This is the last in the Tales from the Vault series of columns in which Stephen Ruttan, history librarian of the Greater Victoria Public Library, explores the history of Victoria. The library will be publishing a well-illustrated collection of all the Tales from the Vault that have appeared on its website. The tentative publication date will be March 2013. Anyone interested in purchasing this book should send an expression of interest to [email protected]

In the early 1990s, several groups of Mowachaht elders left their homes on Vancouver Island and travelled to New York. They had been invited by the American Museum of Natural History to see a mysterious object that had left their community 90 years ago.

This object, the Yuquot Whalers’ Shrine, is composed of an original small building and its contents: 88 carved human figures, four carved whales and 16 human skulls. It was collected in 1904 by George Hunt, acting on the instructions of a museum curator, Franz Boas. The shrine had been built over several generations by Mowachaht ancestors, but few living band members had seen it. The question hanging over the elders was this: Should the shrine come back home? But an outsider might well ask another question: Why is it in New York at all?

The American Museum has an enormous northwest native art collection, the largest in the world. And New York is not alone. Museums throughout the world have substantial collections of this art.

European collection of native artifacts was, until the mid-19th century, mostly sporadic. They were not seen as art, but more in demand as fascinating curios. In the late 1850s, this started to change.

In 1886, a young German named Franz Boas got a long-awaited chance to go to the northwest coast in hopes of collecting for New York museums. He arrived in Victoria in September, and spent the autumn visiting native villages. He learned a great deal, and collected many artifacts. When he left the coast, he went to New York, where he tried to get a job at the American Museum of Natural History. He had no luck, but did get a job as an editor at Science magazine.

Boas impressed Frederic Ward Putnam, the most prominent American anthropologist. When the American Museum hired Putnam as head of anthropology he was determined to hire Boas, who joined the staff in 1895.

The German developed a bold new plan for the museum. He decided that a major anthropological expedition was needed to northwest North America and northeast Siberia. The idea was to send many scientists into the field over a six- or seven-year period. Boas would pick the people, and direct their research.

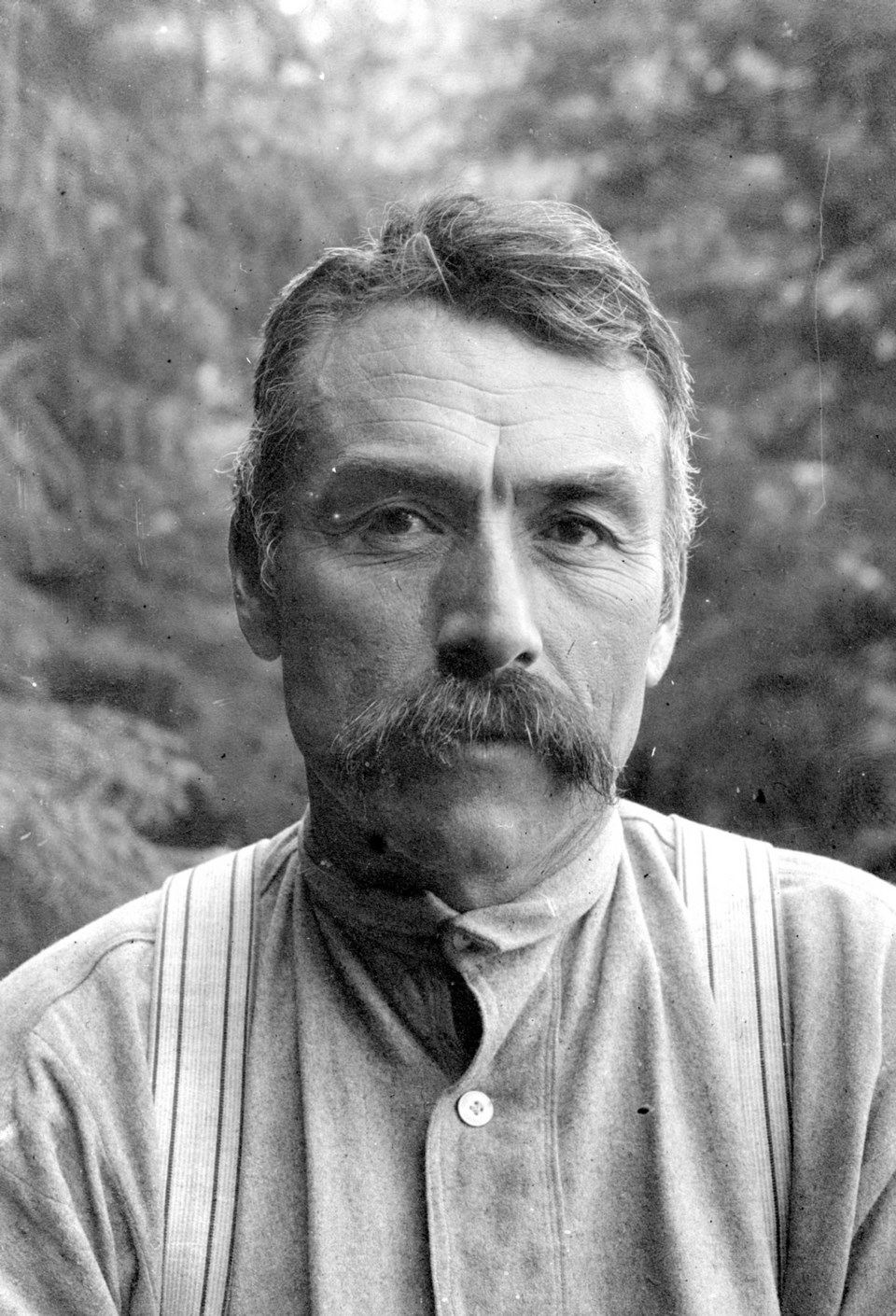

A major part of this expedition was to exhaustively collect among the northwest native people. Boas wanted both artifacts and information. He needed the right person, and luckily he found him. On a trip to the northwest coast in 1888, Boas had met a Kwakiutl man, George Hunt. The son of a Scottish trader and a Tlingit noblewoman, Hunt had grown up in the village of Fort Rupert. He was a full member of the Kwakiutl community and had inside access to information. He was also bilingual.

After some initial ethnographic training, Hunt got to work. Over the next few years he more than proved his worth. A large number of excellent items streamed to New York.

Talking with some Nootka in 1902, he heard about a whalers’ shrine. Intrigued, he travelled the next year to see it, but he was rebuffed. The Nootka owners insisted on proper spiritual credentials. Hunt said he was a shaman, and proved it by curing a man. So the owners gave him access. With the time available he took one quick photograph.

That photograph changed everything. Boas was fascinated, and it is easy to see why. Even today it is a haunting picture. In the photograph, your view is partially blocked by bushes. Peering over them, you are looking into the dim light of a wooden shed. A few rays of sun brighten the scene. Rows of strange, human-like figures line the shed. These figures have no arms, and all have different expressions. At their feet is a row of skulls. A larger skull, on the right side, is shining in mid-air. A few of the figures, caught by the sun, shine out of the gloom. The whole scene is utterly strange and mysterious. It was like nothing Boas had ever seen.

Adding to the mystery is the secrecy that has always surrounded the shrine. Hunt recorded some information in 1904. But it took him nearly 20 years to find more. The problem was that few tribe members knew very much and when they did, they were unwilling to talk. The shrine was the property of the chief whaler, and only he could use it. Other tribe members were not even supposed to mention its existence. So Hunt could find few good informants.

What he did discover was that it was used in purification ceremonies before a hunt. The whaler needed to remove his scent, and absorb the power of his ancestors. One ritual, for example, involved strapping the mummy of his father to his back, then clutching a carved whale, and plunging into a nearby lake. Another was beating his skin raw with branches, then plunging again into the lake. The whaler would spend several days in the shrine. The skulls and the human-like figures undoubtedly added to its power.

Boas knew he must have this shrine. A note of insistence crept into his letters, as he urged Hunt to get it. But Hunt was facing trouble. By 1904 he had much easier access to the shrine. Now, though, two people were claiming ownership, and each insisted he had the exclusive right to sell. Hunt was able to bring these two together, and strike a deal. Even so, it could not leave the community immediately. The owners said it must stay until the tribe departed for the sealing season. They feared an angry backlash.

By the end of 1904 the shrine was dismantled, and shipped to New York. And Hunt was well pleased. In his letter to Boas he said: “It was the best thing I ever bought from the Indians.” But it proved a strange victory. A few months after this, Boas resigned from the American Museum. He became a full-time university professor. With Boas’s departure Hunt became far less active as a collector.

After the shrine arrived in New York it disappeared from view. It was Boas’s project, and with him gone no one cared to make a display of it. A few pieces have been in exhibits over the years. But mostly it has been a century of storage.

Meanwhile, the fortunes of native people have been reviving in Canada. The tribal groups have become determined to recapture their cultural heritage. This includes the Mowachaht people, the heirs to the Whalers’ Shrine.

In 1983, the Mowachaht began to consider a cultural centre, one that would include the Whalers’ Shrine. Museums were coming under pressure to return art and artifacts to their original native owners. In 1990, two other communities, Alert Bay and Cape Mudge, had their artifacts returned. With this in mind, the Mowachaht elders set off for New York.

Seeing the shrine was a powerful experience for them. But it left them divided. There were those who said it should come home, that it would revitalize the community. Others were not so sure. One said, “I don’t want to see it on display — it’s just too sacred.” Another said, “You don’t tamper with things you don’t understand .... You don’t tamper with the Whalers’ Shrine.” For them the power still held.

The band as a whole, though, came to a decision. In November 1996 it voted to formally request the shrine’s return. It also began planning a cultural centre at Yuquot, where the shrine and the band’s history could be displayed. Here things have temporarily stalled. But the momentum is there, and one day the centre will be built.

The only remaining question is, will the shrine ever be open to the public? That would have been unthinkable in the 19th century. But as times change so does the meaning of the shrine. Once it was restricted to the chief whaler. Now all band members may see it. And in the future all of us may be included.