The universe of mutual funds today has grown from years of popularity. This popularity is the result of mutual funds being the most convenient option.

Perhaps the biggest criticisms we hear about mutual funds are the costs to hold them. Other criticisms we hear is with respect to performance — or underperformance.

The Canadian Securities Administrator (CSA) has implemented new rules requiring financial institutions to provide better transparency with respect to both costs and performance.

Costs and performance really are linked to some degree. One analysis we do for individuals considering the transition from mutual funds is to look at our managed account option which holds individual positions with no embedded fees. With a managed account, a Portfolio Manager and yourself, agree to a set fee.

It is easy for us to analyze a basket of mutual funds to determine what the ongoing embedded costs are, often referred to as a Management Expense Ratio (MER). We realize that it is not as easy for others without the tools to do this same analysis. Below we will provide an example of the large cost savings using both registered accounts and non-registered accounts.

Registered accounts

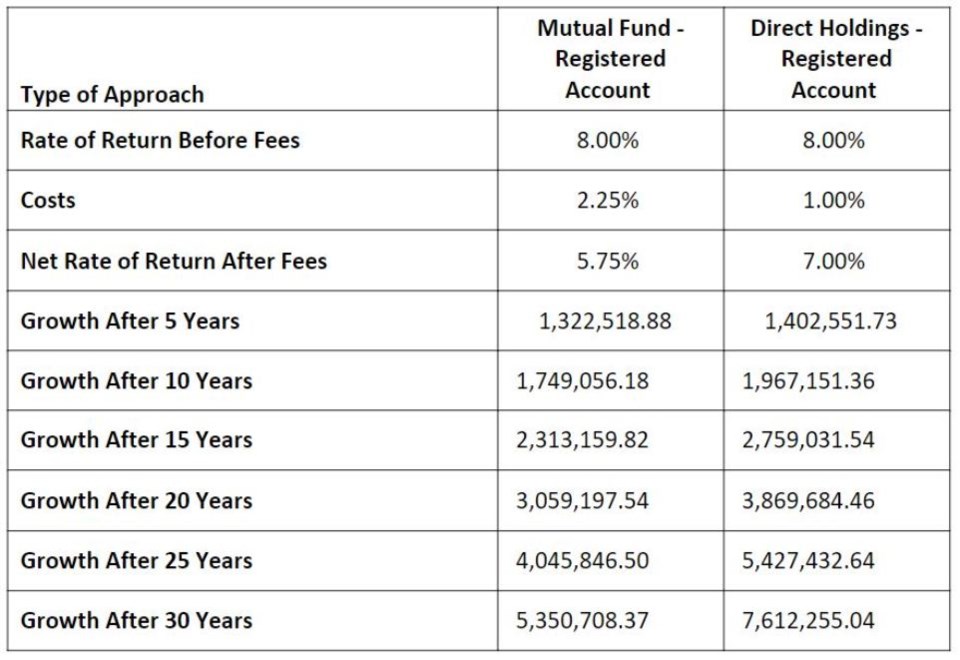

Mr. and Mrs. Smith both have Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs). Combined they have $1 million invested in mutual funds. With registered plans, the analysis is straightforward. We first look at the Management Expense Ratio (MER) of the underlying funds.

The Smiths’ mutual funds have an average MER of 2.25 per cent. We presented the option to Mr. and Mrs. Smith of having all direct holdings with no embedded fees. We explained to them that the annual fee would be 1.00 per cent.

When stated as a percentage, it does not give the true impact of how important 1.25 percentage point savings is. Let’s look at this in dollars and cents of both approaches.

The Smiths are currently paying, on a $1-million portfolio, $22,500 every year in MER fees — these are embedded within the mutual funds, which they cannot see.

We explained to the Smiths that with the managed fee-based account, the fees would drop to 1.00 per cent, or $10,000 (which they will see/is transparent), assuming the same $1-million portfolio.

Every single year, the Smiths could save $12,500 by transitioning out of mutual funds to direct holdings within a fee-based account.

Growth of $1 million in a registered portfolio over time (net of fees)

Below is a table assuming an annual rate of return of eight per cent before costs.

Non-registered accounts

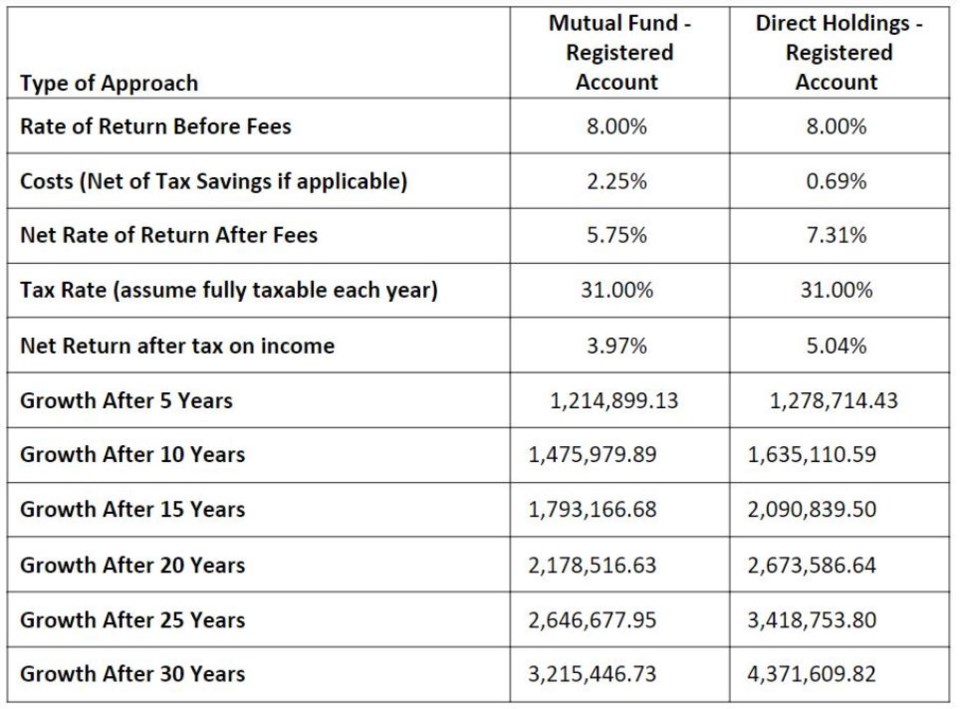

Mr. and Mrs. Jones have invested $1 million in mutual funds within a Joint Tenancy with Rights of Survivorship (JTWROS) non-registered account. They are invested in mutuals funds that have embedded MERs. The average MER of 2.25 per cent equates to annual embedded fees of $22,500, like the Smiths above.

Mr. and Mrs. Jones are each in the 31 per cent tax bracket. We explained to Mr. and Mrs. Jones that because the fees within the mutual funds are embedded, they are not able to claim the MER as a deduction. We explained to Mr. and Mrs. Jones that our managed account fee is considered an investment council fee and is tax deductible for non-registered accounts. We explained that the managed account fee of 1.00 per cent, or $10,000, can be deducted on their personal income tax return.

As Mr. and Mrs. Jones are in the 31 per cent tax bracket, they will save $3,100 in taxes. The net fee that Mr. and Mrs. Jones will pay is $6,900. In the first year, the Jones could save $15,600 ($22,500-$6,900) by transitioning out of mutual funds to direct holdings within a fee-based account. Every year after that the savings would be even higher.

Growth of $1 million in a non-registered portfolio over time (net of fees)

Below is a table assuming an annual rate of return of eight per cent of fully taxable income.

Compounded savings over time

The above illustrations show the savings over time for both Mr. and Mrs. Smith and Mr. and Mrs. Jones assuming an eight per cent rate of return, before fees, and before taxes. The analysis is for a five-, 10-, 15-, 20-, 25- and 30-year time period. The compounded savings are substantial.

Additional benefits

There are many benefits, outside of reduced fees, of holding a direct investment (i.e. a single stock). The above analysis assumes eight per cent fully taxable income each year. If the eight per cent were a mixture of deferred growth, capital gains, and dividend income the end results would be substantially higher.

From a portfolio analysis standpoint, it is easier to control types of income, placement of investments, geographical exposure, sector exposure, and asset mix. When you hold an investment directly you also have more control over the tax situation of the investments.

For example, you could hold a stock for 30 years and not pay any tax on the gain until you sell it. Like Warren Buffet, some holdings are worth holding onto for a long time and deferring tax on the capital gain until it is sold years later or deemed to be sold on death.

With a mutual fund you have no control on the tax slip you receive at the end of every tax year. Choosing to concentrate on core names also helps improve performance in our opinion.

Kevin Greenard CPA CA FMA CFP CIM is a Portfolio Manager and Senior Wealth Advisor, Wealth Management with The Greenard Group at Scotia Wealth Management in Victoria. His column appears every week at timescolonist.com. Call 250-389-2138, email [email protected] or visit greenardgroup.com.