And finally, just in time for Christmas — or maybe New Year’s — Jennifer Lannan will get the present for which she has been waiting five long years: her husband.

The 31-year-old Saltspring Island woman, her 36-year-old Nigerian spouse and their son will, at last, get to begin life together as a family now that immigration authorities have agreed to let him into Canada.

In the end, it shows what can happen when persistence, common sense and compassion are allowed to prevail.

Their story has been well documented. They wed in 2008 in South Korea, where Lannan was teaching English and Johnson Emekoba ran an export business.

Lannan then returned to Canada to begin the process of bringing her husband here. It took until May 2009 for her application to sponsor him to be approved, and another year for Canada’s immigration office in Ghana, where the region’s applications are processed, to look at the file.

The train seemed to be on track when they reunited in the West African country for an interview in May 2010, even after they disclosed that Emekoba had played fast and loose with the documents that let him stay in South Korea.

In fact, officials were so encouraging that the couple felt safe beginning a family. Lannan became pregnant.

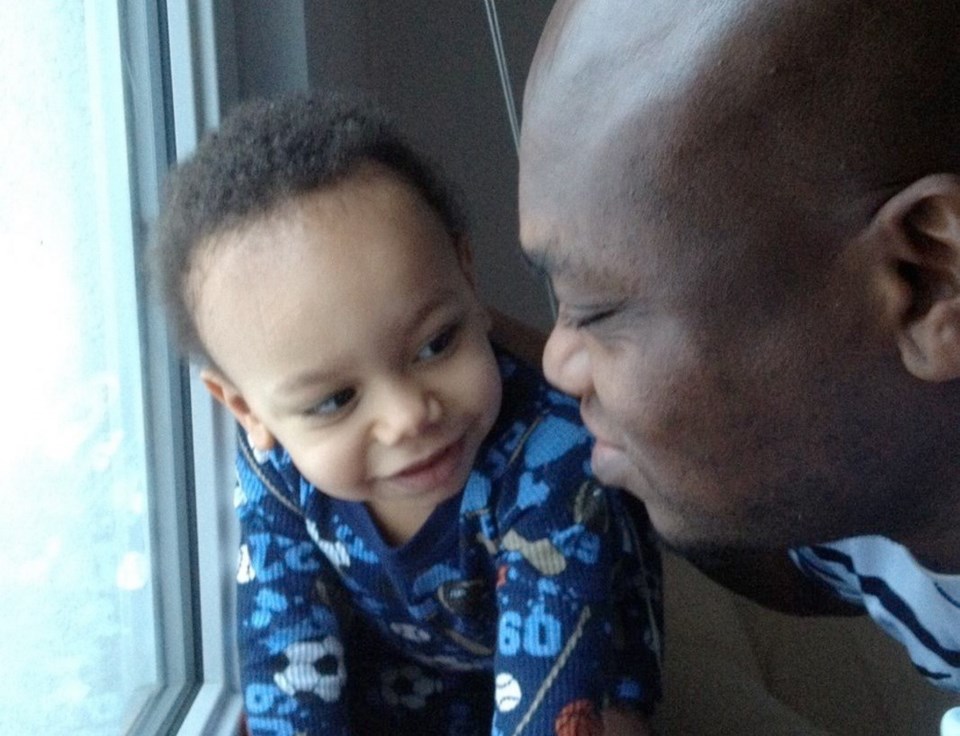

Alas, when baby Gerard Emekoba was born in Saltspring’s Lady Minto Hospital in February 2011, Emekoba was still in Nigeria, stranded by a never-ending bureaucratic process: Questions asked, answered, asked again as letters were lost, the communications punctuated by long silences.

The file was among the first to land in Elizabeth May’s lap when she was elected Saanich-Gulf Islands MP that spring. When Emekoba was ruled inadmissible to Canada, May helped engineer a successful appeal in 2012, the immigration minister agreeing it would be better for the baby to grow up in a stable, two-parent family.

Even then Emekoba was stuck, as the slow-motion ping-pong continued. More letters were sent and lost. Forms grew outdated. The big problem was South Korea doesn’t do the kind of criminal record check demanded by Canada’s visa office in Ghana. There was still no end in sight when the young family was briefly reunited in Poland last Boxing Day.

The couple didn’t give up. Neither did May, who recently began rising early to get on the phone to Ghana. The MP conscripted Canada’s new immigration minister, too. “Chris Alexander has been really helpful,” she said Friday.

On Tuesday, she phoned Lannan with news that the visa office was, at last, reasonably satisfied that due diligence had been done. Emekoba was cleared for permanent residency.

“I lost it,” Lannan says.

Now it’s all happening quickly. Emekoba will set out from Nigeria on Monday for a Wednesday appointment to pick up his papers in Ghana. He could arrive in Canada by next weekend. If not, it will be the weekend after that.

Lannan, having fought so long to be with her husband, suddenly faces the details of married life. “This morning, I was worrying about the closet.” She has to make room for his clothes.

The family has stayed connected via iPhones and Skype — “We talk a few times a day. There are not many days when we don’t talk” — but life with father will still be new for Gerard, who turns three in February. “He’s so excited. He needs his dad.”

Lannan, who first went to an immigration lawyer five years ago this week, acknowledges nearing the end of her rope. “I was getting really, really not OK.” She has had enough of life as a single mom, looks forward not only to being together as a family, but having a bit of time by herself — going to the gym, say.

She is grateful to May and her staff, but worries about others caught up in an immigration process that has been overwhelmed. Every member of Parliament has a stack of immigration files. In September, the government said the citizenship application backlog had been reduced to 349,249 cases by the end of last year — though this was achieved in part by simply throwing out more than a quarter of a million applications that had been languishing for four years or more. The average processing time was 25 months for a routine application and 35 months for a more complicated one.