350 to $400 million per year on top of that.

However, as Fleming will no doubt soon learn, school trustees are not shy about asking for more money from Victoria. The Liberals boosted K-12 spending during their three terms in government, from about $4 billion when they took power, to more than $5 billion at the end of their mandate. (And it bears mentioning that enrolment declined in most of these years.)

Yet the party was still easily tarred, by Vancouver trustees in particular, with accusations it was “underfunding” schools. Those same Vancouver trustees refused to balance their district’s budget in 2016, forcing the ugly showdown that ended with the government dismissing them.

Fleming and the NDP will try to skirt school-trustee demands for more money by shaking up the school funding model. The government launched the B.C. Education Funding review in 2017, with a promise to deliver “stable and predictable funding.” A new model is due this fall.

If the expert review team presents one that gives more money to all districts and to programs for all types of students (e.g. regular and special education), trustees probably won’t complain. Fleming will be able to say that he has finally cleaned up the funding mess his party blames on the Liberals. If, however, the new model — even accidentally — reduces funding for some districts and not others, or if it reduces funding for some programs and not others, then Fleming can expect poor marks from trustees and the public.

Fleming’s other test this year is contract negotiations with teachers. Negotiations between the B.C. Teachers’ Federation and the B.C. Public School Employers’ Association are expected to begin in late 2018 or early 2019 for a new multi-year collective agreement. The employers’ association bargains with the teachers’ union on behalf of the government and the province’s 60 school districts.

Fleming recently removed Michael Marchbank, the public administrator the Liberals placed in charge of the employers’ association in 2013. Marchbank’s one-man operation was supposed to control union demands by taking a harder line than the employers’ association’s multi-member board might be expected to.

That board — which Fleming restored a few months ago — is composed of seven school trustees from around the province, plus four provincial public servants appointed by the government. Fleming might discover that the restored employers’ association has a more sympathetic ear to the teachers’ demands.

The Supreme Court decision on classroom size and composition gave the teachers’ federation a big win on bargaining working conditions. Now it will be able to turn its full attention to bargaining for better pay. B.C. has the second lowest teacher pay in the country.

The most favourable outcome for Fleming and the NDP would be a reasonably sizable raise that would help recruit against the current teacher shortage. (The teachers’ federation has filed a grievance about the shortage that cites low pay, among other issues.) If a pay raise eases the shortage, Fleming will be able to boast about solving that problem, as well.

However, if the teachers’ federation decides it has an opportunity with the labour-friendly NDP to make wage gains and further gains on working conditions — for instance lowering class size again — then costs could quickly add up. There will be a reckoning for Fleming if the government has to significantly increase taxes or run deficits to cover the teachers’ demands.

If Rob Fleming can avoid stumbling over trustee and teachers’ federation demands for more money, he will get a passing grade this year. If he can manage this while improving the funding model and addressing the teacher recruitment problem, Fleming can make the honour roll.

Jason Ellis, PhD, is an assistant professor in the faculty of education at the University of British Columbia.