When special investigator Beverley McLachlin passed the legislature-spending-scandal puck to the three house leaders last week, they had to do some stick-handling.

When special investigator Beverley McLachlin passed the legislature-spending-scandal puck to the three house leaders last week, they had to do some stick-handling.

Her report was dated May 3 and it took until May 16 before it was released. Over that period, the house leaders succeeded in changing clerk Craig James’s mind, no doubt with lawyers deeply involved. His determination to keep fighting to clear his name faded away and he decided to retire.

Mike Farnworth (NDP), Mary Polak (B.C. Liberals) and Sonia Furstenau (Greens) came up with an artful term to describe the parting of the ways.

It was a “non-financial settlement.”

It’s a fascinating term for a couple of reasons.

Just the idea of a “settlement” is curious.

McLachlin found misconduct on James’s part in several instances. Not only that, she emphatically rejected some of his explanations. One of them was incoherent, she said. On another, she said: “It is hard to understand what was going through Mr. James’s mind.”

Those dismissals are almost as damaging as the finding of misconduct, for someone in his position.

She found that he came up well short of what was expected of him, gave him every opportunity to explain himself, then completely dismissed his story.

Given that, what’s to settle?

The guy disgraced himself, so they could have fired him. But presumably there were several exchanges of views among lawyers that led to the settlement. It’s likely a reflection of how hard it is to simply fire senior executives who are entrenched in their positions.

That leads to the second curiosity — it’s a “non-financial” settlement.

The house leaders are keen to put this all behind them, so they won’t likely be offering seminars explaining what that means.

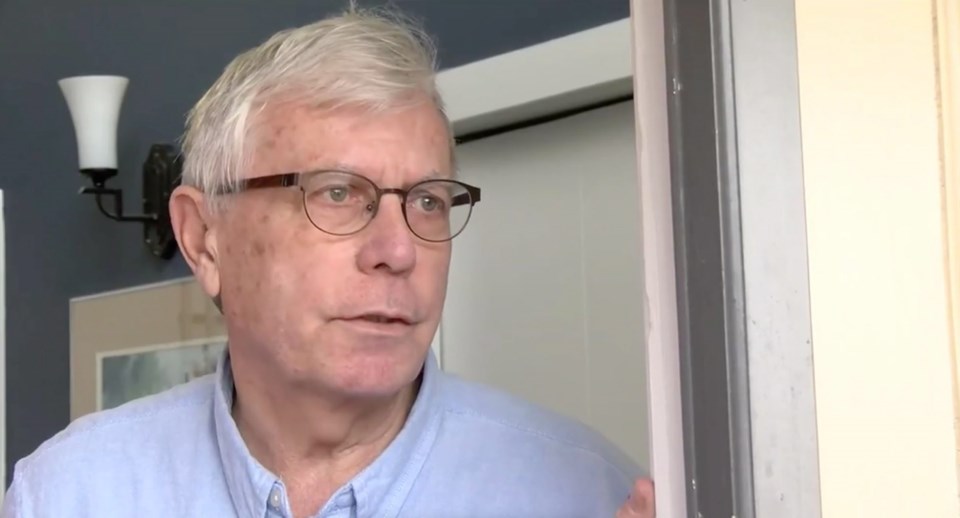

But Speaker Darryl Plecas, the whistleblower who started the controversy, shed some light in a weekend interview with Postmedia.

He wasn’t involved in the negotiations, but said the non-financial settlement goes both ways. Taxpayers won’t pay James anything to go away, beyond the pension to which he’s entitled. And he doesn’t have to pay back the value of the benefits he improperly obtained.

That leaves a lot of money in James’s hands that shouldn’t be there, judging by McLachlin’s findings.

Most of it involves retirement benefits.

James got a $258,000 retirement-benefit cheque in 2012 for some bewildering reason stemming from a benefit program that supposedly ended 25 years earlier.

He also got a signed letter from Plecas in 2017 that his estate would get $900,000 — about three times his salary — in the event of his demise while still working.

McLachlin found that agreement highly questionable, but said it might still be in effect.

Then there was an effort to get a year’s pay if he were to resign. McLachlin found James actively orchestrated the policy, “identified a lucrative benefit for himself and focused on getting it approved, rather than assessing it critically.”

It would amount to a future payout of $370,000 to him. Plecas signed on to it, but later rescinded it. McLachlin said it might not be in effect, but recommended that authorities monitor the legislature budget to see if any liabilities persist.

James also tried to claim for two years of life-insurance premiums from 2016-18, but it was partially denied because of the other benefits in place.

There is still the police investigation and auditor general’s probe to get through.

It’s not settled yet, and it doesn’t look to be “non-financial,” either.

Just So You Know: Deputy clerk Kate Ryan-Lloyd has been filling in since James’s suspension. She will likely succeed him permanently, and she thoroughly deserves the job, just based on one anecdote from McLachlin.

The former justice recounted the nonsensical history of the retirement benefit noted above that existed or didn’t exist, depending on who happened to be Speaker.

It produced a ludicrous situation several years ago in which the lump-sum benefit cheques magically appeared for some of the table officers. Ryan-Lloyd’s was for $119,000.

McLachlin said the deputy clerk was surprised and couldn’t understand the rationale for it, so “she returned the payment on the grounds she could see no basis for it.”