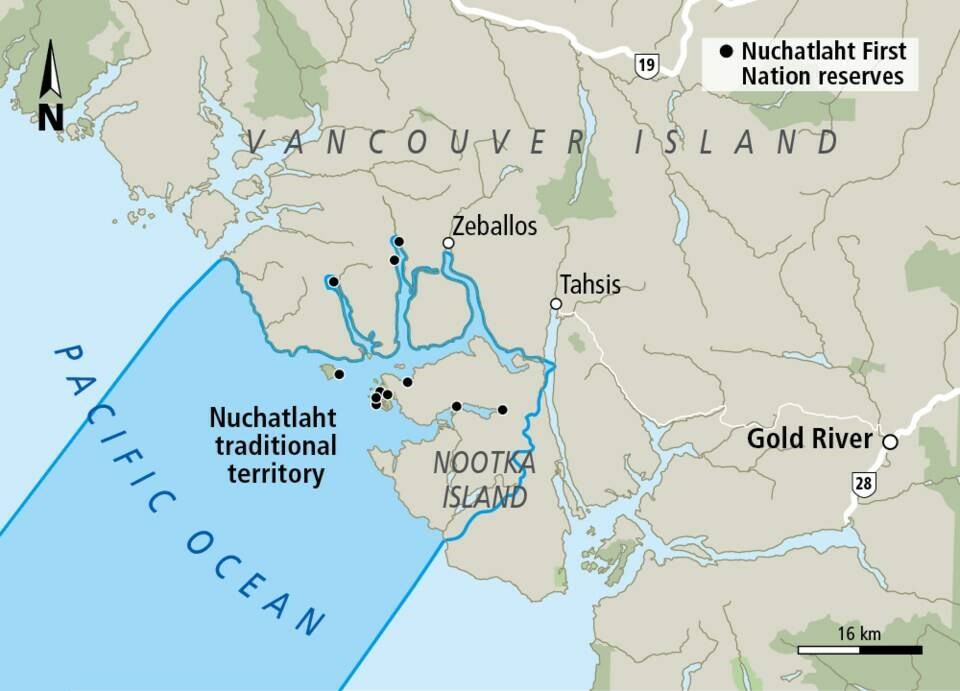

The Nuchatlaht First Nation on Vancouver Island’s west coast has appealed a B.C. Supreme Court decision that recognized the nation’s Aboriginal title to only part of its traditional territory on Nootka Island.

In April, B.C. Supreme Court Justice Elliott Myers recognized the Nuchatlaht’s Aboriginal title to about 11 square kilometres on the northwestern part of Nootka Island.

Myers had previously rejected the nation’s claim to a much larger area, about 200 square kilometres, of Crown land covering a portion of Nootka Island and much of the surrounding coastline, saying the nation had not proved its claim to the overall area.

The decisions followed a 54-day trial that started in March 2022 after the nation brought the claim in 2017.

“We have been fighting for our rights since my great-grandfather told the Indian Agent to stop giving away our land over 100 years ago,” Chief Jordan Michael said in a statement. “We have been determined for over a century. This is only a partial victory. We are not going to stop now.”

The nation originally went to court because it wants to restore the land, which has been poorly managed, said Archie Little, a Nuchatlaht elder and councillor.

More than 80 per cent of old-growth forests have been cleared in the region and no watersheds are intact, the nation has said. They want to rehabilitate the ecosystem, including strengthening wild salmon populations, while supporting its people and culture.

“The legal system has to understand the truth is that we owned, we managed, we enhanced, we protected [the land], and we shared, and we were wealthy. We want to get back to that way of managing, because we’re running out of resources,” Little said.

The nation has the authority to decide what to do with the portion of land where its title was recognized, which it called “a disjointed territory with arbitrary and unnatural boundaries,” and to benefit economically from its use. The land’s value has been estimated at between $28 million and $280 million.

Work is in progress to develop laws and policies to manage the land sustainably and to assert ownership, Little said.

“We need to show the world how First Nations managed, looked after and respected Mother Earth, and we need to get back to that,” he said.

The ruling in April that recognized Nuchatlaht’s Aboriginal title to some of its claim area marked the first time a B.C. court had recognized a First Nation’s Aboriginal title.

A previous land-title decision in favour of the Tsilhqot’in First Nation in central B.C. was won in the Supreme Court of Canada after an appeal.

“I do think it was substantial,” said Owen Stewart, a lawyer representing Nuchatlaht.

But he said it was surprising that most of the claim area was rejected, with the province arguing that mountains are too remote and the forests are too thick for Nuchatlaht to have ownership — given the agreement the province made with the Council of the Haida Nation in April.

That agreement acknowledged Haida Aboriginal title over all of Haida Gwaii, an “enormous land mass” 48 times larger than the Nuchatlaht claim area with “high mountains and deep inland regions,” Stewart said.

“It seems odd to me,” he said.

Stewart anticipates the appeal will be heard in late 2025.