When Capt. George Vancouver first came upon the island that would later be named after him, he wrote that it was “the most lovely country that can be imagined.” In The Land of Heart’s Delight, recently shortlisted for the 2014 City of Victoria Butler Book Prize, Victoria author Michael Layland provides the history on how and why Vancouver Island came to be mapped.

Early in March 1778, Capt. James Cook, Royal Navy, became the first Englishman since Francis Drake, two hundred years earlier, to see both coasts of North America. Cook, Britain’s foremost navigator and hydrographic surveyor, had developed his skills while preparing detailed charts of the St. Lawrence River for General Wolfe’s assault and capture of Quebec. Cook’s two-ship expedition, the third in his series of great voyages of scientific exploration, had been at sea for nearly two years.

Cook’s vessels, the sloops Resolution and Discovery, made landfall close to 45° north, the latitude the British Admiralty wrongly considered to be the northern limit of Spain’s imperial reach. Cook had been instructed not to provoke Spanish ire and risk Spain’s siding with the American revolutionaries. For the same reason, the names of both Resolution and Discovery had been changed — previously, they had been the Drake and the Raleigh respectively.

Cook had come to this coast on his way to find (or disprove the existence of) the western portal to the Northwest Passage. His orders required him “to proceed northward along the coast as far as latitude 65°, taking care not to lose any time in exploring [other] rivers and inlets, or upon any other account.”

Through fog and failing light, around latitude 48°15’, Cook sighted a headland but he needed to regain the safety of the open ocean. Bearing away, he noted beyond the headland, “a small opening in the land.” Already behind schedule, he had no time to investigate. Cook knew the story of Apóstolos Valerianos finding a strait at just this latitude but he ignored the possibility, naming the headland Cape Flattery. The small opening was probably not Juan de Fuca Strait, but Makah Bay, and the headland what is now called Point of the Arches, 15 kilometres south of today’s Cape Flattery, which marks the true entrance to the strait.

A further week passed before the expedition could make another landfall. They had continued to struggle north and, running perilously low on fresh water, approached what seemed, from a few leagues distant, to be a wide bay with two inlets. The southeastern limit of the bay was a headland with surf breaking over its rocky foot, which Cook called Point Breakers. This was the same perilous headland that Juan Pérez had, only four years earlier, named Punta San Estevan, and where he had just managed to escape a lee shore.

To the northwest, Cook noted another promontory that he called Woody Point. He was seeing the six-hundred-metre-high spine of the Brooks Peninsula. He chose “woody” for obvious reasons; however, a later hydrographer, George Richards, noting that the whole of this coast could be so described, renamed the feature at the western extremity of the peninsula Cape Cook, to commemorate its discoverer.

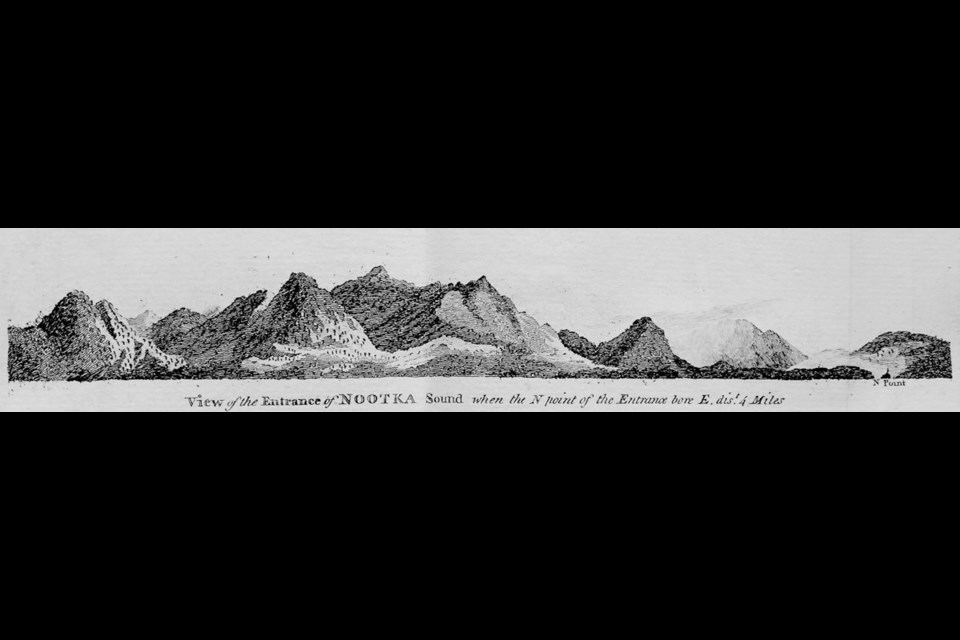

Approaching more closely, Cook saw, beyond the rocky shoreline, a land densely forested with a backdrop of rugged, snow-crowned peaks. Reflecting his optimism, he named it Hope Bay. On a light evening breeze they found an entrance, which Cook named King George’s Sound, after the monarch. As they arrived, a fleet of some thirty large canoes surrounded the visitors and greeted them with melodious chanting. Musicians on board returned the serenade on flutes and horns, to the evident appreciation of the residents.

Cook and his fellow officers watched the resident people gesticulate and call out “Noot’ka! Noot’ka ichim!” which they interpreted to be the local name of the place. In fact, the paddlers, familiar with the dangers of the exposed coast, had been instructing the ships to “come around, come around the point!” But thereafter, the name Nootka remained. The actual name for the Mowachaht summer encampment was Yuquot, meaning “exposed to the winds.” An additional European name was soon bestowed upon the same village, with good reason: Friendly Cove.

On the last day of March 1778, the ships dropped anchor in a small, sheltered bay in the middle of the sound, and parties went ashore. They were the first Europeans on record to set foot upon what became known as Vancouver Island.

The Mowachaht were eager, experienced and astute traders. All the sailors quickly learned another word: Makook? “Do you want to do business?” Scorning the glass beads and similar trade trinkets that the visitors first offered, the locals coveted any item of metal: knives, ships’ nails, brass buttons, tin cans and pewter plates.

In return, they could supply artifacts and animal pelts, particularly sea otter. For men about to face the rigours of the Arctic, this soft, rich, dense fur promised warmth and comfort. Not only would it make excellent clothing and bed covers, it seemed an attractive bargain. In all, the officers and crew of Resolution and Discovery carried away with them 1,500 sea otter pelts, little realizing what they had acquired.

While the vessels were laid up for refit, the expedition’s astronomer, William Bayly, determined the latitude and longitude of “Astronomer’s Rock,” the first accurately co-ordinated point on America’s west coast. Despite the instructions for Cook not to waste time charting the coast south of 65°, some of his officers took the opportunity to circumnavigate nearby Bligh’s Island in ships’ boats, and made their own sketch maps of the complex inlet. The two artists aboard, John Webber and William Ellis, also made good use of the time to observe and record the scenery, natural history, people, aboriginal dwellings and lifestyle, and artifacts. Their work provides an invaluable pictorial record of the Nootka region at the time of first contact by Europeans.

In his voyages of discovery, Cook established the model for how such missions should be undertaken and the findings collated, described and presented. He also trained a cohort of hydrographic surveyors to serve Britain’s expanding global maritime interests.

After exploring the coast of Alaska and into the Bering Sea, Cook decided to return to winter in the balmy Sandwich Isles, where he met his savage demise. The expedition continued after his death, going on to create, unexpectedly, the next stage of international interest in Vancouver Island. In Kamchatka, the crews met Russian fur merchants from whom they learned that the sea otter skins and other pelts that they had acquired in Nootka were valuable. The crews were pleased to sell them, but later, in China, they discovered that they had done so too cheaply.

As their exotic visitors departed, the Mowachaht returned, they probably thought, to the normality of nuh-chee, their land. The tranquil haven that had sheltered Resolution and Discovery for four weeks became, over the next decade, the busiest seaport on the west coast of the Americas.

Cook’s expedition returned to England in October 1780. Four years later, and after two unauthorized accounts of the voyage had appeared, the official, three-volume version of Cook’s journal, A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean for Making Discoveries in the Northern Hemisphere, edited by Lt. James King, was published. That same year, Cook’s chief cartographer, Lt. Henry Rogers, issued an accompanying atlas of charts of the third voyage. His Chart of the NW Coast of America and the NE Coast of Asia includes detail of the coastline at the expedition’s landfall, then at Cape Flattery, and again at Hope Bay, Nootka and Woody Point. The chart shows their track well offshore between these points and northwestward until they reached Alaska. The supposed coastline between the identified locations is indicated by a dotted line. This was the first published chart showing data from actual observation of any part of Vancouver Island.

Excerpted from The Land of Heart’s Delight: Early Maps and Charts of Vancouver Island, TouchWood Editions © 2013 Michael Layland.