Radiologists are the latest group of specialists to ring alarm bells with the province about long waiting lists.

An estimated one million patients are waiting to see a specialist in B.C., including hundreds of thousands waiting for medical imaging, according to a Sept. 26 letter from the B.C. Radiology Society to Health Minister Adrian Dix, shared with the Times Colonist this week.

“We fear for the tsunami of cancer cases — including those initially detected at stage II and above — that may be coming in B.C. because of delayed access to medical imaging,” says the letter from society president Dr. Charlotte Yong-Hing.

The letter came on the heels of a Sept. 21 open letter to Dix signed by 26 specialists, and supported by hundreds, asking the province to take urgent action as “patients are getting sicker and dying on our waitlists.”

The specialists pointed to a “crisis” in wait times in all specialities, from cardiology to dermatology, neurology and oncology, citing examples of patients on the Lower Mainland and on Vancouver Island with “new cancer diagnoses waiting 2-3 months for their first visit with an oncologist.”

Doctors of B.C. said it shares the specialists’ concerns. “Patients who wait — sometimes years — for specialist care often see their conditions worsen while being in unbearable pain,” president Ramneek Dosanjh said in a statement.

Dosanjh called the situation “unacceptable” and said doctors are facing “huge moral distress” because they are unable to help.

During a media availability on Wednesday, Dix said there has been a spike in demand for diagnostic testing and response to testing, including for cancer, and “we’re working hard to meet that.” We’re facing a challenge now, absolutely, and it’s our goal to address that in the midst of many, many challenges of demand … that are meeting the health care system,” he said.

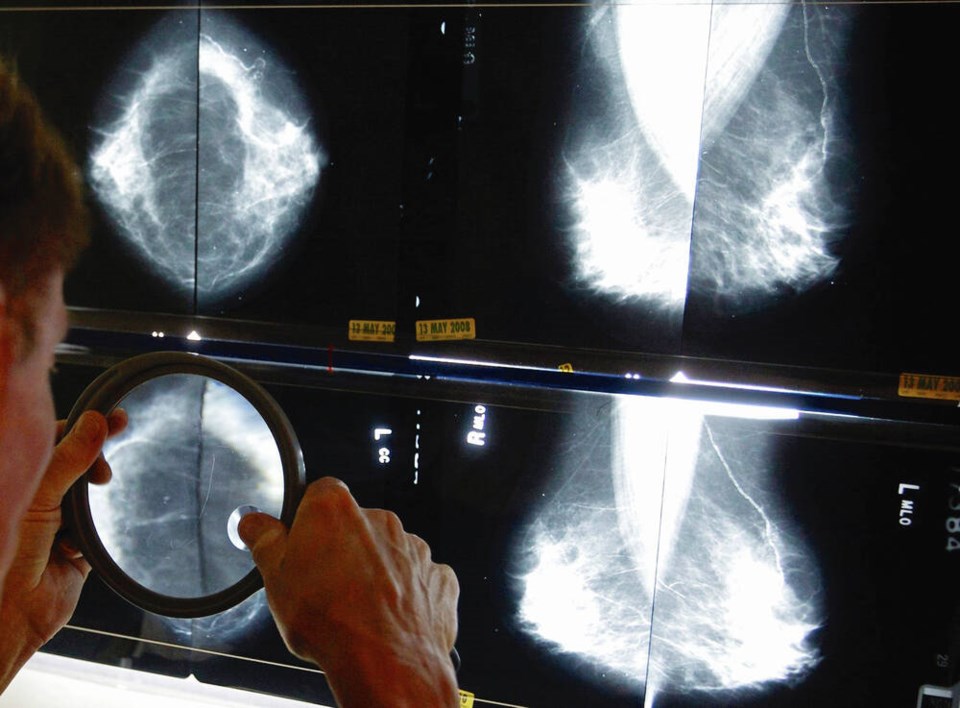

In her letter, Yong-Hing cites wait times for breast biopsies and supplemental imaging such as digital breast tomosynthesis — 3D mammography — for patients with higher risks, including dense breasts and family history.

Tomosynthesis technology, which can detect cancer earlier, has become the standard of care at most imaging sites across Canada, she said, but a new fee code for tomosynthesis has been with the Health Ministry for over two years with no action.

The codes would provide clinics monetary compensation for each exam, and help to recoup operating costs, maintenance and replacement of technology.

Bob Rauscher, CEO of the B.C. Radiology Society, said the province’s use of tomosynthesis software is “sporadic” in the absence of sustainable capital planning and budgets for technology.

“Foundations in B.C. remain the primary source for capital funding — that’s problematic,” he said.

Delays in medical imaging can lead to delays in diagnoses, specialist referrals, surgeries, medical treatments, and cancer care.

The B.C. Radiology Society is asking the province to address four key areas, including a shortage of medical imaging technologists, “outdated” equipment, extra imaging for patients at higher risk of breast cancer, and keeping open community imaging clinics that are at threat of closure.

Yong-Hing applauded the province for recent investments in MRI and CT scans.

On Wednesday Dix noted a “significant increase” in positron emission tomography/computed tomography scanners in the cancer system. In 2019-2020, two PET/CT suites were added, one at B.C. Cancer Centre in Victoria and the other in Kelowna. Together they produce about 5,000 scans a year.

However, Yong-Hing said there is significant need for new equipment: “The current approach of relying on foundations for medical imaging equipment funding is not working.”

Community imaging clinics — privately owned clinics that provide publicly funded services — are struggling with overhead costs and are under the same threat of closing as family-doctor practices, she said.

The imaging clinics provide about one million imaging studies annually, including at least 60 per cent of all breast imaging, and are funded on a fee-per-exam basis.

The clinics are responsible for purchasing and servicing medical imaging equipment and paying for technologists, administrative staff and lease costs.

If some clinics are forced to close, “it would have a catastrophic impact on medical imaging wait times,” said Yong-Hing, since the diagnostic tests would fall to the acute-care system.

Rauscher said while training new radiologists and creating sustainable capital plans for equipment are longer-term strategies, new fee codes for breast imaging technologies such as tomosynthesis and support for community imaging clinics are easy problems to fix.

In response to the letter, the Health Ministry issued a statement saying the province has added 17 “net-new” MRI units across B.C. since August 2017, including four in the Island Health region, which has reduced wait-times for diagnostic imaging in B.C.

For MRI wait times, B.C. improved from fifth in the country in 2018 to second best in 2021, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, a ministry spokesperson said.

For CT wait times, B.C. improved from sixth in the country in 2018 to third in 2021, according to CIHI.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]