A baby boom is coming to J-Pod.

The endangered southern resident killer whales, down to 74 animals in three pods, could use the infusion of new life, but scientists and observers are cautiously optimistic: Baby booms during 2015 and 2016 produced six calves, but only two have survived.

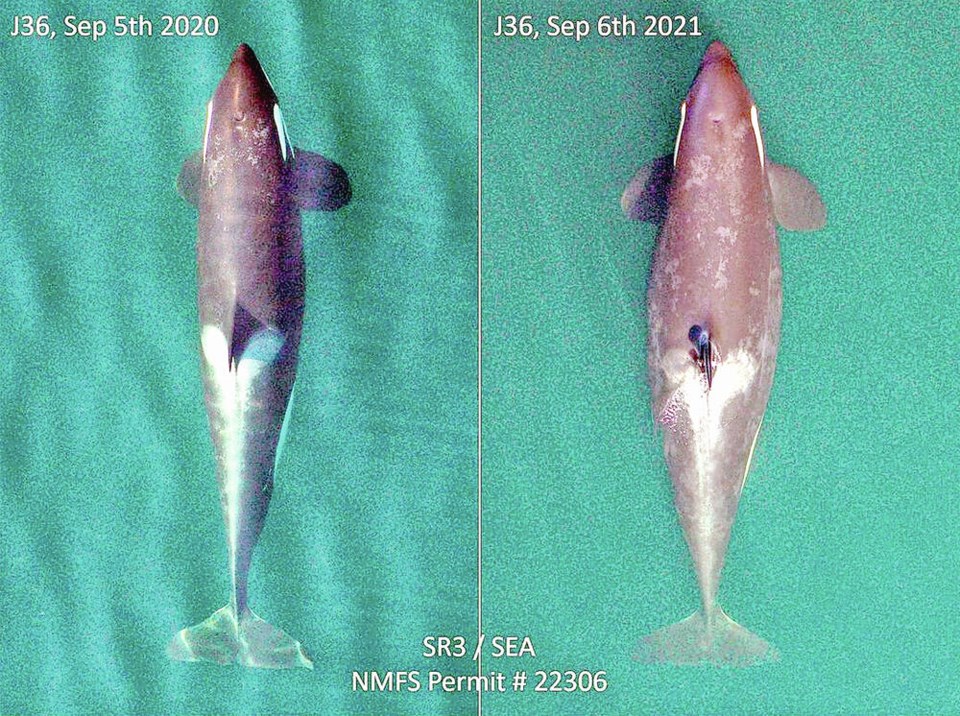

Drone footage captured by scientists at Sealife Response, Rehabilitation and Research, a Washington-based non-profit, indicate that J36, J37 and J19 are in various states of pregnancy. There is no specific timeline on the births. Orcas have an 18-month gestation period.

Young orcas have about a 50-50 chance of survival, said Dawn Noren, a biologist with the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration based in Seattle.

She said the southern resident population faces many challenges, including dwindling stocks of chinook salmon, their chief food source, toxins in the water and food, and increasing boat noise.

Several members of J-Pod have recently been reported in the Strait of Georgia around Vancouver, foraging for salmon returning to the Fraser River.

Orca mothers increase their food consumption by 25 per cent during pregnancy and then double it after giving birth to produce milk for their calves, Noren said. With salmon in increasingly short supply, she said, mothers have to work extra hard to forage for food, often amid boat noise that affects their echolocation, which is how they find fish.

Noren has done studies on orcas in aquarium settings that show orcas’ milk is contaminated with PCBs from fish they are fed. In the wild, it’s likely higher — and those toxins are passed to the calf, potentially creating serious health issues that reduce the chances of survival.

The three pregnant whales have all calved before, but not for several years, Noren said.

Between them, there have been five births — and only two offspring have survived.

According to the Orca Network, which tracks the southern residents, 44 orcas have been born and survived since 1998. Over the same period, 80 have gone missing or have been confirmed dead.

J19, known as Shachi, is the second-oldest member of J-Pod. She’s 42 years old and has given birth twice before. Her first, a male known as J29, survived only a few weeks. But her second, J41, or Eclipse, born in 2005, has given birth twice, and J19 has helped raise both calves.

J36, or Alki, is 22 and has given birth only once, in 2015. The calf, J52, or Sonic, died six months later, shortly after weaning.

J37, also known as Hy’Shqa, is 20. She had male calves in 2012 and 2015 — J49 (T’ilen I’nges), who is still part of J-Pod, and J55 (Betel), who died.

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans is enforcing a 400-metre distance between all vessels and orcas until at least May, and all whale-watching companies have signed an agreement not to watch the southern residents and to focus on Bigg’s orcas. In the U.S., vessels must stay 275 metres away.

Erin Gless, executive director of the Pacific Whale Watch Association, said the rules are not being followed by other vessels, including many recreational boaters.

“While our whale-watch vessels are keeping a distance, we are still observing from afar a lot of other vessels exhibiting fast and dangerous boating behavior near southern residents with very little enforcement presence,” Gless said. “Requests for extra space from whale watchers doesn’t do much if other vessels aren’t required to also oblige.”

Scott Rumsey, deputy regional administrator for the U.S. Department of Fisheries, said everyone needs to work together “to give these pregnant whales every chance of success. The more they can forage undisturbed, the better their odds of contributing to the population.”