One of the lower-profile changes in the NDP’s legislative package is a bill that will move voting day in B.C. to October from May.

One of the lower-profile changes in the NDP’s legislative package is a bill that will move voting day in B.C. to October from May.

Whatever the B.C. Liberals do when it comes to a vote, in their heart of hearts, they probably welcome the change in the fixed date. After the experience this year, they probably wish they’d done it years ago. The last election provided a bizarre example of what can go wrong when a government goes to the polls before the books are fully confirmed.

The concern with holding elections in May, two months before the books are independently verified, was always that a government could present a picture of prosperity in a budget, only to have it dissolve after the votes were counted, when the fiscal scene is certified by the auditor general.

One of the many remarkable things about last May’s election is that almost the opposite happened. Liberals presented a modest surplus budget and campaigned cautiously. But they were overwhelmed after the vote by a huge, unexpected increase in the surplus estimate for the previous year. They couldn’t capitalize on it earlier because they didn’t know it was there, because the electoral and budget calendars didn’t mesh.

And as it turns out, the lack of interest in social spending is now being pinpointed by leadership candidates as a prime reason why they lost.

The good-news-bad-news story began in February with healthy but unspectacular budget numbers and a restrained plan to do little more than halve medical services plan premiums.

The party lost ground in the May election, and the NDP eventually enlisted the Greens to unseat the government. It was during that dickering that the Liberals realized they were in much better fiscal shape than first thought.

Then-premier Christy Clark started a blizzard of new spending to head off the NDP-Green alliance, but it was too late. All it did was arouse suspicions about a convenient 11th-hour jackpot.

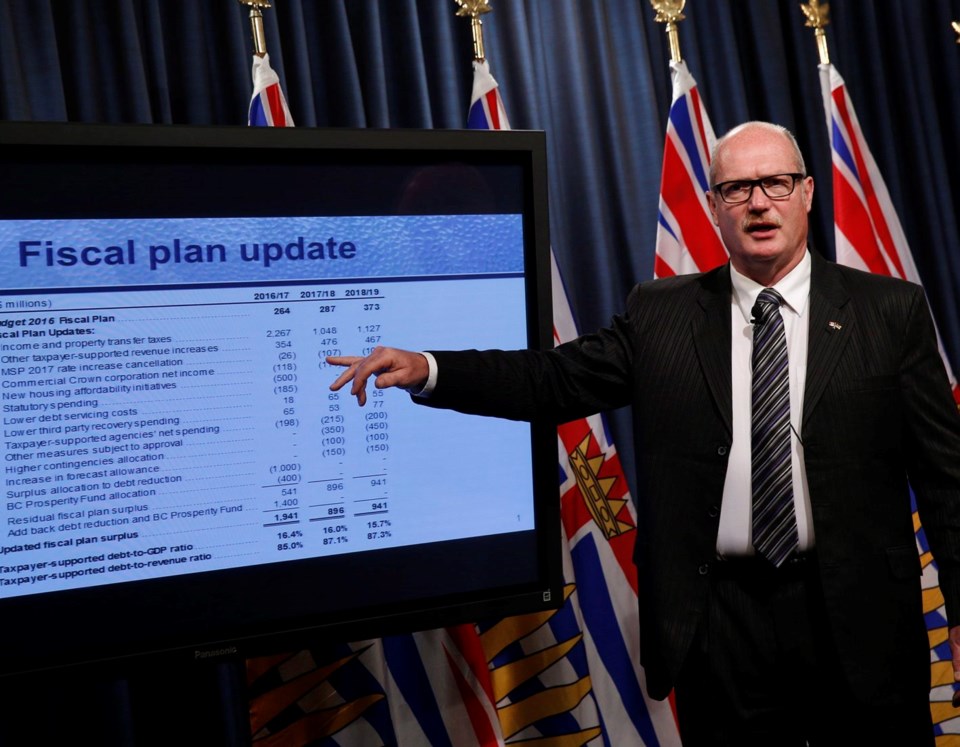

By August, the picture became clear. Their first estimate for the year ending last March was a $264-million surplus. It was later rose to $1.4 billion, but when the books closed it stood at $2.7 billion.

The B.C. Liberals were blindsided by their own good fortune. They engineered a bonanza at just the right point in the election cycle. But they didn’t realize they’d done it until it was too late.

Although Liberals are bitterly noting they “gave” the NDP $2.7 billion, it doesn’t carry forward. But it does confirm the Liberals could have done much more social spending in their last year in office than they did.

At the party’s first leadership debate on the weekend, some candidates acknowledged the perception their government didn’t direct enough spending to show they cared about people. Mike de Jong took some indirect hits for the misplay, because he was finance minister at the time. He acknowledged being called a “tightwad,” and said he’s the only (ex) finance minister in history to take heat for being too careful with taxpayers’ money.

But he conceded: “There were gaps. We could have made some other choices.”

Former cabinet minister Andrew Wilkinson said: “I would have liked to have seen at least half of that [surplus] go to things like schools in Surrey that we need so badly.” (The debate, which drew about 600, was in Surrey.)

“We had a huge surplus and we didn’t use it to invest in British Columbians. … It’s one thing we did that didn’t serve us well.

“If there’s a surplus, let’s deploy it for the benefit of British Columbians, and use it to help us win the election when we can.”

Others, such as ex-minister Todd Stone, admitted they fell short in standing up for the supports people need.

So now, they’re collectively talking about expensive new plans. Rapid transit to Langley. A major push on housing affordability. Annual education grants to kids. But it’s long past the point where it makes any difference.

Just So You Know: The Liberals set the fixed date for elections early in the first term, in 2001. The choices were fall or spring. They are rumoured to have picked spring after doing a study that showed governments get re-elected more often then than in the fall.