The B.C. Healthy Built Environment Alliance was established by the Provincial Health Services Authority in 2007 to provide leadership and action for healthier, more livable communities.

The key purpose of the alliance is to foster the partnership between urban planning and public health, which I wrote about last week. Members are drawn from the health, planning, non-governmental organization, municipal and academic sectors, as well as from ministries working in this area.

One of the problems with cross-disciplinary work such as this is that we all have our own language, so getting urban planners and public-health professionals to understand each other and recognize each other’s skills and areas of focus is key to taking joint action. Accordingly, one of the first things the alliance did was to organize “Planning 101” workshops for public-health professionals, so they could develop a better understanding of urban planning. This was followed by “Health 201,” a guide, toolkit and self-assessment tool for the design professions.

Ongoing discussions both at the alliance and through its network of members help keep this interaction and shared learning alive. This work is supported by the publication of case studies and best practices that highlight good examples across Canada of public health and urban planning collaborating alongside municipalities and communities to create healthier built environments.

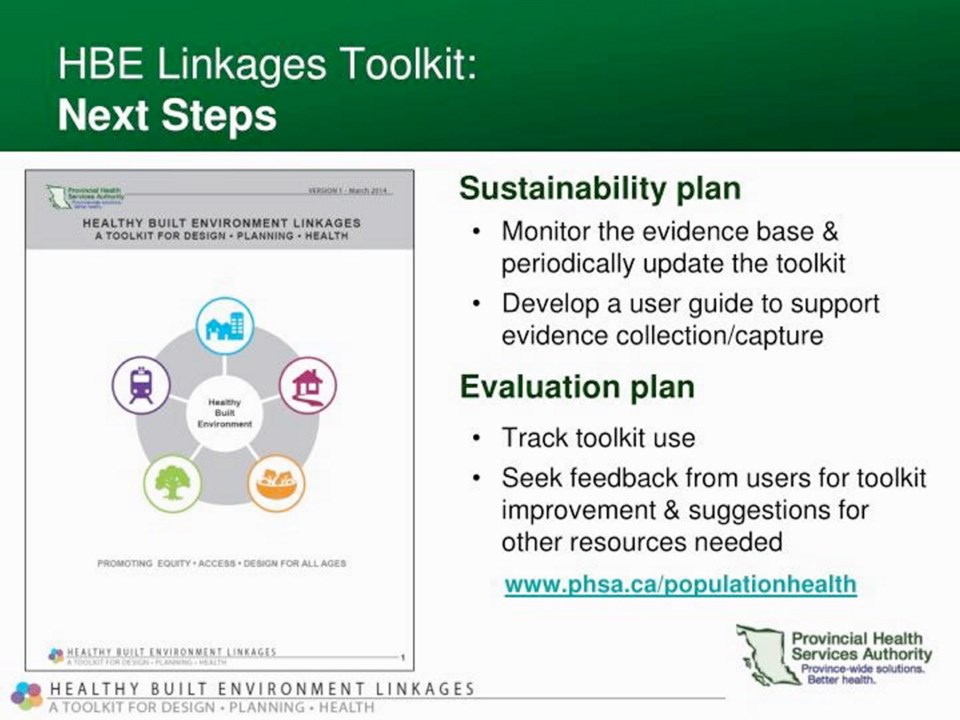

But one of the most important things the alliance has done has been to create a Healthy Built Environment Linkages Toolkit that makes clear the links among design, planning and health. While it is designed primarily for public-health professionals, its clear, simple design and graphics mean it can be used by anyone — including the development industry and the public — who is interested in creating healthier built environments (and it’s easy to find; just Google the title).

The toolkit is intended to provide all the participants in the planning process with evidence of the health implications of different aspects of planning and design. Its earlier version has been used by healthy-built-environment specialists in health authorities — yes, there are such beasts in some health authorities — and other public-health staff to work with local municipalities on official plans, helping them to consider the health impacts and benefits of their policies and planning decisions.

But there is no reason why the toolkit could not be used by community associations and other citizen groups to argue for better, more health-conscious planning decisions in their own neighbourhoods, or by private-sector planners and developers to create healthier communities that would be more attractive to potential purchasers.

The toolkit examines five key elements of the built environment that affect our health: Neighbourhood design, transportation networks, natural environments, food systems and housing. For each of them, the toolkit provides evidence of the key health benefits that can result from applying the principles and measures that are included. So what are some of the key features of healthy built environments?

The toolkit states that: “Healthy neighbourhood design is facilitated by land-use decisions which prioritize complete, compact and connected communities.” By “complete” they mean having a mix of residential, commercial, institutional and workplace sites so you can live, learn, work, shop and play largely in your own community.

These mixed-use neighbourhoods are also more compact, which makes it easier to meet the need for transportation networks that prioritize and support active transportation such as walking, biking and public transit. In fact, neighbourhood design and transportation — and indeed all the key components of healthy design — are complementary and often positively reinforce each other.

We can also achieve significant health and well-being impacts, the toolkit states, by preserving and connecting the surrounding natural environment; ensuring the “accessibility and affordability of healthy foods,” which “can be supported through land-use planning and design;” and developing quality, affordable housing options for everyone, especially including marginalized people.

Interestingly, many of these are also features of sustainable community design, reinforcing the principle that if we design for people and the planet, we are likely to build better communities — more pleasant, attractive and livable, as well as healthier and more sustainable.

Next week, I will delve in more detail into some of the key characteristics of healthy-community design.

Dr. Trevor Hancock is a retired professor and senior scholar at the University of Victoria’s School of Public Health and Social Policy.